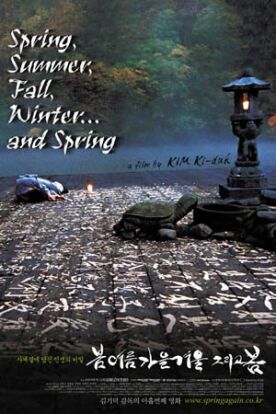

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter. . .And Spring (Bom yeoreum gaeul gyeoul geurigo bom)

Buddhist film must be at some level a contradiction in terms. Film depends on movement — that’s why they call them movies — where Buddhism prizes stasis and stillness. The Korean picture Bom yeoreum gaeul gyeoul geurigo bom or Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring, written and directed by Ki-duk Kim, manages to create a pleasing compromise between movement and stasis. It tells its story, or stories, in five separate segments corresponding to the seasons of the title. This suggests concentration of time to go with the concentration of place — all segments are set in a wooden monastery built on an island in the middle of a beautiful sylvan lake — even though the apparently consecutive seasons take place in widely separated years.

In the monastery there are only two inhabitants: an nameless old monk (Yeong-su Oh) and a young boy (Jong-ho Kim), whom he is presumably training. In the first spring, the boy torments a fish, a frog and a snake by tying a stone to each. The old monk scolds him, telling him to free the animals — and “if any of them is dead, you will carry the stone in your heart for the rest of your life.” Two of the three die, but the consequence for the boy is deferred.

In the “Summer” segment, a woman brings her ailing daughter (Yeo-jin Ha) to the monk to be healed. The boy, now a teenager (Jae-kyeong Seo) is smitten with the girl. The old monk warns him that “lust awakens the desire to possess; and that the intent to murder,” but he runs off with the girl, taking the old monk’s statue of the Buddha — and a chicken — with him.

In the “Autumn” segment the old monk comes to the monastery from somewhere else with a cat in a bag. He sees a newspaper with a smudged photo and the headline: “Man, 30, flees after murdering his wife.” Naturally, after what he said to the boy at the end of the previous segment, we expect it will be the same boy, and, sure enough, soon there comes a young man (Young-min Kim) who is obviously desperate and full of guilt and grief. His wife had gone with another man, he says. How could she have done that? “Did you not know how the world of men is?” Says the old monk. “Sometimes you have to let go of the things you like. . .What you like, others will like too.”

But this is not the same young man who went off with the girl in “Summer” — or if it is he has changed out of all recognition. The old monk just says to him: “You have grown a lot.” The young man attempts to commit suicide, and the old man stops him. “Young fool!” he says as he beats him. Though the old monk gives him sanctuary for a time, the young man is pursued and captured by two detectives. When they take him away, the old monk goes through the same pre-suicide ritual as the youth, gets in the rowboat that is his link to the world and immolates himself.

In “Winter” a woman (Ji-a Park) brings her baby to the monastery where another young monk, played by the director, Mr. Kim, now lives alone. She falls through the ice on the lake, leaving the monk to look after her baby. He ties a millstone around his waist and climbs to the top of the nearby mountain, carrying the now-returned Buddha from the second segment, so doing penance for the sin of the boy in the first segment.

In the second “Spring” which ends the picture we see another boy playing, this one tormenting a tortoise, as the Buddha looks on from the mountain top.

The film is remarkable for seemingly telling the story of one life — in one year — while actually telling several. The young monk in all his different incarnations is played by different actors. One runs off with a girl, another one comes back, carrying the same buddha (or is it a different one?) that the previous one took away with him, having killed his wife. He is taken away to prison and a third young man comes back as if he had been the one to leave. Or is he the first one finally returned? At any rate, he does the penance that the first one had deserved as a child and is then transformed into the old monk when another child comes.

“‘Tis all one,” say Shakespeare’s characters when, wearied with their very Western ambitions and strivings they dismiss a proposal for more strife. This movie makes the same point, conjuring an image of simplicity and unity out of an immense diversity of experience like a rabbit out of a hat. Not of the Buddhist persuasion myself, I nevertheless admire the aplomb with which the trick has been performed as well as the beauty of the natural setting.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.