Motorcycle Diaries, The

The reading this week, brothers and sisters, is from The Black Book of Communism by Stéphane Courtois and others. There you will find that, at a conservative estimate and not counting deaths in war, in the last century Communist régimes worldwide have killed 20 million people in the U.S.S.R., 65 million in China, two million each in North Korea and Cambodia and one million each in Vietnam and Eastern Europe. Add to that number 150,000 in Latin America and a million and a half or so in both Africa and Afghanistan and you get a total of about 100 million.That’s a one with eight zeroes after it. 100,000,000. People. Yet no matter how many millions were murdered in its name, no matter how disastrous in human as well as economic terms it has proven to be at every time and in every place it has come to power, Communism still has the power to capture the imagination, especially of the young and idealistic.

Ever since he was killed by Bolivian soldiers in 1967 while attempting to foment yet another ruinous revolution, Ernesto “Che” Guevara has been a world-wide icon of just that youthful idealism, his silk-screen print with the wild hair, defiant whiskers and black beret has hung on thousands of dorm-room walls and been emblazoned on millions of T-shirts. Do all those kids not know about Communism’s woeful history? The answer is that they probably have a vague idea of it — and that that, both vagueness and idea, is probably just what they like about Che. That is to say, they know he’s a dangerous guy. Following his example can get you killed. He is the rock star, the shock jock, whose flirtations with violence, death and obscenity gratefully scandalize their parents and respectable society. To them, Che is a symbol. He stands for youth and attractiveness combined with high ideals, strong principles, defiance of authority (and of course the old people who exercise it) and ruthless methods. It just doesn’t matter to them that the ideals were false, the principles misconceived and the authority in many cases legitimate, or that the methods resulted in the deaths of a lot of people they didn’t know.

Che’s real historical importance is that he, along with his patron Fidel Castro, invented gestural politics. Gestural politics is kid politics, and 15 years after “the end of history,” kid politics sometimes seem like the only kind of politics there are. Even in our democracy our political leaders attempt to “brand” themselves in the political marketplace by making the right gestures. Senator Kerry is the sensitive, “nuanced” brand, more appealing to women, minorities and young people, while President Bush stakes out his claim to the tough guy vote — even as the two of them seem to find less substantively to disagree about than Pepsi and Coke.

That too is part of the reason why the legend of Che goes sublimely on. A rock star from the age that invented rock stars, he set the stage for heirs, like Subcomandante Marcos of the Chiapas rebellion in Mexico, who have grown more interested in marketing themselves as romantic revolutionaries — Read the book! See the movie! Buy the T-shirt! — than actually accomplishing their ostensible revolutionary aims, assuming there are any. The collected writings of the Subcomandante — even the rank that he confers upon himself is shockingly humble, almost apologetic — says it all: Our Word is Our Weapon. Not that gestural politics need be lacking in firepower. As more than one commentator has pointed out, the world’s latest rock star guerrilla in the Gueveran mold is Osama bin Laden. Not only does the bearded guy in the turban get the same T-shirt treatment as the bearded guy in the beret in large parts of the world, but both have made their revolutionary fortunes out of their hatred of the United States of America, or “the great enemy of mankind” as Che called us.

Yet American teenagers still lead the world in worshiping the latter’s image. Of course Che’s many murders are now a long way in the past and took place somewhere else, while Osama’s were here and are still fresh in our minds. But maybe in another forty years a new generation of New York teenagers will dart past the World Trade Center memorial on their hover-boards wearing Osama sweat-shirts. Osama’s version of Islamism is also just as reactionary and obscurantist as Che’s version of Communism was. Osama’s pan-Islamism echoes Che’s pan-Hispanicism — “a united America, from Mexico to the Magellan Straits, with a single mestizo race” — and both men appeal to a poor people’s nostalgia for an idealized past, symbolized for Osama by the Ottoman Caliphate and for Che by the Incan imperial city of Machu Picchu.

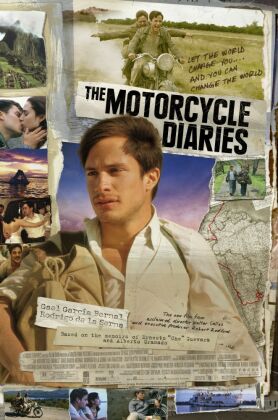

Walter Salles, the Brazilian director of the wonderful Central Station, shows that he knows the basis of Che’s appeal in his latest movie, The Motorcycle Diaries. “I wish you could see us,” his Che, played by the Mexican heart-throb Gael García Bernal (Amores Perros, Y tu Mamá También), writes to his sister of himself and his friend Alberto Granado (Rodrigo de la Serna). “We look like outlaws, commanding attention wherever we go.” How gratifying he would have found it to know that he was still commanding attention over half a century later. And not for his actual outlawry but for the most romantic and innocent episode of his life, a journey he took with Granado in 1952 by motorcycle, foot and thumb for seven months and nearly 8000 miles around the continent of South America, starting in his native Buenos Aires and ending seven months later after traversing Argentina, Chile, Peru, Columbia and Venezuela, in Caracas.

According to the Che-legend, this was when our hero, a young medical student, was radicalized by observing at close hand the sufferings of the poor. Salles wisely sketches in the suffering poor with a very light hand, however. In fact, apart from a couple of committed Communist itinerant workers, one or two Indians and the lepers in a Peruvian leper colony where the two young men work for a time, the poor will leave almost no impression on the movie audience — at least not compared with the beauty of the landscapes through which the two boys travel and the fun they have — as anybody would at that age. And who can quibble with that? It is Che’s universality that still interests us, his paradigmatic figure as young, handsome and ready for adventure — much more than the compassion for suffering which has, since his time, become a little shop-soiled as the vulgar affectation of every Oprah or Geraldo on TV.

The only problem with Salles’s film is that it does not allow him any distance from his subject, and distance is necessary if it is not to lapse, as it does lapse in the end, into hagiography. Those murders should, at a minimum, not have gone completely unmentioned. But Salles ignores them in the interest of making Che into a Latino James Dean, his three-years’ junior contemporary. For both, dying young was part of their job description as icons of the youth culture. But anyone less susceptible than a teenager to that kind romanticization of youth must regret that the film simply ignores the human misery associated with all that this young man ultimately stood for. It’s one thing to treat with respect one of the heroes of the worldwide countercultural revolution of the 1960s — whose repercussions are still re-echoing down the decades — and quite another to treat it uncritically. Neither Che nor Fidel may have lived long enough know better, but Salles ought to have done so.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.