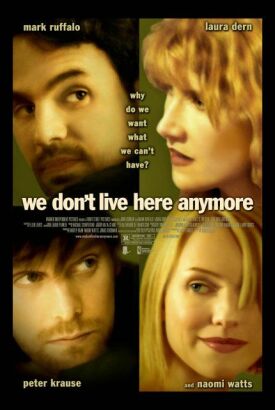

We Don’t Live Here Anymore

Chekhov said that if you show the audience a gun in the first act, it had better be fired before the end of the play. And, he might have added, that goes double for the movies — if movies had been around then. I won’t say whether or not We Don’t Live Here Anymore is guilty of a similar trespass against the rules of well-crafted drama, but I will say that on that question hinges that of what we are to think of the film. Adapted from two short stories by André Dubus by Larry Gross and directed by John Curran, it is about adultery. You may have heard about it. Hank (Peter Krause) and Edith (Naomi Watts) are best friends with Jack (Mark Ruffalo) and Terry (Laura Dern). Hank teaches writing, Jack literature, at the same small New England college. They talk about books, sports, women. They go running together. And each lusts after the other’s wife.

Jack and Edith are the first to get together. This is a bit of a surprise because it is Hank who is the serial philanderer and Jack and Terry who seem to have the rock solid marriage. But Edith is embittered by Hank’s infidelities, which have so vitiated their relationship that by now, Edith insists, Hank doesn’t even care if she is unfaithful too. Yet at some level she herself must doubt this, since she is so obviously out for revenge. Jack’s motivations are harder to judge. Probably he is just obeying the male imperative to scatter his seed abroad. The problems opened up in his own marriage by his actions look a little suspicious: as if he, and probably Terry too, have had to create them — as a pretext in his case and an explanation in hers. For both, the desire to find a reason for what they are doing is at least as strong as the sex urge.

Partly this is because, Hank and Edith’s marriage being an emotional wasteland, all the displaced feeling sloshes into Jack and Terry’s, and they don’t really know what to do with it. Hank really doesn’t care about Jack and Edith’s affair, and his seduction of Terry is less a matter of revenge than of opportunism. She is just one more notch on the bedpost to him. So as neither Jack nor Terry have the excuse of a grand passion elsewhere, they are forced to turn on each other. Their complicity in reconstructing the story of their marriage to match the circumstances that they would prefer to think they had no control over is the best thing about the film. Even when Jack suggests that he is turned on by the thought of Terry’s infidelity with Hank, and Terry hurls back at him the accusation of being a “pervert” — but only after describing (for him? for herself?) just how much she enjoyed it — it’s as if they still aren’t playing for keeps but merely titillating themselves with naughty fantasies.

Both Mr Ruffalo and Miss Dern do very well at carrying us along with them as love turns to hate and back to love again in an instant. All the petty resentments between them that would never otherwise be noticed suddenly become of immense importance. Terry goes from being moderately slovenly in her housekeeping to a complete neat-freak and back to utter slobbery in response to Jack’s complaints. And all along we are aware of the element of self-dramatization on both sides. Jack accuses Terry of not understanding him, Terry accuses Jack of not knowing her. The false note is unmistakable. It is himself that Jack doesn’t understand, just as it is herself that Terry doesn’t know. At times they must realize this themselves. When Jack tells their worried children that their parents’ fighting is “just adult foolishness” he is at least as sincere as he is anywhere else in the movie. The question is how far do the film-makers realize it?

And that’s where the gun comes in. It’s not an actual gun, of course. These are good liberal college professors with beards, in the case of the gentlemen, and that dressed-down, low-paint, natural look of the academic wife, in the case of the ladies. But Mr Curran keeps showing us the same railroad crossing with the same freight train speeding through it (Anna Karenina comes inevitably to mind), the same rocky stream with a long drop into very cold water, and teasing us with the prospect of somebody’s eventually doing something, well, unforgivably real. Of course it would be very wrong of me to reveal that somebody does or doesn’t, but an attentive viewer may be able to predict which it will be by how seriously he or she is finally able to take the emotional excess on display in the adulterous quadrille that the movie is mainly concerned with.

Everything in the end comes down to forlorn Edith’s forlorn question to Jack: “Everybody deserves to be happy, right?” Only here does she — and, some may say, the film — become morally serious. Her husband doesn’t deserve her fidelity. Obviously, though no one knows why, she hasn’t deserved his. But everybody deserves to be happy. Right? On that one shining moral truth all the action and inaction of the film depends. It is the principle for which all four have, ironically, sacrificed what happiness they had, and yet no one is really any more sure of it, or of anything else, than Edith is. At the heart of the film there is nothing but a vacancy. But if we can live with that, it’s because the film-makers have recognized that we already do.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.