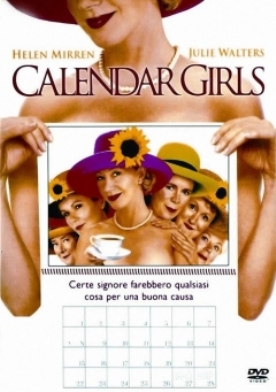

Calendar Girls

It is an interesting coincidence that Nigel Cole’s Calendar Girls should have had its premiere in the same month that Playboy is celebrating its 50th anniversary. The female nudity on display in the magazine for the last half century is hardly more remarkable nowadays than the “cheesecake” pinups of the World War II era, but its lasting legacy is on display in the movies. This is in our readiness to associate public déshabille, or the willingness particularly of women to appear in same, with authenticity — and to confer upon those who indulge in it the boon of celebrity.

The film tells the now-familiar story of the respectable middle-aged ladies of the Women’s Institute of Rylstone (here called Knapely), in West Yorkshire who got their kit off for charity and then became world-famous. Its assumptions are thus similar to those of another film set in the north of England, The Full Monty, but with the addition of a certain amount of feminist self-congratulation. When, for instance, prissy Marie (Geraldine James), the president of the chapter who had opposed the nude calendar, sees what a success it is, she takes up the cry that it shows how the WI is “about education and empowerment of women; not just jam and ‘Jerusalem’, you know.”

The problem with the film is that it has no interest in exploring these curious ideas of “empowerment” and personal authenticity arising out of public nudity but simply assumes them — expecting us to do the same. It insists on behaving as if its subject were a story about the ladies when in fact it is a story about our society. The result is that although it is not infrequently charming, it quickly bogs down in soap opera.

Will this woman or that woman throw in her lot with the strippers, or with Marie? Will Chris (Helen Mirren), who organizes the calendar, be spoiled by success? Will Annie (Julie Walters) get over her grief after the death of her husband (John Alderton) from cancer? Will Ruth (Penelope Wilton) manage to hold her marriage together or win a new independence and self-confidence?

If these kinds of questions matter to you — and if you don’t already know the answers to them — you might enjoy the movie, but there seems nothing very extraordinary about the high concept of ordinary women stripping for the camera. And the piquancy of their doing so is a wasting asset. A recent report that the librarians of the London borough of Camden have produced a similar calendar has not so far produced the call from Jay Leno that came to the Rylstone nudes. For once such a bastion of middle-class respectability as the WI has fallen, there are precious few categories of women left who could make news just by showing off their assets. Nuns or clergy-persons could, or politicians. Certainly militant feminists. But that’s about all I can think of.

Even when the newly media-savvy “girls” fly to Hollywood to appear on Leno’s “Tonight Show,” both they and the film-makers determinedly ignore the much more interesting subject of the popular culture which thrives on the manufacture of new celebrities — often, as in their case, with the most trivial of claims upon the public attention. This celebrity culture insists on demonstrations of humanity which cut through the mystique of honor, respectability, dignity, reticence, and decorum.

Such qualities are now regarded as old-fashioned and kicked away with contempt as phony, while their opposites become signifiers of authenticity and are imagined to be the route to female “empowerment.” More and more, celebrity creation is accomplished by some such public humiliation, as on the TV “reality” shows. If that’s not more worrying to us than the tale of the calendar girls is heart-warming, then we are far-gone indeed in decadence.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.