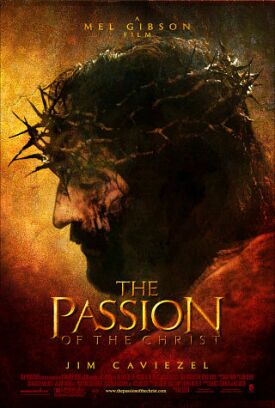

Passion of the Christ, The

Up until about the 13th century, the iconography of the Crucifixion, so far as we can tell from the artefacts that have come down to us, did not stress the sufferings of Christ on the cross. The stylized renderings of the Passion (as they must seem to us) presented Jesus as a young hero — one who could certainly have come down from the cross if he had chosen — unscarred and undaunted. The Florentine artist, Giotto (c. 1267-1337), is generally credited as being the first to break with this tradition and present a more realistic Christ. After him, “three nail” artists won out over “four nail” ones. In the gospels it doesn’t tell us how many nails were used to affix the Lord to the cross, but the earliest artists always showed four nails, one for each hand and foot. The 13th century avant garde introduced their striking and innovative suffering Christ with both feet impaled by a single iron spike — because it would help accentuate His agonies.

And so began the long, empathetic tradition of Western art which has continued, with a break for the abstract period early in the last century, right down to — Mel Gibson. Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ is the ultimate example of the style which Giotto began. It is also the ultimate in our great contemporary tradition of victim chic. Gibson’s Jesus (James Caviezel) is presented not as godhead but as victimhood incarnate. Nobody — not Marlon Brando in The Chase, not Sylvester Stallone in Rocky, not Denzel Washington in Glory, not even Mel himself in Braveheart is going to take a more impressive beating than Jim’s Jesus does. But without any more of a context than they are given here, his sufferings are merely bewildering, sickening. Surely, whatever other heterodoxy he may be guilty of, Mel cannot believe that pity is the same thing as piety?

This Jesus suffers ostentatiously from the moment of his first appearance on screen, which is when he is praying in a spookily-lit Garden of Gethsamane after the Last Supper. Even there he looks as if he is suffering from acute indigestion. Then, from the moment of his capture by the temple servants, led by Judas (Luca Lionello), he is almost continually beaten, cuffed, punched, kicked, slapped, whipped, gouged and pushed until he finally expires on the cross looking like an ill-prepared and half-cooked Christmas ham. The Resurrection is reduced to a 30-second coda. An almost entirely mute appearance by two of the three Marys — Maia Morgenstern as the Mother of the Lord and Monica Bellucci as the Magdalen — and John the Evangelist (Hristo Jivkov) has no other function than to accentuate the pity still further, as we see his sufferings reflected in their compassionate faces.

The accusations of anti-Semitism which have done so much to keep this film in the news for nearly a year before its opening stem, I take it, from this tremendous thrashing that precedes the actual crucifixion. They are to some extent a bum rap. Gibson does not seem to me to go out of his way to stress the Jewishness of the Jewish priests and Pharisees such as Annas (Toni Bertorelli) and Caiaphas (Mattia Sbragia), nor of the Jerusalem mob chanting “Crucify him!” My admittedly unpractised eye caught no stereotypes. The Roman soldiers — a brutal and undisciplined rabble motivated by nothing but sadism — come off worse than anybody. At the same time, Mel Gibson must have known that, in taking torture and brutality as his subject in preference to more traditionally spiritual considerations, he ensured that not only those who were implicated in such a crime but also those with a history of being unfairly implicated in it would feel themselves aggrieved. My guess is that he’s not sorry to have stirred up this hornet’s nest.

At any rate, it takes our minds off what’s really wrong with the movie. I have the most tremendous admiration for Pope John Paul II, but if he really said on seeing the film as he was at first reported to have said (before an official spokesman denied it) that “It is as it was” then I don’t think much of him as a movie critic. The one thing we can be absolutely sure of is that it is as it wasn’t. For although much publicity has been given to the fact that the screenplay is in Aramaic, the language of Jesus, and Latin, the language of the Roman imperial authorities, much less well known is the fact that it is also in a third language and that is Movieish, the language of the long line of cinematic sufferers that have come before this Jesus and that cannot but distract us from a proper consideration of what is, after all, meant to be a unique event in human history.

Nor is it only the scourging and beating which is written in Hollywoodese. Allusions to other movies range from Chuckie-like child sprites out of mainstream horror flicks to a pale Bergmanian devil with a dramatically gratuitous snake to certify his scriptural authenticity. There is even at one point a computer-animated movie demon like something out of The Devil’s Advocate or The Ninth Gate. This kind of thing I found at least as dislocating to the sense of occasion as if, instead of Latin and Aramaic, the movie had been made in Brooklynese. All of which is simply to say that The Passion of the Christ is like every other Mel Gibson picture in being ridiculously overproduced. As the British would say, he has once again over-egged the pudding. The new age music with pan pipes and wordless choruses, the swelling orchestral sounds at moments of significance, the flashbacks cross cut with the main action so as to produce heavy-handed ironies — all these things take us annoyingly out of the period and plonk us down jarringly in the entertainment culture of the present day.

Dramatically, too, the mise-en-scPne is pure Hollywood. In Braveheart, the Scottish patriot William Wallace (played by Mr Gibson) is depicted as going to war with the English because his fiancée is executed by them for resisting an attempted rape by an English soldier. In The Patriot, the American patriot Benjamin Martin (also played by Mr Gibson) is depicted as going to war with the British because a very wicked British colonel murders one of his children and orders another to be hanged. Obviously, in Mel Gibson’s world, nothing big ever happens without the most lurid and shocking sorts of evil to react against. But we have it on the authority of our own experience that the kinds of evil Christ was sent into the world to react against were for the most part much more familiar and mundane. Mind you, I understand why he felt he had to hype it. He’s making a movie, after all, and a movie — especially one made by a Hollywood star — is always going to look like a movie. But how much more interesting it would have been if Mel Gibson had restrained himself a bit and tried, instead of going with the Hollywood fashions, some pre-Giotto style serenity.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.