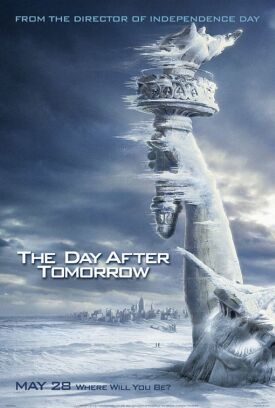

Day After Tomorrow, The

Opening the week after Michael Moore’s anti-Bush rant Fahrenheit 9/11 won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, Roland Emmerich’s The Day After Tomorrow is yet another reminder, if one were needed, of the liberal to radical sympathies of most of those who work in Hollywood. Also like Moore’s movie, it expects its politics to be taken as an earnest of its artistry. If all artists are left-wing, then all left-wingery — so the reasoning goes — must be art. In fact, The Day After Tomorrow is just a cheesy disaster movie whose overlay of politically-motivated environmental concern is meant to supply a veneer of sophistication. Transparent as as this is, it is even less successful at concealing the fact that, like so much of environmentalism, it is really anti-Americanism in disguise.

As in all disaster movies, a lonely but right and righteous scientist tries to make the complacent towns-people — here represented by the inhabitants of Planet Earth — listen to his predictions of doom. And when they don’t, masses of them come to a nasty end. “See? I told you so!” the smug scientist says on behalf of his equally smug creators. “You wouldn’t listen to me, and now you see what it has cost you.” Unlovely as this attitude is, it is altogether familiar to those who watch such movies, perhaps for the vicarious thrill of identifying themselves with the unappreciated prophets in which they specialize.

“The whole damn [ice] shelf is breaking off, that’s what’s happening!” says this movie’s lone sane man, climatologist Jack Hall (Dennis Quaid).

“Professor Hall, I think your theory may be correct,” says the pretty girl.

His theory, by the way, is that global-warming is melting the polar ice caps, thereby filling the oceans with fresh water and stopping their warm-water currents cold, so producing a new ice age. But even Jack doesn’t know that it’s all going to happen in less than a week.

“My son is there!” he says when, in Washington, he realizes that New York is about to be slammed by a tsunami and then blast-frozen.

“The wolves are gone!” say the shocked keepers at the Bronx Zoo.

“I love you,” says Jack’s ex-wife (Sela Ward).

“You can’t make it to New York, Jack!” says his more timid boss.

“I’ve walked that far before in the snow,” he replies.

“I’ve been watching your back for 20 years; I’m not going to let you go alone,” says the doomed old sidekick (Jay O. Sanders).

“Me neither!” says the cute young sidekick (Dash Mihok)

See what I mean? Familiar. The well-worn conventions of the disaster movie prove to be a lot more sturdy than New York skyscrapers and somehow make it seem less important that even Emmerich’s fellow environmental fanatics and Kyoto-boosters have acknowledged that the film’s scenario is scientific nonsense.

Yet the science-fantasy is less important to the German-born Emmerich than the anti-American fantasy, in which the global super-power is humbled, its few inhabitants who remain unfrozen painfully making their way to Mexico — which then proceeds to close its borders to the riff-raff from el Norte. How sweet it is! As in his previous films, Independence Day and Godzilla, Emmerich also gets a big charge out of portraying the destruction of American national icons — the White House and the Chrysler Building in the earlier films, the “Hollywood” sign and the Statue of Liberty here. Nor is he shy about tying it all up with present-day politics. The villain of the movie is a sinister Vice President (Kenneth Welsh) made up to look like Dick Cheney. And even though the President (Perry King) looks a lot more like Al Gore than George W. Bush, when disaster strikes he turns, nervously, to his vice president and says: “What do you think we should do?”

That got a big laugh from the preview audience when I saw the film — as did the Cheney-like veep as soon as he showed his face. This may be because we half expected it. What else would a Hollywood political villain look like these days if not Dick Cheney? And there he is, like the devil in the old morality plays with his mask and tail and horns. Of course he must be made to admit to political error, as in a show-trial confession, after disaster strikes and the smug scientists say: “You didn’t want to hear about the science when it could have made a difference.” Oh dear. If only we had listened!

But the movie skates over the fact that it never could have made a difference. Even the most fanatical global-warming activists don’t suppose that any changes we could make would stop or slow the warming trend in less than decades and this is, well, “The Day After Tomorrow.” The fictional Cheney is also right to point out that the economy is at least as fragile as the environment, and it is not self-evident that the former ought to be sacrificed to the latter, with all the misery we know that would produce, when we know so little about how to effect climate change anyway. But none of this matters to the nerd’s fantasizing, which expresses the pent-up frustration of the intellectual who has not been allowed to run the world in the fashion of Plato’s Philosopher-King.

Meanwhile, back in the real world, as S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine reminds us, the nerds actually did come to power in Cambodia and proceeded to wipe out a third of the population. They called it Year Zero, a totally new beginning, and Emmerich’s fantasy in which the former superpower must make a new start with only a remnant of its former population bears an eerie similarity. Here nature plays the role of the Khmer Rouge, so that the wiping out of millions can be done guilt-free, but the wish to make an absolute break with the past is the same. Surely it is of some significance too that when Jack Hall’s son, Sam (Jake Gyllenhaal), is trapped with a few others in the New York Public Library, they have to burn the books there to survive. That’s the kind of thing that happens when intellectuals come to power, either in reality or in fantasy. Year Zero: the past obliterated. You just wouldn’t have expected Hollywood to be so frank about it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.