Cutting Moral Corners

From The New CriterionLast month I wrote in this space about the “Two Nations” contained within America’s borders — not the rich and poor nations of John Edwards’s anachronistic fancy but the clever and the stupid, the complicated and the simple, the sophisticated and the boorish nations symbolized for many in the now ubiquitous red and blue map of the election results. Of course no one supposes that there are not clever, complicated and sophisticated people voting for Kerry in the red states and stupid, simple and boorish people voting for Bush in the blue states, but bright Kerry supporters versus dim Bush supporters was the accepted model wherever you looked in the media, many of whose sour post-election commentaries were based on the assumption that the blue states had for some reason been blessed with majorities of bright people while the red states were correspondingly cursed with majorities of thickoes. More than one liberal commentator echoed Carole Simpson, former anchor of ABC’s World News Tonight, in noticing that the 31 red states included the thirteen that made up the old Confederacy at the time of the Civil War and put the difference between red and blue down to the legacy of slavery. Or slave-owning.

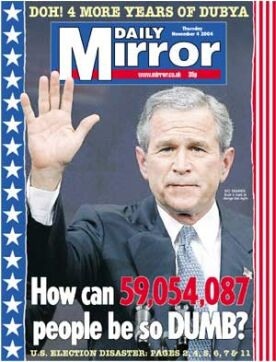

But wait a minute. Isn’t there something wrong with the whole idea of statewide majorities of smart people? Doubtless there are majorities of bright people at places like the Microsoft campus in Redmond, Washington or Harvard University or at 229 West 43rd Street in Manhattan and precincts adjacent thereunto, but how can the entire states of California or Illinois or Pennsylvania (just barely) be majority bright? Doesn’t that work a bit like Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegone, Minnesota, where all the children are above average? Even in Massachusetts intelligence must be just a bit rarer a quality than that. The wonder, then, isn’t that the bright people’s party didn’t get 51 per cent of the vote; the wonder is that it got as much as 48 per cent. Kerry voters got a big kick out of the headline in the Daily Mirror of London: “How can 59,054,087 people be so DUMB?” But really, speaking as one of the dumb majority, I find there’s no mystery about it. Most people are pretty dumb, at least by the standards of John Kerry and many of his most vocal supporters who manned, I think even they would have to admit, the commanding heights of the culture. Much more mystifying, I would have thought, is the question: “How can 55,532,981 people be so SMART?

Except that I think I’ve figured out the answer. It is, as I suggested last month, that the Kerry voters weren’t necessarily all that brainy. For it wasn’t being smart that made people vote for Kerry; it was voting for Kerry that made people smart. It’s simple, really. The Democrats are by now well-established as the political home of clever and sophisticated people. Not only famous geniuses like Philip Roth and Simon Schama and Madonna but most non-famous college professors and scientists, writers and artists, actors and musicians, journalists and gay people. Under those circumstances, what better way for someone to demonstrate his own intelligence and sophistication, especially if he is the tiniest bit insecure about them, than by associating himself with all those social and intellectual luminaries — among which, as the Mirror reminded us, we have to include a large majority of the frightfully clever British — by voting for their political party? You could call it the Mensa tendency in American politics, except that to get the bragging rights of your grey matter by joining Mensa you have to pass a test, while demonstrating socially creditable political smarts only requires you to fill in your electronic ballot form correctly — which, notwithstanding post-election conspiracy theories, I stubbornly persist in believing nearly everyone did — and perhaps put a “Kerry/Edwards” bumper-sticker on straight.

I think it was Charles Murray and the late Richard Herrnstein in The Bell Curve (1994) who first identified “the cognitive élite” as a new social class poised to supersede declining ones based on wealth or region, race or religion, but their insight was lost in all the fuss about race and the heritability of IQ. We should have seen then that among the political consequences of the growth of a self-identified élite based on intelligence and education would be the increasingly vitriolic hatred for someone like President Bush — a Yale and Harvard man who is a kind of class traitor for courting the “some college” and lower social orders that still predominate in the red states. In America, many things may qualify one for membership in the cognitive élite, including university attended, number of years there completed, number and level of degrees earned, books, newspapers or magazines read (the New York Times and The Nation are automatic qualifiers), films or TV shows watched (“The West Wing”or “Sex and the City” will do it, but no “reality” series screened to date), radio broadcasts listened to (NPR is always a safe bet) or art reproductions on your walls (Andy Warhol or Francis Bacon, yes, Leonardo or Botticelli, no, and nothing before Matisse unless it’s an ironic icon). But in lieu of any or all of the above, a vote for John Kerry in November was enough to put you in.

