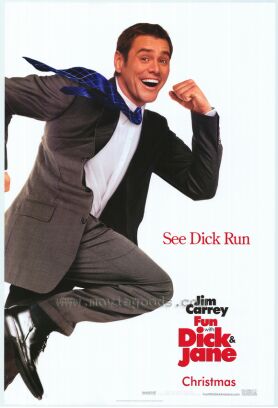

Fun With Dick and Jane

A new thing, in the movies as elsewhere in life, is a rarity, but I think I’ve stumbled on one. It is a new genre which we might call paranoid comedy. Paranoia is of course rife in Hollywood, and paranoid documentaries, thrillers and political dramas are now almost the only kind there are. But until now comedy has remained mostly immune from its corrosive effects. No longer. At least not to judge from Fun with Dick and Jane. Superficially this film resembles other sympathetic treatments of middle-class criminals, not least its original version, starring George Segal and Jane Fonda, of 1977. But where economic conditions in 1977 were at least fairly grim, today we are approaching what economists call “full employment.” Why are this Dick (Jim Carrey) and Jane (Téa Leoni) turning criminal? That’s where the paranoia comes in. This film attempts to persuade us that, because virtually all the rest of the world is criminal, or complicit in crime, or else powerless to do anything about it, its heroes’ criminality is inevitable and justified. In the end they mete out a sort of vigilante justice as a way of empowering themselves against the vast and terrifying forces arrayed against them.

It’s not an obvious recipe for comedy, though it can’t entirely keep out the laughs owing to Mr Carrey’s energetic mugging. His character works for a giant corporation called Globodyne which — but need I say more? We know already from all the other paranoid movies that nothing good is going to come to Dick from the giant corporation that employs him only to take advantage of him — though, rather oddly it might seem, Dick himself doesn’t know it. Yet. On the contrary, he thinks he’s in clover because he’s just made vice president for communications of Globodyne. On the strength of his promotion, he suggests to Jane that she quit her job to spend more time with their son, Billy, who has spent so much time with his nanny that his native language appears to be Spanish. Nobody does boyish innocence — albeit boyish innocence now long since prolonged into middle age — better than Jim Carrey, though his little dances and songs of triumph at his promotion are laying it on a little thick, maybe. Of course, the more he rejoices the more certain we are of what is to come.

Globodyne’s c.e.o., Jack McAllister (Alec Baldwin) and c.f.o., Frank Bascom (Richard Jenkins) send the new v.p. on a TV show called “MoneyLife with Sam Samuels” to talk about the company. There he is ambushed with questions about highly embarrassing financial shenanigans on the part of McAllister and Bascom about which he clearly knows nothing. We watch as poor Dick stammers and stumbles his way through the show while in a corner of the screen a graphic of Globodyne’s stock price plunges towards zero. Why would his bosses set him up like this? What did they stand to gain from his and the company’s embarrassment and the sudden collapse of its stock? Even more puzzling, how can it be that it is Dick who is said to be under threat of indictment for his part in a crime which he has just given the world such a spectacular demonstration of knowing nothing at all about?

But that’s paranoia for you. McAllister gets off scot free with the $400 million he has looted from the company while Bascom gets a light, 18 month sentence and a $10 million pay-off for keeping his mouth shut. Dick, meanwhile, becomes the patsy because, well, because he’s sweet, funny, innocent Jim Carrey, a man born to be a (movie) patsy. There is more paranoia in Dick’s inability to find another job when Globodyne goes out of business. In the real world the economy may be humming along nicely, but in the world of Hollywood paranoia it’s always the 1930s and Dick and Jane’s only choices are eviction and the soup kitchen or a life of crime. Of course there is the third alternative of a job at Wal-Mart — sorry, that’s Kost-Mart here — but Dick, after giving it a brief try, prefers indigence, homelessness and the chance of prison when he turns to crime. As anybody would.

And so another left wing political base is touched as another giant conspiracy to impoverish the world is uncovered by the way. Likewise, the close credits offer ironic thanks to Enron, WorldCom, ImClone, Adelphia etc. as a way of reinforcing the message that everybody in the corporate world is doing it, and doing it to us, or our surrogates, Dick and Jane. Interestingly, the one exception to the rule that there are not, for most of us when we are job-seeking, hundreds of applicants for every position is the profession of acting. There there really are demoralizing mobs of people up for every available part, as there apparently are here even for the kinds of executive jobs that Dick is applying for. This fact just might help explain how it is that we are getting a movie about the evil rich from a guy making $20 million or more every time he steps in front of a camera. For someone who has experience of the precarious living to be made as an actor is more likely to think he has earned success when it comes, and to look with contempt on the corporate types who all get rich, as it must seem to him, without running anything like the same risks. It’s more paranoia, of course, but at least it is a bit more understandable paranoia than that on offer in this oddly unreal though not always unfunny comedy.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.