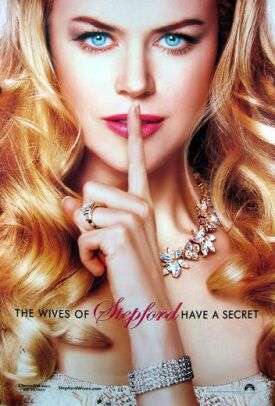

Stepford Wives, The

If you go back now and watch the original Stepford Wives — the 1975 version adapted from Ira Levin’s novel by William Goldman, directed by Bryan Forbes and starring Katherine Ross — you may find yourself laughing more than you will at the new version — written by Paul Rudnick, directed by Frank Oz and starring Nicole Kidman. But in 1975 it wasn’t supposed to be funny. Now it is. And when you think about it, what else could Messrs Rudnick and Oz have done with such material? Women’s horror at the idea of being transformed into domestic automata now seems a distant memory. Today, as Daphne Merkin wrote in an article in the New York Times Magazine a few years ago, women are made to feel ashamed not for spurning a merely domestic existence but for wanting one, as many still do.

Even if they feel, or claim to feel, the contempt of a Hillary Clinton for women who stay at home and bake cookies, with the best will in the world they can hardly fear the prospect of being forced into such a life themselves. It’s much more likely that they’ll be forced to have careers in order to pay for the kids’ day-care. In other words, there goes 90 per cent of the emotional energy of The Stepford Wives, whose power as a paranoid feminist fantasy has now dwindled to the merely proverbial, as in “she looked like some kind of Stepford wife.” So why remake the movie then? Why does Hollywood do any of the crazy things it does? In sheer practical terms, the surprise of Katherine Ross’s discovery of her robotic alter ego was spoiled for us a generation ago. But then so was the surprise of Psycho, and Gus Van Sant remade the movie — disastrously — anyway.

At least the new Stepford doesn’t make the mistake of trying to re-create the original shot-by-shot. Instead, it updates the story by making the heroine, Joanna Eberhart (Miss Kidman), the head of a Fox-like network who loses her job when her latest reality series, “I Can Do Better,” induces a wife to leave her husband for better sex elsewhere and the husband, in consequence, to start shooting people. So Joanna and her mild-mannered husband, Walter (Matthew Broderick), who now has a different surname, decide to move to Connecticut to make a new start. There the Stepford Men’s Association, presided over by the reliably sinister Christopher Walken, appears almost from the beginning to be involved in the robotics business — now not out of any attachment to patriarchal tradition as such but because the Stepford husbands are, like Walter, all made to feel emasculated by their more successful wives.

The idea of making the story into one of revenge for the successes of feminism is a bit more promising, but the film-makers do not pursue it very far. The fires of ideological passion do not burn brightly here, one way or the other. Apart from a new surprise ending — which of course I shall not reveal — the main changes to the original are two. One is a character called Claire (Glenn Close), who seems to act as the mother superior to the Stepford wives, leading them in “Clairobics” while they are dressed in full 1950s housewives’ kit, including high heels: “Whatever we do,” Claire explains, “we always want to look our very best.” The other is less the introduction to Stepford of a gay couple, Roger and Jeffrey (Roger Bart and David Marshall Grant), one of whom is Stepfordized into a gay Republican candidate for the state assembly, than the introduction of the whole gay sensibility that comes with Mr Rudnick. Both he and the movie find the very idea of the Donna Reed-style ‘50s homemaker intrinsically comical.

In fact, we all do since we learned to look at the straight guy — and gal — through the queer eye. The Stepford wife is just so gay. How could we not have seen it before? That’s why you see over the opening credits images apparently taken from 1950s TV commercials, all of them featuring beaming housewives performing domestic chores or submissive, feminine types gazing adoringly at their hunky male companions. At one point, when Claire, presiding over the Stepford women’s book club, gently turns aside Joanna’s enthusiasm for Robert Caro’s Life of Lyndon Johnson in order to introduce the book she wants to talk about, Christmas Keepsakes and Collectables, gay Roger joins the Stepford wives in enthusiastically commending her choice.

Mr Rudnick is an immensely talented writer, but it may be that not everyone will crease up at the mere sight of the hitherto slovenly but now Stepfordized Bobbi (Bette Midler), Joanna’s best friend, in a full skirt and a tight bodice, with lots of make-up and big hair, smiling as she greets her friend with a tray full of cookies. That is at least partly because, even though the women are no longer murdered and replaced by robotic duplicates but only have some computer chips implanted in their brains, the underlying concept is still too dark to permit this and other attempts at humor to succeed entirely. And the ending, which was reportedly re-written and re-shot after the original tested badly with focus groups, is a mess.

The film doesn’t help itself either when it tries to draw a new and resoundingly banal moral out of the material: namely, that it is foolish to seek perfection in a mate. This is perfectly true, but quite beside the point, which has only incidentally to do with perfection and primarily with power and dominance. To make of it such an innocuous bit of moralizing is to destroy such potency as the idea of manufactured submissiveness still retains. How much better it would have been if the filmmakers had known what to do with the climactic confession by the mastermind of the Stepford wives’ project that “All I wanted was a better world, a world where men were men and women were — cherished!” It’s not exactly perfectionism, whether of the real world or of the Stepford variety, to feel the attraction of that vision.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.