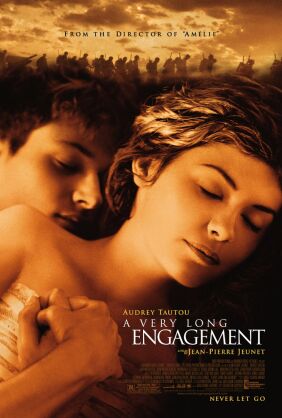

Very Long Engagement, A (Un Long Dimanche de Fiançailles)

Jean-Pierre Jeunet, the creative force behind A Very Long Engagement (Un long dimanche de fiançailles), has always been a quirky director. In fact, “quirky” is putting it mildly. His early films, Delicatessen (1991) and City of Lost Children (1995) often seem like illustrations for the definition of “post-modern” proposed by Moe Sislak of “The Simpsons,” which is “weird for the sake of weird.” But with Amélie (2001) he seemed to find a style and a star that not only suited him but that produced an enormous popular success. It is still the largest grossing French movie in France there has ever been. The style was one of post-modern whimsy joined to a sweet but sentimental love story that reached beyond itself to look as if it meant to put the whole world to rights. The star was the lovely and lovable Audrey Tautou. Now he is back again with the same style and the same star and an equally enjoyable romp.

Miss Tautou is here made even more adorable by being an orphan and having a limp, caused by a bout of polio. Jeunet even takes up again the theme of Amélie, namely the power of the love of two attractive young people to change the world — or at least the magical, weird-for-the-sake-of-weird world he is at pains to create here. And there are some of the same problems too, most notably the near epic scale of the canvas on which he is working, which comes across as being too crowded, too confused with incident and characters who would be interesting in their own right but seem too distantly related to the main story. Most importantly, even more than Amélie, A Very Long Engagement cannot avoid an eventual collision with reality.

But Jeunet seems deliberately to court this collision by beginning in a World War I trench on the Western front as five French soldiers are being led forth to execution. You don’t get much more real than that. In fact, I would say that the common view of “reality” as something sordid and horrifying which lurks beneath pleasing but deceptive appearances actually arose out of the trenches. Each of the five men has been sentenced to death for self-mutilation in a desperate attempt to escape from the hell of war at the front. As they are led through the trench to what is meant to be their final hour, Jeunet gives the back story of each, and how he came to this unfortunate pass in a trench with the weird name, even in French, of Bingo-Crepuscule.

The most poignant and memorable of the men is the still boyish Manech (Gaspard Ulliel) from Brittany, also known as “bleuet” or “cornflower,” as the increasingly young draftees were called late in the war. He has gradually had his wits turned by the horrors of the war and finally snaps as a friend next to him is blown to pieces by a shell, the pieces ending up all over Manech. Along with the other men, he is sent forth into no-man’s land, which all of them recognize as a certain death sentence. Thus for the sake of their families they may be listed as killed in action. But when the word comes home to Manech’s young fiancée, Mathilde (Miss Tautou), she doesn’t believe it. So strong is the psychic bond between them, she believes, that if Manech were dead, she would know it independently. So, after the war she sets out to find him, or at least to find out what happened to him, with the help of an influential friend (André Dussollier) and a private detective she hires herself (Ticky Holgado).

In doing so, she learns of the rough justice meted out to Manech at the front, but she looks in vain for anyone who can confirm his death. Meanwhile, the search entangles her in the back-stories of the other four men as well as three others who were present in Bingo-Crepuscule on the fateful day and an officer who chose to ignore a telegram from Paris commuting their sentences. All these strands of narrative woven together produce such a shaggy-dog story that Jeunet even includes a shaggy dog with gas problems as if to confirm it. Feisty Mathilde’s foster mother Bénédicte (Chantal Neuwirth) is fond of repeating a little French rhyme translated here as “doggie fart gladdens my heart.” I wonder if Jeunet or Guillaume Laurant, his co-adaptor of the novel by Sébastien Japrisot knew that the English word feisty may derive from dialect and Middle English words meaning “a farting dog”?

For American viewers, the most memorable thread in the Jeunetian tapestry may be provided by Jodie Foster — her accented French is attributed to her being Polish — as a military wife who sleeps with another man in order to get pregnant, in order to get her husband sent home from the front — and who thus finds love, or at least sensual delight, for the first time.Another director might have found enough material for a movie in this vignette alone, which takes up about ten minutes’ worth of Jeunet’s account of Mathilde and Manech’s story, to which it is only tangentially related. But Jeunet is as usual a prodigal with his narrative materials and prefers to shoot off in a dozen different directions at once, perhaps as a way of suggesting the largeness of the central episode, and its significance beyond itself.

And this is where reality, and not just the conventional reality of trench warfare, really does come into it. All the various subplots, each with its own bizarre touches, help to create for the main story of Manech aime Mathilde a sense of “magic realism” whose purpose, I take it, is to prepare us for something wonderful, if not quite miraculous, in the dénouement. But I find that it has the opposite effect. The excess of extraordinary and original imagery earlier in the film detracts from the emotional impact of what ought to be an even more extraordinary conclusion, rather than adding to it. Clearly, we find ourselves in a world where the remarkable and even the miraculous are everyday occurrences. Still, the lush excess of cinematic sweets does keep our attention for more than two hours and, together with the ever-adorable Audrey Tautou, makes this a movie worth watching.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

![Inglorious Bastards [QT, note SP]](https://jamesbowman.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/ingloriousbastards.jpg)