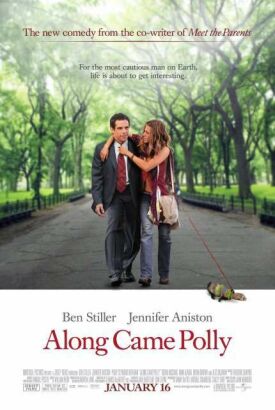

Along Came Polly

First the good news about Along Came Polly, written and directed by John Hamburg. In parts it is very funny. True, a lot of the humor depends on thunderous borborygmus and torrential bodily extromissions, which may seem simply gross to those of finer sensitivities. Presumably Mr. Hamburg, who co-wrote the screenplay of that earlier and funnier Ben Stiller comedy, Meet the Parents, was responsible for that movie’s scatological elements.

Mr Stiller as Reuben Feffer, risk assessment manager of an insurance company run by Alec Baldwin is also the principal asset of this movie. He may not have an enormous range as an actor, but what he does — which is to portray a small but likeable man in ecstasies of embarrassment — he does very well indeed. Philip Seymour Hoffman, by contrast, who plays his best friend in Polly, seems to have a bad case of the great-actorism that has for so long afflicted his namesake, Dustin. I find him pitiably unfunny. This is all the more to be regretted because he has no other function in the picture except to be funny.

In fact, that is the function of everything in it — which means that, like so many movies nowadays, it can be appreciated as a sort of stand-up routine: one gag after another, sometimes loosely strung together and sometimes not, but without any larger coherence. At best, Along Came Polly is two movies. In the first, Reuben is abandoned on his Caribbean honeymoon when his wife, Lisa (Debra Messing), takes up with a French nudist and scuba-diver (Hank Azaria). This seems to have nothing much to do with his being who he is — that is a fussy, nerdy risk-assessor who brings his work home with him — but only with the fact that Lisa suddenly discovers she is not, as they say, ready for “commitment.”

This first movie only lasts for about 15 minutes. The second, in which Reuben’s character does become highly relevant, begins when he takes up with the eponymous Polly (Jennifer Aniston) two weeks later on the rebound. Polly is a friend from the Model UN in which both participated in middle school and a free-spirit, but she is even more averse to “commitment” than Lisa is. Miss Aniston is cute as always but does nothing here to dispel the impression of vacuousness that such cuteness tends to convey. She has traveled the world, writes unpublishable children’s books, keeps a blind ferret named Rodolfo and is fond of Latin dancing and exotic ethnic foods, but all these things never quite add up to a whole character. Instead she is a mere schematic of Reuben’s opposite.

So then it’s a movie about opposites attracting? No, not really. In the end, Reuben discovers that that “safe conventional guy” that everyone thought he was is “not who I really am.” Polly, he thinks, has liberated him from the childhood constraint of an over-protective mother (Michele Lee) to become a risk-taker like herself — though oddly he becomes, also like her, more rather than less averse to the risk of commitment. This, I’m afraid, is where the movie’s theory (such as it is) falls down. For Mr Stiller has done far too good a job being Reuben up to this point to persuade us at the last minute that he was really somebody else all along. Thus the attempt to create a dramatic context for the jokes, some human explanation of why the people we are watching are doing the things they are doing, founders on the jokes themselves, or at least the best of them.

Nor does it help that a half-hearted attempt to account for the change, not only in him but also in Mr Hoffman’s character, by an inspirational speech from Reuben’s father (Bob Dishy), who is otherwise silent, is couched in vulgar psychobabble — “It’s not about all this etc. etc. . .You have to enjoy the ride etc etc.” Such banalities hardly amount to life-changing insight, which is apparently how we are meant to take them. But you may enjoy the ride anyway, just for the laughs.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.