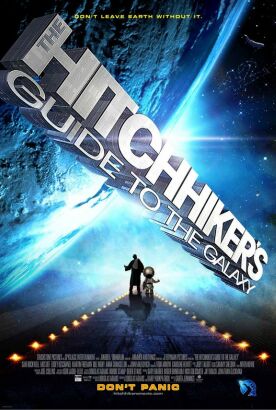

Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, The

Remember the 1970s? Lots of people don’t, of course, but those of us who do can tell you that they were a time for which existential heroes like Arthur Dent in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy were invented. Arthur’s inventor was the late Douglas Adams whose franchise, sometimes nicknamed H2G2, began as a BBC radio series in 1978. This quickly achieved cult status and was turned into several money spinning books and a TV show in 1981. Adams was also closely involved in the new film version of the story, directed by Garth Jennings, until his sudden death from a heart attack at the age of 49 in 2001. He gets a posthumous co-screenwriter’s credit along with Karey Kirkpatrick.

But a quarter of a century later the concept has grown a bit stale, and I think that’s why, though at times quite enjoyable, the film is a disappointment. Hitchhikers, of course, have all but vanished from our modern superhighways and most of their expressways and by-passes, the things that figured so largely in Adams’s 1970s imagination have been long-since built. These may seem like trivial considerations to you, but they had a particular resonance for the original audience. For one of the things that made the original Hitchhiker so popular was that it was not just the collection of interplanetary grotesques it has since become but at least a partly serious tale of an individual battling bureaucracy. Back then, everyone could immediately understand what was implied by its memorable beginning in which a hitchhiker escapes to wander the interstellar wastes alone after the earth is destroyed by a bureaucratically minded race called the Vogons in order to make way for a hyper-space expressway through our star system.

The film tries to re-create this resonance by showing at the beginning Arthur’s confrontation with the local council who are intent on destroying his house for the construction of a by-pass. “It’s got to be built,” says the foreman of the work crew.

“Why has it got to be built?” asks Arthur.

“It’s a by-pass!” says the man, exasperatedly. “By-passes have got to be built.”

Accustomed to today’s traffic snarls, we’d probably agree with that. In any case, most people’s anxieties about the government today have to do not with the fact that it cares too little about us but that it cares too much, constantly involving itself in our lives with the excuse that it is protecting us from dangers — including tobacco and excess flab — that we used to be free to risk without any advice from a nanny state. But the 1970s were full of local and national governments notoriously remote from their constituents and engaged in what they laughably called “urban renewal” projects. These involved tearing down whole neighborhoods of once-thriving but increasingly uninhabitable cities for little or no apparent reason. Sometimes, indeed, for by-passes or expressways.

In such an era, hitchhiker Arthur Dent, played by Martin Freeman in the new film, was a natural hero. A classic “little guy” by no means particularly brave or heroic, he watches helplessly as first his house is demolished by the council and then his planet is demolished by the Vogons. He is only saved by the fact that his friend, Ford Prefect (Mos Def), turns out to be an alien living on earth while working on a new edition of the eponymous Guide. Most Americans, by the way, will not get the joke of Mr Prefect’s name. The Ford Prefect was an underpowered little British-made car from the 1960s that had become a joke by the 1970s. It was a sort of BritishYugo.

Arthur is a perfect parody of the existential hero. He is apparently the last human being in existence — though he later meets up again with Trillian (Zooey Deschanel), an old girlfriend now cruising the hyper-space expressways of the universe as the companion of galactic president Zaphod Beeblebrox (Sam Rockwell) — and he confronts the infinite spaces of the universe with nothing but his little guidebook. Sample advice from the guidebook: “It’s a tough galaxy. If you want to survive out here you have got to know where your towel is.” Again and again Arthur and Trillian survive the aggressive indifference of the universe by the merest chance, all the while on a quest not of their own choosing. Nor are they in search of “the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything” — that has already been determined by a supercomputer called Deep Thought (voice of Helen Mirren) to be 42 — but to the question which fits such an enigmatical answer.”Only when you know the question will you know what the answer means.”

And so he encounters the multiple absurdities of the universe as an unconsidered passenger on the spaceships of its moronic power élites — the two-headed Zaphod, who affects a George W. Bush accent, being the most moronic of them all. “You can’t be president with a whole brain,” says Zaphod cheerfully. Most absurd of all is the story’s God-figure, Slartibartfast (Bill Nighy). Only God is just another working stiff employed by a faceless, multi-galactic corporation engaged in designing and building custom-made planets, even though the collapse of the galactic economy — another echo of the ‘70s — has hit such luxury items particularly hard. Slartibartfast is making a replica of the earth and is particularly proud of his work on the Norwegian fjords. “I won an award for those,” he explains proudly.

It’s a good joke. Or it was 25 years ago. But the very idea of absurdity depends on an expectation of meaning and coherence. In the same way, the idea of the malign indifference of the cosmic spaces depends on lingering expectations of God’s paternal solicitude left over from the era of religious belief. We still had these things back in the ‘70s. Or we were closer to them than we are now. Though of course many people are still believers, culturally we have moved on. Questions about and questing after the meaning of life, the universe and everything now seem as quaint as God did back then. When no one expects the universe to make sense, there is not much artistic juice in its portrayal as a grotesque, gigantic absurdity.

Indeed, there is something slightly frantic about the pace with which Adams’s ideas of the world’s crazinesses are trotted out for our admiration, always in the syrupy tones of Stephen Fry’s voiceover narration. The film begins with the one about the dolphins being the second-most intelligent creatures on the planet, beating the human race into third place, and clearing out when they hear of its impending destruction. They sing a catchy tune called “So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish” while executing Sea-World type acrobatics like an aquatic chorus-line. Then a moment on Planet Earth, as Arthur vainly tries to prevent the demolition of his house, is succeeded by a kind of variety show which presents us with one essay in the weird and the grotesque after another.

In other words, the movie is not about the hope and the tragedy of man’s search for meaning in the incomprehensible reaches of interstellar space — not even, as Adams’s original creations were, at one remove. Instead it is about the remarkably fertile imagination — Coleridge would have called it the fancy — of Douglas Adams himself. There’s more than just a tribute to the deceased in the final dedication, “For Douglas.” His inventions have given much pleasure to millions of people, but I doubt whether even he, now cruising the interstellar spaces himself — reportedly he was cremated with his towel — would have been quite pleased at the absence from them even of God’s absence.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.