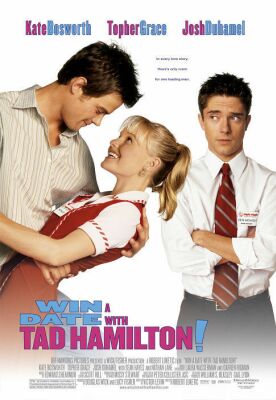

Win a Date With Tad Hamilton

The time-tested formula in Win a Date with Tad Hamilton, directed by Robert Luketic and written by Victor Levin has an innocent, wholesome middle-American youth suddenly translated to the cynical, amoral, unreal city and, instead of being corrupted by it, influences it for the better. Kate Bosworth plays Rosalee Futch, a supermarket checker from Frazier’s Bottom, West Virginia. Kate wins a contest whose first prize is a date with Hollywood heart-throb Tad Hamilton (Josh Duhamel). Oddly, though she works in a supermarket she seems not to have seen the supermarket tabloid in which Tad’s latest “bad-boy” antics are retailed — which antics are the reason for the contest in the first place. To her he is as good and noble as the characters he plays in the movies.

Yeah, right. Somehow I doubt that the Fraziers Bottoms of America will be flattered to see their youth depicted as being so clueless. On their date, even Tad is taken aback by Rosalee’s innocence, and he pursues her to West Virginia, telling her that he doesn’t want romance but only the friendship of such a good person. He hopes some of her purity and innocence will rub off on him. “She has a goodness and there’s a lot that I can learn from her,” he tells his predatory agent, Richard Levy (Nathan Lane). “I want to feed my soul.”

Even more unbelievable than Rosalee’s innocence is the fact that Tad actually seems to mean this, at least at first. So then all it takes is one date with this naVve hick chick from the sticks who throws up in his limo and won’t sleep with him and suddenly Mr Teen Idol is on a spiritual quest? That’s asking us to believe just a Tad too much. But the movie has already moved on to presenting us with the too-unbelievable-to-be-funny competition between Tad and Pete (Topher Grace), the local boy who loves Rosalee but is too shy to tell her,

All this is pretty silly, but silliest of all is the pretense that there is still a pristine and innocent part of America so untouched by the ways of Hollywood as to appear to the jaded metropolitan eye an Eden of innocence and wholesomeness. “Your values are different,” says the agent: “She has them.” But we see little reason for believing this apart from Rosalee’s natural desire for her boyfriend to be sincere. For the most part, their values are indistinguishable. That leaves the notional goodness of Frazier’s Bottom expressing itself like Pete, who tells Rosalee as she leaves for Hollywood to “guard your carnal treasure.” Who speaks like that today? This vision of Middle America looks even more unreal than Hollywood.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.