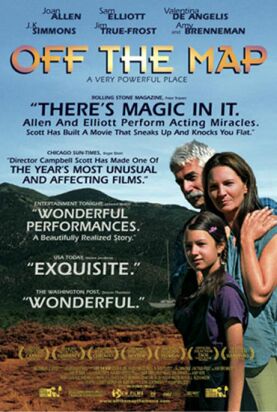

Off the Map

Campbell Scott’s Off the Map, adapted for the screen from her own play by Joan Ackerman, is a highly atmospheric drama set in New Mexico in the 1970s that looks as if it is going to be pathography — the story of a man who suffers from depression and the effect his illness has on his family — and ends up being something quite different. Charley Groden (Sam Elliott) — no relation to the actor and talk-show host with a similar name — is the depressive. He lives in a desert shack that really is off the map with his wife, Arlene (Joan Allen), and their daughter, a precocious, imaginative child of maybe 12 or 13 called Bo (Valentina de Angelis), both of whom are beginning to lose patience with Charley, though for different reasons. Arlene has the job of keeping the family together on virtually no income without any help from Charley. What little money they have comes from her job teaching men in prison to read. Bo, who sees her father’s depression as being “like a geological formation by which our lives were defined,” is being home-schooled by her mother but has a natural teenage urge to escape. She finally decrees that she has decided to go to high school.

There are hints that Charley’s depression may have something to do with service in Vietnam, but they are not followed up. Otherwise it is presented as a given, a visitation from God upon a man who is by nature and has been until recently happy and sanguine in temperament. The story, told by the grown-up Bo (Amy Brenneman) in flashback, is meant to be seen in relation to her grown-up self, but we see too little of that for it to be anything more than a framing device. It begins with the arrival at their desert home of an IRS auditor called William Gibbs (Jim True-Frost). Having had to abandon his car in the desert and walk the rest of the way to the house, to which there is no paved road, Gibbs arrives at the Grodens’ house to find Arlene gardening in the nude. Simultaneously, he is stung by hornets, to which he has an allergic reaction. Perhaps this is exacerbated by the deep impression made upon him by the sight of naked Arlene, but he becomes very ill and is forced to lodge with the Grodens for several days during which he suffers from periods of delirium.

During a lucid interval, Charley comes to talk to him. “Have you ever been depressed?” he asks.

“I have never not been depressed,” Gibbs confides. And then he tells Charley of how he came home from school one day when he was six to discover the body of his mother, who had hanged herself.

“You put me to shame,” says Charley, citing “a good reason like that” when there is no known reason for his own depression.

But when Gibbs recovers, he announces that he has experienced two revelations. One is that he is in love with Arlene. The other is that he thinks his memory of discovering his mother’s body may be unreliable, planted there by an older brother. Both seem to him to be potential exits from depression. It might have been an idea to show the two depressives battling for the hand of the fair Arlene, but this is Bo’s story and is headed in another direction, hinted at when Gibbs tells Arlene not only that he loves her but that the burden of his childhood memory may have lifted and that “the only thing I know to be true is my love for you.”

She replies that “New Mexico is very powerful.”

And so it seems. The tourist slogan, “Land of Enchantment,” is here taken literally, and the family’s desert idyll takes on a charming unreality. In fact, it is a kind of Garden of Eden — as is suggested by the iconic image of naked Arlene amidst her desert flora — into which sexual knowledge has not yet entered, either for Bo as she remembers it or for anyone else. William Gibbs stays on with the family, abandons the IRS and all the rest of his past and becomes a celebrated painter in whose works critics find “disturbing depths of emotion.” But, so far as Bo (and therefore we) can see, the love not only of Gibbs but even of her father for her mother is entirely platonic. Hints of the homoerotic between dad and his best friend, George (J.K. Simmons), are likewise raised only to be abandoned.

Is this Bo looking back on Eden and averting her eyes from what she does not want to see? Is she, like William Gibbs, building her life on the foundation of a manufactured memory? Or is it Eden indeed, a version of the hippie dream of a self-sufficient desert commune but magically purged of the sexual tensions that were the undoing of so many real communes? I think that both Joan Ackerman and Campbell Scott like this ambiguity. In fact, it is their point. This is a fantasy — although it looks like a somewhat dated one by the standards of the first decade of the 21st century — and they mean to make us believe in it one way or the other. Of course, they are helped by tremendous performances in all the leading roles and by breathtaking photography of the New Mexican desert, but you may have the same experience I did of coming away from this Land of Enchantment, shaking your head and finding that it all just disappears, like a dream.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.