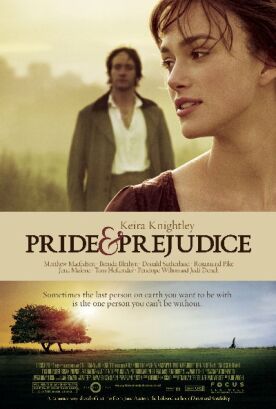

Pride and Prejudice

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice is a great novel partly because it tells a good human and romantic story which is also the vehicle for profound moral reflection. Pardon me if that sounds too obvious to need saying. I would have thought so too. But Deborah Moggach who wrote the screenplay for and Joe Wright who directed the new movie version of Pride and Prejudice appear to have forgotten it. They have given us the human story all right, suitably amped up for the big screen. I am not one of those who thinks that Keira Knightley is too pretty for the role of Elizabeth Bennet, and her star-power is a definite asset — that of Matthew MacFadyen’s Darcy somewhat less so. Add to the beautiful set of her jaw a quantum of lush photography and soaring emotions and you have a lot to work with, but the film-makers have left out the moral dimension altogether. The result is a badly unbalanced if visually impressive film that ends up being a vulgarization of Miss Austen’s novel.

When I say they have left out the moral dimension, I mean they have left out the morality that Jane Austen would have understood and that, naturally enough, she put into the novel. But the film substitutes for it a typically Hollywoodish moralism in the form of an implied critique of Regency England’s social order. It is important to understand that this is desperately unhistorical. It’s true that the first social critics as we recognize them were around at the time. In particular, the French Revolution had spawned revolutionaries in England like William Godwin and even feminists like Mary Woolstonecraft. But Jane Austen was not such a social critic, given to glib formulations about “society” and its shortcomings. She was utterly at home with her society and with its morality and accepted it as her own. The novel is in fact on one level a kind of taxonomy of moral types according to the categories generally accepted at the time. The whole point of Elizabeth Bennet’s initial rejection of Mr Darcy has to do with a deficiency of manners which she loudly proclaims to his face without realizing that her own moral judgment is to be faulted for being too hastily arrived at.

You won’t understand any of this from the film. It is clear that its Elizabeth doesn’t like Mr Darcy at first, but this is only because of his behavior to her and her sister and not because he has fallen short of a more generally implied social standard. She is also under a misapprehension about his behavior toward Mr Wickham (Rupert Friend), whom she likes. But that there might be anything more than personal preferences and real or imagined personal slights in all this the film gives us no hint. Jane Austen’s Elizabeth disapproves of Darcy not just because he is disagreeable to her but because he has behaved in a way that she and her society believe is objectively wrong. The fact that, two hundred years on, it is considered tasteless and tactless to be so “judgmental” about people does not mean that you can just leave all that kind of thing out and still imagine that you have anything more than the hollowed out shell of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

The film’s own morality is also rather an annoyance.You may not have heard about it before, but back in those days there was a lot of sexual repression about. In fact, it was everywhere! The new film’s authors think it important for us to be reminded of this from time to time with shots of a pig’s testicles as he wanders into the Bennet family’s parlor, or of the extraordinary collection of nude paintings and frescoes and statuary thoughtfully pored over by Elizabeth Bennet on her visit to Pemberley after her rejection of Darcy’s proposal. Her obvious regret and heart-ache as she looks first at the racy images and then at a bust of Darcy suggest, absurdly, that she doesn’t know whether it’s missing out on him or the sex that she most regrets. Likewise, the emphasis given to the preemptive self-defense by Charlotte Lucas (Claudie Blakley) for agreeing to marry the awful Mr Collins (Tom Hollander) smacks of an inappropriate and anachronistic feminism. “I can’t afford to be romantic,” she says, conveniently forgetting that Elizabeth can afford it no better than she, though she is so far “romantic” as to refuse a man whom she thinks she cannot love anyway. Charlotte doesn’t quite blame the patriarchy for making her accept Mr Collins’s proposal, but that or something like it is implied for today’s audience. The giggly girlishness of Jane (Rosamund Pike) and Elizabeth as well as their younger sisters is also an implied critique that is nowhere in the original.

“Don’t you dare judge me,” says Charlotte, just as if she had never noticed that in the world she supposedly inhabits people “judge” each other all the time. It is expected of them, just as they themselves expect to be judged. As a result of the omission of this vital element of the novel, we don’t have enough of a sense of the social context in order to understand how it is that the family consider themselves “ruined” when Lydia (Jena Malone) elopes with Mr. Wickham — or how Mr Darcy saves them from ruin by paying off Wickham. “This is grave indeed,” says Darcy at the news, but we just have to take it on trust. A similar lack of context leaves us unsure whether Darcy’s mention of a “lack of propriety” in Elizabeth’s mother, sisters and even her father — who, by the way, is portrayed by Donald Sutherland as a virtual dotard — is meant to strike a chord with us, as it undoubtedly does with Elizabeth. Or is it just Darcy being tactless and arrogant? With Jane Austen, you always know, too, that personal fulfilment only comes through the faithful application of the moral principles that are upheld by the dominant culture. Without any such culture of our own, and little idea of what it might look like even if we had one, how can we even properly feel what the human story invites us to feel?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.