None of this is obscure knowledge. “Every liberal,” says Paul Begala, late of the Clinton administration and now of CNN’s “Crossfire,” imagines that he is “intellectually superior to conservatives.” And by the same token, “Every conservative I know wants to think of himself as morally superior.” This is absolutely spot-on except for the bit about conservatives, certainly if it is meant to imply a contrast with Kerry voters. It wasn’t a conservative who wrote, as Peter Beinart did in The New Republic, that “honest conservatives, even those who admire Bush, know he didn’t earn a second term.” As the editor of a magazine which has been monotonously proclaiming the president’s dishonesty since well before 9/11, he must have come by degrees to think it no great leap from that assumption to assuming all the president’s supporters were as mendacious as he. How can 59,054,087 people be so dishonest? Later Beinart apologized but, like Kerry apologizing for accusations of war crimes against his once and future “band of brothers,” he made it sound as if he had only been guilty of a poor choice of words. And Beinart’s insult was one of the milder remarks from bitter Kerry partisans who were given access to the public prints in the weeks after the election. The novelist Jane Smiley, writing in Slate, insisted that Bush and Cheney, if not every one of their supporters (who are merely ignorant) “know no boundaries or rules. They are predatory and resentful, amoral, avaricious and arrogant.” Garry Wills in the New York Times proclaimed the end of the Enlightenment, no less, and found little or nothing to choose between al Qaeda’s jihad and George Bush’s.

No self-conceit of moral superiority there then! But the idea of conservatives as being more than commonly self-righteous, just like the idea of liberals as being more than commonly intelligent, has now become an article of faith for the media consensus and the reason for all those sober electoral post-mortems announcing the importance of “moral values” in explaining the results. I myself thought this analysis mistaken. “Moral values” as cited by people in exit poll interviews amounted to a “Don’t Know” response for anyone who had a vague feeling that one side was preferable to the other but couldn’t tell you why exactly, and it’s not surprising to me that Bush should have had more of these voters, given the rhetorical differences between the two campaigns. Kerry, in other words, always had a great many reasons to offer why people should vote for him, while Bush had only one or two on the other side. If you cared more about “leadership” or resolution than you did about taxes and health care and all the rest of the usual campaign “issues” what other box would you check than the one marked “Moral values”? The idea of such values as a new and potent force was also counterintuitive. The electoral map in 2004 looked almost exactly like the one in 2000, except that the red tide lapped just a little higher on the blue beach, taking in New Mexico and Iowa which it just missed last time and only losing New Hampshire, which it just won last time.

“Moral values” may not have decided the election, but they did create the passion with which it was fought and the bitterness of the aftermath. Anyone attending to the electoral dialogue in the weeks and months running up to the election could not have been unaware that all, or nearly all, the moral fervor was on the Kerry side, which numbered among its more fervent adherents the thoughtful graffitist who inscribed on a public refuse bin near my office the elegant equation: “Bush = Hitler” This was not, by the way, the first time I had been involuntarily made aware of this sentiment’s being abroad, but I don’t remember a single conservative writing Kerry = Hitler. Or even Kerry = Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, take your choice. Even among the more rhetorically restrained Democratic faction, charges of “bigotry” against Bush/Cheney were almost routine. Those who liked Bush did not, for the most part hate Kerry or consider him a wicked or immoral man, whereas large numbers of those who liked Kerry did have just such thoughts and feelings about the President. I suppose it would have been too much to expect that those who were the victims of it should have been able to spot the irony that the party of “nuance,” of insisting that all was not black and white, professed to find it all black and white when it came to the Bush administration. At least Bush’s with-us-or-against-us moment was vis á vis an evil dictator; theirs was against their own government.

So if the side for which moral values mattered most actually lost, then wasn’t it the case that the vox populi had come down against a greater moralization of politics? Once again the media consensus had got things exactly wrong. But then the whole point of the media consensus is to allow journalists to be wrong, even absurd, with impunity. Without the license it affords for rhetorical recklessness there could be no Maureen Dowd to write that Bush had been “re-elected by dividing the country along fault lines of fear, intolerance, ignorance and religious rule”? Her scrambled metaphor, if it meant anything at all, required us to believe that such “fault lines” did not already amount to divisions and would have troubled no one if Bush, here possibly imagined as an elemental force wielding the power of an earthquake, had not come along to knock off onto his side of the fault line or lines all the fearful, intolerant, ignorant and theocratically minded to whom otherwise such regrettable mental habits would never have occurred. But here she has also the advantage of appeal to a further article of the post-election media consensus, namely that the nation is “deeply divided” — whether Bush and his henchmen actually created the division or only exploited it — which is at least equally dubious. Such division as existed was mainly a phenomenon of the media culture which found itself unexpectedly divided from the majority.

As even the Washington Post editorialized, “although citizens are not deeply divided, the minority that dominates the political arena is genuinely polarized.” This, at least, is beyond question and something the Post attributes to, among other things, the fact that “television, once a force for unifying moderation when three networks ruled the air, is now the province of noisy cable shows that thrive by staging furious arguments.” Now it seems to me just a bit of an exaggeration to say that a few shows with minuscule audiences like CNN’s “Crossfire” or MSNBC’s “Hardball with Chris Matthews” have come to amount to the whole “province” of television, but this faux insight is something that looks like becoming yet another bit of the media consensus. That’s why Jon Stewart, the comic news-reader of Comedy Central’s “Daily Show,” went on “Crossfire” before the election to tell Mr Begala and his co-host, Tucker Carlson, that their noisy partisanship was “hurting America.” It was not coincidental that he, like the Washington Post, had announced that he was supporting Kerry. For what he had in mind as the media ideal was, I suspect, also what the Post meant by that “force for unifying moderation” in the old network news shows. “Moderation” here means, as it so often does in media-talk, “the political tendency that I favor.”

