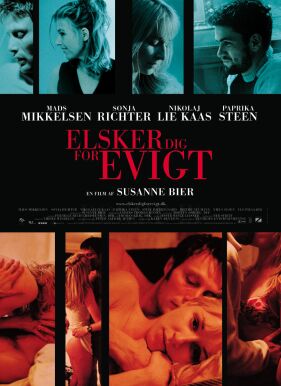

My Top Ten Movies of 2003

The New York SunTo my mind, the best film of 2003 by a long way was Susanne Bier’s Open Hearts, a typically generic, market-tested title for a generic, market-tested Hollywood picture but wildly inappropriate for Miss Bier’s deliberately under-produced, Dogme 95 film. The Danish title, Elsker dig for Evigt, or “Love you forever,” gives a much better idea of the terrible ironies she and Anders Thomas Jensen (Mifune, The King is Alive), with whom she co-wrote the screenplay, are dealing in.

It is a movie about a man’s life-altering injury and the guilt it induces in those around him — especially his fiancée, who finds she can’t stand by him even if she wants to. The subtlety and wisdom of the writing and the breathtaking, pitch-perfect acting are beautifully set-off by the simplicity of the production values, which is what the Dogme 95 credo always, I take it, intended to do but never did better than this. Unfortunately the film has not been issued in a video or DVD form.

As for the rest of the Top Ten, since none stands out above the rest I’ll merely list them in alphabetical order.

The French-Canadian Denys Arcand’s Barbarian Invasions is the sequel, 15 years later, to his Decline of the American Empire and is, like it, a a funny and intelligent commentary on our times. Though its perspective is left-wing, the film is much more self-critical than you would expect from an American director with comparable views. The last days of Rémy (Rémy Girard), a dying professor of politics, are carefully arranged for him by his ex-wife (Dorothée Berryman) and estranged son, (Stéphane Rousseau), and the family’s reconciliation encourages him to look back on both his life and his radicalism with a fitting regret but without, somehow, undue melancholy.

Michael Winterbottom’s In this World is a quasi-documentary about two Afghan boys who set out from a refugee camp in Pakistan for London, half a world away, where a life of drudgery (as it must seem to us) represents the promised land to them. The film’s political perspective is simplistic, but this turns out to be weirdly appropriate to the story of two children whose difficult lives have not afforded them the luxury of any politics at all. Their dumb sufferings are at times almost unbearable, but so is the poignancy and beauty of their hope.

The Coen brothers’ Intolerable Cruelty I found, as I find most of their movies, brilliant, clever, funny and heartless. But as it is a kind of updated screwball comedy about a divorce lawyer (George Clooney) and a gold-digging femme fatale (Catherine Zeta-Jones), its heartlessness actually makes a kind of sense and doesn’t become obtrusive. At any rate it leaves us free to appreciate the comedy, the brilliance of the dialogue and plotting and the enormous attractiveness of the principal actors.

Peter Weir’s Master and Commander is a visual treat as well as a thrilling action picture which, amazingly, most fans of Patrick O’Brian’s novels seem to like as well. In spite of one or two anachronistic touches and what I thought the distracting theme of scientific progress, what must have been the physical reality of life on board a man-of-war in the Napoleonic era is more than hinted at, while Russell Crowe makes a persuasively heroic Captain Jack Aubrey.

Out of Time

by Carl Franklin is an old fashioned thriller in the noir-style, but it manages to be much more sunny and unaffected than most recent attempts by Hollywood —— to recapture the noirish effects of 50 or 60 years ago. In a contemporary context or a self-consciously “period” recreation (L.A. Confidential comes to mind) these generally come across as mere nihilism. Not so the story of Denzel Washington’s immensely likeable Sheriff Matt Whitlock, who recaptures something of the innocence of the genuine noir hero and whose loneliness is for once not just a pose.

The new version of Peter Pan by P.J. Hogan (Muriel’s Wedding) is the best cinematic representation there has ever been of the boy who wouldn’t grow up — played, for once, by a real boy (Jeremy Sumpter) — and, more to the point, of Wendy (Rachel Hurd-Wood), John and Michael. The three Darling children return to the moral center of the drama, where J.M. Barrie first put them a hundred years ago, and we have the sense of seeing an over-familiar story for the first time.

The Safety of Objects

by Rose Troche and based on stories by A.M. Homes is too busy to hang together properly as a single film. Our emotional attention is divided between too many different stories. But all of the stories, considered by themselves, are sharply observed and often poignant. And the acting — especially that by Glenn Close, Dermott Mulroney, Moira Kelly, Mary Kay Place, Patricia Clarkson and several younger performers — is terrific.

After Farewell My Concubine and The Emperor and the Assassin, Chen Kaige’s Together looks like an unashamed appeal to popular sentiment, but movies were invented for the sake of popular sentiment. This tale of a 13-year old violin prodigy (Tang Yun) from the Chinese provinces and his relationship with his father, a simple peasant (Liu Peiqi) who gives up everything for his son’s career, is sentiment in the good old Hollywood style that you hardly see anymore from Hollywood.

Finally, Winged Migration by Jacques Cluzaud, Michel Debats and Jacques Perrin is not only beautiful in itself but a reminder of what a gloriously visual medium film can be. The birds here shown in flight as they have never been seen before except by other birds will stay with you for a long time. Their images and the promise of natural beauty and innocence that they imply might even sustain you through another year of Hollywood’s fashionable cynicism and schlock commercialism.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.