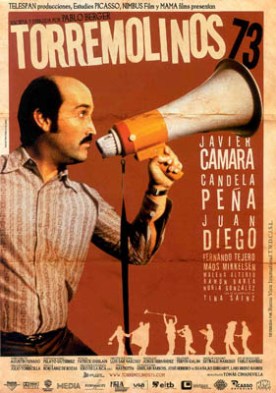

Torremolinos 73

Pablo Berger’s Torremolinos 73 clocks in at only 87 minutes and so gives the impression of having been chopped about clumsily like one of those 1970s-era porn films that are its subject. It’s a shame that he was not allowed to flesh out more of the terrific ideas we mostly only catch glimpses of here, but even as it is the film presents us with a wonderful portrait of the seediness of the ‘70s, post-sexual revolution. This is made all the more piquant by its setting in the dying days of Franco’s régime in Spain. The pornography of that era always managed to convey to people the sense that they were being initiated into a world of sophistication and moral adulthood that their now-discarded moral and religious training had hitherto concealed from them. This effect must have been considerably exaggerated for those who had grown up in the Puritanical isolation of Spain during the Franco years. Likewise, for those who were used to the censorship of the Catholic Church and the fascist government, the equation of “art” with openness about sexuality — remember what the term “art house” used to mean? — must have been particularly seductive.

Yet Berger doesn’t insist on any of this. He is content to allow political and even moral questions merely to lurk in the background of the funny and rather touching human story he has to tell. Alfredo (Javier Cámara) works selling encyclopedias door to door. Or rather attempting to sell them. We watch his hopeless spiel on behalf of Montoya publishing’s ten volume history of the Spanish Civil War bound in leather which comes with a complimentary bronze bust of Franco. Not too surprisingly, Alfredo is not doing well — and not only because the Franco government is on its last legs. In addition, old bourgeois habits of self-improvement are dying out. The latest trend is for handsomely bound encyclopedias to give way to supermarket pamphlets meant to be collected individually and subsequently bound together. Soon they too will go, and with them a whole world of middle class, middle-brow striving and “respectability.”

As one of the last remnants of the old days, Alfredo finds himself desperate even to pay the rent, let alone satisfy the wishes of his affectionate but mournful wife, Carmen (Candela Peña), who desperately wants a baby. But just when things seem blackest, Alfredo’s boss, the wonderfully raffish Don Carlos (Juan Diego) of Montoya publishers suggests a way out. He wants his few remaining encyclopedia salesmen, Alfredo among them, to retrain to take advantage of a deal he has struck with a Danish publisher of sex manuals — ostensibly of a “scientific” or “instructional” character — by shooting super-8 movies of themselves having sex with their spouses. Such is the innocence of the time and the place that no one, not even Don Carlos, seems to imagine any other kind of sex as being possible.

At first Alfredo says absolutely not. “My wife isn’t showing her bits for anybody, not even the Pope,” he insists. But the allure of making 50,000 pesetas, plus bonus, per film proves too strong.

“How many encyclopedias would you have to sell to make 50,000 pesetas?” asks Carmen.

He replies glumly, “154,” with the air of a man who thinks that the number might just as well be a million, since that would be no further out of reach.

Don Carlos assures them that the supposedly the “instructional” films will only be seen in Denmark, through the distribution system that Don Carlos has arranged with Danes, and that they should “Do it for the progress of science.” To help them, he has brought in a Danish couple to show the technologically backward Spaniards how to use the Super8 movie camera. Erik (Tom Jacobsen) makes helpful suggestions to Alfredo about his camera technique while Frida (Mari- Anne Jespersen), obviously a woman of some experience, makes helpful suggestions to Carmen about how to take her clothes off for the camera. When Alfredo has a hard time filming his own lovemaking with Carmen, Erik and Frida offer to let him film them. It doesn’t take long for Alfredo’s embarrassment to overcome by a growing sense of movie professionalism, which is reinforced by Erik’s own sense of pride at having once been, he tells him, an assistant to Ingemar Bergman.

Soon Alfredo grows dissatisfied with the little vignettes he is filming of himself with Carmen dressed as a nurse or a soccer player or a beauty queen. A showing of Bergman’s Seventh Seal on TV inspires him to write a screenplay for a proper movie, which he calls Torremolinos 73 — a Bergman pastiche about a young widow who comes to a Spanish resort and encounters a pale lover dressed like Death who reminds her of her husband. Meanwhile two things are happening. Unbeknownst to Alfredo, Carmen has become a superstar of Danish pornography, recognized in public by vacationing Danes who ask for her autograph. Also, now that they are relatively affluent she becomes more determined than ever to have a baby. But when they are tested it is found that Alfredo has a sperm count of zero. Adoption seems out of the question because their moral character will have to be investigated and it will take years anyway.

To Alfredo’s surprise Don Carlos likes Torremolinos 73 and offers to finance the film. He, Alfredo, will direct — though a Danish crew is to be brought in to help him — and Carmen is to star as the widow. A strapping young Dane called Magnus (Mads Mikkelsen) who is suspiciously eager to meet Carmen is to play Death. Alfredo happily sets to work recreating his wintry Scandanavian scenario in black and white — including Death on a carousel, dwarfs in fancy dress and Carmen looking into what turns out to be her own coffin — in the all-but-deserted but way-too-colorful resort of Torremolinos without particularly noticing its own Bergmanesque quality.

But Don Carlos wants to make a few small changes in the script, and Alfredo’s eyes are at last opened to the fact that, to him and the Danes, Torremolinos 73 was all along just comically pretentious pornography. Even more alarming is the fact that at the same time he realizes the film is something else again to Carmen. He has written a film about death as a surrogate husband because it sounded Bergmanesque, and that’s what film-making means to him. But in doing so he has unwittingly provided a surrogate husband for his own wife. In the end, both he and Carmen have learned the lesson taught by pornography: that sex is a commodity to be used to get what they want. Yet Berger is able to make the rather facile ending an upbeat one because the couple have found that among the things they didn’t want after all is one that they still do. It’s too pat and probably the result of having to cram everything into 87 minutes, but everything up to that point is remarkably fresh, intelligent and well-worth seeing.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.