In any case, even the Washington Post must have had a hard time clinging to the polite fiction of the networks’ moderate and unifying qualities in the aftermath of this election campaign, which saw an unprecedented amount of partisanship on the part of media outlets who were once so jealous of their reputation for “objectivity.” CBS was particularly at fault — blatantly anti-Bush in broadcasting scurrilous charges against the President’s record in the Air National Guard which were based on forged documents and pushing hard, along with the New York Times, at an almost equally bogus story in the closing week of the campaign about some missing munitions in Iraq that it obviously hoped would amount to an “October Surprise.” In the latter case, CBS freely admitted that it had intended to hold the story until only two days before the election and was only forced to let it out early when the Times published it in order to forestall a leak. But when the story was published, no one knew when the explosives stored at Al Qaqaa had gone missing, or whether they had been moved by Saddam Hussein before the war or blown up by American troops during it. And if there were any negligence, it would have been as a result of an operational decision and not one that anyone could reasonably have expected to have crossed the desk of even a low-level bureaucrat in Washington, let alone the President’s.

But desperation on the part of Kerry partisans to find anything that could be made to look like a scandal was enthusiastically taken up by the press, which laid particular stress on the charge that the missing explosives “could be used to detonate a nuclear device.” This was like saying, if a box of screws had gone missing, that the screws could have been used to construct a nuclear device. Well yes, they could, but you would have needed quite a lot of other things as well — a lot of other things that the media itself has been several times at the point of apoplexy over the past year and a half with the effort to emphasize that the Iraqis didn’t have. It’s true that such manufactured scandals were only one manifestation of the fact that that is the way the media play the political game, but there were no such scandals, and no attempts at scandal in the case of Senator Kerry. On the contrary, when the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth attempted to drum one up, no one in the media paid the slightest attention until Kerry was stung into replying. And then, at least in the case of the New York Times, it was only to investigate whether the Veterans had ties to the Bush campaign. Through all this the media naturally continued to deny that there had been any lapse from “objectivity,” often in terms reminiscent of Dan Rather’s comic dismissal of those who had called attention to his journalistic lapse in making a report based on forged documents as “partisans.”

The pretense of the media’s non-partisanship has been looking more and more hollow for years, perhaps because of the influence of the more open partisanship of the cable shows mentioned by the Post editorial. But it finally collapsed completely under pressure of the furious hatred for President Bush felt by the smart people of the media culture. It wasn’t just the call made by Kerry’s campaign manager, Mary Beth Cahill, to NBC on election night to urge them to unaward Ohio to Bush after the network’s psephological wizards had determined that he must have won the state. Karl Rove also called Fox to urge them to call New Mexico for Bush. Neither call achieved its intended result, but they were significant in terms of where each side thought it might have been able to exercise its influence. Rove could hardly have hoped to be listened to anywhere but Fox, but NBC was the outlier among the other networks, which had all been as cautious with their late night projections as the Kerry people could have desired. We also know that the Democrats were as persuaded as the Republicans that the vast majority of the media were on their, the Democrats’, side because of the e-mailing campaign to major and reliably liberal media outlets co-ordinated by the DNC. A well-known on-air figure at one of the networks which might have been considered among the more friendly to Kerry told me that he had received hundreds of e-mails a day from Kerry supporters throughout the campaign, trying to steer his coverage of it in their direction. He had heard from other journalists that the same thing was happening elsewhere and didn’t see how his or anyone else’s coverage could have remained quite unaffected by the fact that so many steely and unforgiving partisan eyes were constantly upon him.

Evan Thomas of Newsweek — no conservative he — notoriously predicted early in the campaign that the media’s pro-Kerry bias would be worth five percentage points to the Democrat in the final tally. The media’s partisanship even became a joke to the media itself. “Television did a good job Tuesday night, I thought,” said Andy Rooney on 60 Minutes, the show that had first broadcast the story based on forged documents. “I know a lot of you believe that most people in the news business are liberal. Let me tell you, I know a lot of them, and they were almost evenly divided this time. Half of them liked Senator Kerry; the other half hated President Bush.” Like Democratic jokes about the dead voting, or the living “early and often,” in Chicago and elsewhere where remnants of the old Democratic machine politics survive, this kind of flippancy amounts to a nod and a wink to the rest of us who are expected to treat such trifling improprieties as their entitlement — perhaps for being better and smarter than the other side. For in fact there is no dichotomy between the moral and the intellectual of the type suggested by Paul Begala. Those who think of themselves as intellectually superior also think of themselves as morally superior — as we saw most vividly in the reaction of so many of the smart people’s faction to their unexpected defeat. And there’s nothing like being persuaded of one’s general and massive moral superiority to reconcile one’s conscience to cutting a few moral corners here and there or giving vent, now and then, to a little “hatred” and “bigotry” of one’s own.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.