Star Turns

From The American SpectatorSummer blockbuster season is a good time for reflection upon the essential ephemerality of the movies, or at least of most movies. I didn’t see the latest and, it is to be hoped, last instalment of the Star Wars saga because I found watching the two previous ones far too painful an experience. Here, I thought with growing embarrassment, was obviously a phenomenon of the 1970s which had long outlived its moment of cultural vitality. Those of us who remember the post-Vietnam era will also remember the excitement with which many of us greeted the original Star Wars — now crazily demoted to “Part IV” of the amalgamated narrative and renamed “A New Hope” — because it had found a way to re-imagine the classic movie hero and in the process to remind us of what a large part of our movie-going experience, which was in the process of becoming quite a different thing in the 1970s, had once involved seeking images of heroism.

At the time it didn’t matter so much that the movie ducked all the hard questions by setting its action in outer space, or on non-existent planets, and amidst non-existent species. The inhuman semi-robots and weirdly-shaped space ships mown down in such gratifying numbers by Luke and Leia and Han Solo — all of whom were themselves unmistakably our contemporaries, 1970s-vintage American kids — were as morally unproblematic and undemanding of our sympathies as the Red Indians had been back in the heyday of the Western or as movie-Nazis still were — and indeed still are in the form of neo-Nazis. Thank you Adolf for supplying us with the villains we never get tired of. True, Luke and Leia and Han were just the tiniest bit vapid, but any doubts we might have had about their finer qualities were smothered by our sense of gratitude at the idea that heroism might continue to exist at all.

These feelings of excitement and gratitude began to pall even in the early sequels, now known as Parts V and VI, The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and The Return of the Jedi (1983). The self-referential quality characteristic of post-modernism — which gives us movies based on other movies rather than on real life — was already becoming too familiar, too cloying, too unreal for anyone over the age of about 12 to take these movies seriously. By the time we got to the new Episode One, The Phantom Menace (1999) with its ghastly Disney-bred monster, Jar Jar Binks, and its pre-pubescent, video-game-style heroes, Anakin and Padmé, the accumulation of po-mo irony had reached such toxic levels as utterly to annihilate any lingering sense of the heroic in the ever more confusing and ever less believable narrative. In other words, Star Wars had its one and only cultural moment in 1977. Its inferior sequels continue to generate their millions and their hundreds of millions for George Lucas partly, I think, because the movie audience is so much younger and less discriminating even than it was then and partly because so many people are so desperately hoping to get once more what they got from the original. They can’t allow themselves to admit that the magic is gone and the glory is departed.

In the era of the DVD, when the whole of cinematic history is available to us, we can be particularly alert to the ways in which movies date, and one of the most interesting of these is in their politics — which, at least since the 1960s, have always been liberal but always smacked of the liberalism of the moment. Consider the anti-war message of The Revenge of the Sith which reportedly has the budding Darth Vader saying “If you’re not with me, you’re my enemy” — a statement supposedly but not actually the equivalent of President Bush’s unremarkable, even tautological statement that, as I understood him, those who were unwilling to fight terrorism will thereby help the terrorists. “The parallels between what we did in Vietnam and what we’re doing in Iraq now are unbelievable,” commented the pin-headed Mr Lucas with more truth than he knew. Yet if you look back to a movie like Air Force One of 1997, what do you find? There the one-time Han Solo, Harrison Ford, has become the President of the United States and is full of apologies to the rest of the world for — you’d never guess it — not doing enough to fight terrorism and waging war against it “only when our own national interest was threatened”! Now, he says, America must “never again allow political self-interest to deter us from doing what is morally right.”

Oops! That was then, when Bill Clinton was President and preparing to rattle a sabre or two in the direction of the wicked Serbs and perhaps others who went about doing evil in far away countries of which we knew nothing. Then the Republicans were at least tempted by the “realist” tendency to disregard questions of morality in favor of a rather narrow conception of the national interest. Meanwhile Clinton represented the do-gooding internationalism of Woodrow Wilson and Jimmy Carter, which had once dreamed of putting the world to rights — though in Carter’s case it had done little but dream. And preach. And hector. Nowadays it’s the Bush administration who are the new Wilsonians while the Democrats are insisting that the moral case against Saddam Hussein had nothing to do with our national interest, that which alone could provide any justifiable reason for going to war.

Of course it is hardly surprising if Hollywood moralism follows every twist and turn of the Democratic party line, since it is almost a pre-requisite of membership in the tightly knit film-making community to offer reflexive support to the Democrats. But it is often uncanny how quickly Hollywood responds to the latest Democratic talking points. Just look at Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven. This cannot have been less than years in the making, and yet it appeared on our cinema screens in May virtually simultaneously with the climax of the Democratic campaign to marshall every resentment against conservative judges, restrictions on stem cell research or abortion or bans on gay marriage to portray Christian believers as being, like every single bad guy in the movie, dangerous fanatics.

The crassness with which Scott’s movie made its point that only atheists, agnostics and (maybe) Muslims could be decent human beings while all the evil in the world was the result of Christian zeal may have been responsible for the fact that it bombed with the great American public, disappearing from among the Box Office Top Ten before it had grossed a measly 50 million dollars. Yet it did a beautiful job of illustrating and making explicit for the masses the proposition which as yet the Democrats had only been able to hint at, namely that people who took a traditional Christian view of morality, especially sexual morality, were the next thing to lunatics and ought to be rigorously excluded from the federal bench — or indeed any other office of trust and responsibility.

|

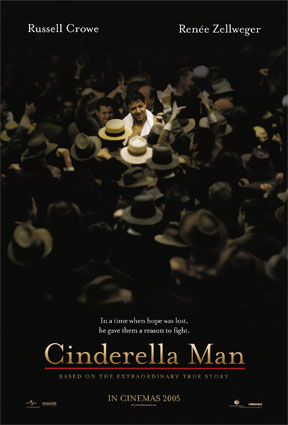

It is hard now to say what people a few years hence will think about such topical political correctness, but I predict that it won’t wear well. In fact, nothing does but the good old themes, one of which was tapped into by the first Star Wars in its portrayal of simple heroism. In today’s movie climate, heroism still looks so old-fashioned as only to make sense to us in the distant future, which may be why the hero of the Movie of the Month, Ron Howard’s Cinderella Man, though an actual person who lived in the 1930s, looks as if he were from another planet. Russell Crowe plays James J. Braddock who defeated Max Baer (Craig Bierko) for the heavyweight boxing championship in 1935 and was called by the sporting press of his own day the “Cinderella Man” because he had been out of boxing and working — when he could get work — on the Jersey docks when suddenly he made his spectacular comeback. It was and is a great story, but Braddock’s personal and moral qualities weren’t unique, as Mr Howard’s film tends to make them seem. Back in the 1930s, in other words, heroism didn’t look like something from a galaxy far away.

Regrettably, Mr Howard doesn’t do quite enough to establish the social milieu of the Great Depression, or to show that the qualities of courage, honesty, patience in adversity and hard work were also present in a great many persons who never climbed into the ring with a fearsome opponent or became rich and famous as a result of doing so. To be truly heroic, I think, heroes should not be alone in their heroism. Roland needs his Oliver, Launcelot his Gawain and Luke his Han Solo. But as with the original Star Wars, we must be so grateful that a Hollywood product offers us heroism of any kind that it would be churlish to dwell on the movie’s shortcomings instead of celebrating it for what it is, which is the best Hollywood movie of the year to date, and the one most likely to last.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.