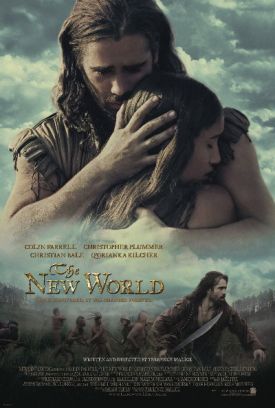

New World, The

Those who are as old as I am may remember being young in 1967 when Bo Widerberg’s Elvira Madigan made such an impression on us impressionable youths. Up until only a few years ago, and maybe still, for all I know, you couldn’t buy a record, cassette or CD of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21, K. 467, without seeing images from the film and reading the notice that its now-familiar slow movement made it the “Elvira Madigan” concerto. Terrence Malick was 24 in 1967, and the movie must have made a big impression on him too, for now in his 60s he has brought out a new movie, The New World, in which he has chosen to portray the first arrival of the English in what was to become the United States through Widerberg’s lens and Mozart’s music.

To be sure, he’s made a couple of changes. He’s jumped 21 Köchel numbers to No. 488 to give us the slow movement of the 23rd Piano Concerto as the accompaniment to his lovers’ dalliance in the forest. And he alternates it with a passage, almost as often repeated, from the Prelude to Das Rheingold by Richard Wagner that is meant to suggest momentous discovery. Oh, and instead of making the lovers choose, tragically, to stay together, he makes them choose, tragically, to split up. It doesn’t matter. Either way, the message is essentially the same as Widerberg’s. As Captain John Smith (Colin Farrell) says in one of his endless interior monologues, rendered in voiceover, “There is only this” — meaning idyllic sex with Pocahontas (Q’Orianka Kilcher) — “all else is unreal.”

Well, not as such. Once he’s back among the English he changes his mind. “It was a dream,” yet another voiceover monologue tells us. “Now I am awake.” Later, he comes to regret this flip-flop, and when he meets Pocahontas again in England, long after they have split up and she has married John Rolfe (Christian Bale), he tells her: “I thought it was a dream, what we knew in the forest, but it’s the only truth.” Except, of course, that it’s all a lie and nothing remotely like it happened or could have happened in fact. But say that it did. Even Elvira Madigan knew better than to suppose that making love in the forest was the only truth. There was also that other truth, the truth of work and family and responsibility on which the two lovers deliberately turned their backs. They knew they were opting for unreality, in other words, where Captain Smith, like Terrence Malick, seems more than a little confused about where reality actually lies.

All they know is what they want to believe. And this also comes across in what turns out to be little more than the incidental “encounter” of Old and New Worlds. You’d think this was an important enough historical event for the film to be about it, as the title seems to suggest. But it’s not. Instead, “the New World” turns out to lie within us — now there’s an idea no one can have thought of before — and what is arguably the most momentous discovery of the last thousand years is turned into the backdrop for a love story. Perhaps because it is only a backdrop, and because the reality he is focused on is an interior one of thoughts and feelings, Mr Malick thinks that he has no obligation to historical reality. At any rate, insofar as there is any of the historically New World in this movie it is a hippie fantasy rather than the real thing.

The Indians, so far as we see them, never work. They take their ease and play all day, apparently, while living in peace, harmony and plenty. Meanwhile the settlers work and slave constantly and yet are reduced to eating shoe leather and each other. The latter seem to have no idea of hunting, fishing or agriculture and to be utterly dependent on getting game and corn from the Indians — or supplies from England. They are only interested in searching for gold, even if they starve in the attempt, and in fighting each other. Similarly, the Indians are all attractive graceful, well-proportioned and handsomely decorated with tattoos, like Allen Iverson. The English are all dirty, ugly, toothless and bedraggled, or all of them except the obviously Irish Captain Smith, and their gold-lust — or is it God-lust? — makes them hate-filled, vicious and constantly at one another’s throats.

This easy schematization of complicated events only increases the basic incoherence at the heart of the movie. When Smith is saved from death by Pocahontas — who, by the way, is never named in the film until she is re-named Rebecca — he is presented with a stark choice: live the hippie life in peace, plenty and sexual freedom among the Indians or go back to the English settlers and return to a life of nothing but hardship, treachery, bitterness and celibacy. Which would you choose? Why Captain Smith goes back remains a mystery, as is his subsequent jilting of Pocahontas when it looks as if he could have her without going native. But Mr Malick has little time for linear narrative and questions of motivation and plausibility. His film is organized as a series of tableaux vivants to which we must supply our own context. Even the rescue of Captain Smith by Pocahontas’s throwing herself upon his body is not portrayed except in its aftermath, as the bodies are all tastefully arranged. Mr Malick seems to have a positive distaste for action.

Likewise, in the battles between the English and the Indians, the latter always appear to be getting the better of the former, but all is chaotic and aimless and impossible to make any sense of militarily. There is just a series of pictures. Watching them you feel as if you are trying to make sense of a book in a language you don’t understand from looking at the illustrations. Drama is also purged from the dialogue. There is more voiceover, meant to be seen as interior monologue and even prayer, God help us, than there is verbal interchange between the characters. Moreover, long passages of Indian speech are not subtitled, though shorter ones sometimes are. Pocahontas is soon speaking English like a native, but none of the English, even Captain Smith, appears to speak the Indian language. And Pocahontas’s English is more often employed in voiceovers — you mean she’s already thinking in English? — and solitary prayers to the Great Spirit, or “father” or “mother” or sun or moon — than in communicating with the English. When Rolfe comes on the scene, blow me down if he doesn’t start in on the voiceovers.

The result is that the characters are as detached from the drama of their own lives as we are, always ruminating about their feelings rather than living, and lead an unreal, almost disembodied existence. The love story, instead of bringing us closer to the almost unimaginable strangeness of the world inhabited by settlers and natives alike four hundred years ago, actually makes it more unreal and incomprehensible. This is a film, like Elvira Madigan, with lots of pretty pictures and lots of pretty music, but the world it portrays goes back only 40 rather than 400 years. It is New only in the sense that it is Mr Malick’s own.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.