On Sex and Violence

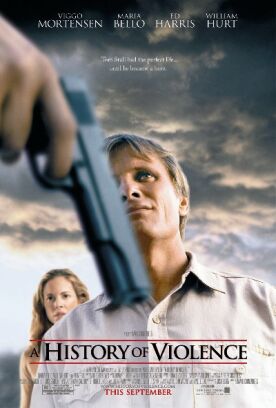

From The American SpectatorIt has never quite struck me before, but the extent to which we link “sex and violence” in our discussion of the cultural impact of television and movies must have something to do with the fact that sex and violence are, or have been at various times, the same kind of thing — that is, the kind of thing that is a natural part of life but about which, for one reason or another, we have taught ourselves to feel deeply ashamed. One measure of that shame is to be observed in David Cronenberg’s movie, A History of Violence, in which Viggo Mortensen plays Tom Stall, a man who becomes a hero in his small Indiana town by single-handedly taking on and killing two villains who are trying to rob the diner he owns and manages.

Commendably, Mr Cronenberg does not allow us the moral luxury of wondering whether or not Tom over-reacted, since he has earlier shown us the bad guys in the course of another robbery gratuitously murdering, without hesitation and without compunction, a motel manager, a maid and a little girl. We already know, in other words, what Tom has to intuit in a split second as he sees one of the bad guys pointing a gun at and threatening a waitress — namely that not only the waitress’s life but his own and those of the four other people in the diner are at stake. Accordingly, when in a series of lightning moves he disarms the other gunman and then shoots them both, we are meant to see Tom as being as much a hero as do his friends and neighbors and the TV audience before which he is subsequently lionized.

At the same time we are made aware that Tom’s teenage son, Jack (Ashton Holmes) is being bullied at school. Jack is a budding intellectual of fashionably melancholy disposition, and he parries the insults of the Bobby the Bully (Kyle Schmid) with wit, but there is no doubt in our minds or his own that he has backed down from a confrontation. After his father’s feat of courage, however, and perhaps inspired by his example, he decides to fight back — and in doing so beats Bobby so badly that he has to be hospitalized. Jack is suspended from school and the parents of the injured boy threaten to sue Jack’s family. Tom, when told of the incident, naturally assumes that the occasion requires him as a parent to administer some verbal correction, and he says to his son, “In this family, we do not solve our problems by hitting people.”

With typical teenage insolence, Jack replies, “No, in this family we shoot them!” — whereupon his father slaps him across the face. It’s a funny moment, pointing us towards a familiar hypocrisy of our times when it comes to violence, but it also reminds us that where there is hypocrisy there is also shame. Tom and Jack and those of us who are encouraged by David Cronenberg to admire them both all feel a sense of shame at having to solve our problems by hitting — or shooting — people. Culturally, we have taken to heart Hannah Arendt’s mysterious pronouncement in On Violence that “violence can be justifiable, but it never will be legitimate.” Huh? Come again? If it’s justifiable, how can it not also be legitimate? I think that what she meant was that it can sometimes be OK for us to be violent — as it obviously was OK for Tom Stall — but that if we commit an act of violence, however justified, we’re supposed to feel sad and ashamed about it. In other words, the happy warrior is no more. Now the warrior had damn well better be miserable and suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or we’ll know the reason why not.

Mr Cronenberg also makes what ought to be the obvious connection to sex which, at least in the Christian tradition, is something else that we are meant to feel ashamed of enjoying too much. Tom’s various acts of violence in the film — which makes the point that violence can easily become habit-forming — are obviously a turn-on not only to himself but also to his handsome wife, Edie (Maria Bello), who is so sexy that it is likely to become a turn-on to the audience as well. Violence, you see, is displaced sex, as every amateur Freudian in Hollywood knows. And if you believe that favorite cliché of the foreign journalist and intellectual — a cliché which appears to have an almost mesmeric power to paralyze the judgment and simple observational powers of so many Americans belonging to my own, “Baby Boom” generation — namely that America’s is “a violent society,” then the answer to the implict problem is obvious: we’re not having enough sex.

Mr Cronenberg, a Canadian, at least takes the trouble to make this highly dubious proposition somewhat plausible. The Danes, Lars Von Trier (writer) and Thomas Vinterberg (director) don’t bother. Mr Von Trier in particular, has made rather a career out of slandering a country he has never visited in movies like Dancer in the Dark and Dogville. So confident is he in Dear Wendy of an audience of intellectually upwardly mobile Americans eager to believe the worst of their own society that he feels he can take the violent-America paradigm for granted. The “Wendy” of the title is a hand-gun belonging to the young hero, Dick Dandelion (Jamie Bell). Dick forms a gang called the Dandies which is united by feelings of erotic attachment to their several sidearms and which ultimately engages in a Columbine-like atrocity. The setting of these events, though supposed to be in a coal-mining region of America, is so obviously not America — or any place else on planet Earth — that you’ve got to wonder at the gullibility the film-makers feel entitled to assume in their audience. Or are they, by an amazing stroke of irony, actually ridiculing the sex-and-violence connection they are ostensibly promoting? No, probably not.

In these circumstances, The War Within and Paradise Now, two movies in recent weeks which might otherwise have shocked us by being apologies for jihadist suicide bombers come almost as a relief. At least these guys aren’t all gloomy and miserable about their prospective violent acts, which they view as martyrdoms, or inspired by the thought of them to some rough sex with comely and willing maidens. On the contrary, both murderers are presumably saving themselves for the 72 virgins that are to be their reward in the Islamic paradise, and so they turn down some pretty attractive opportunities while strapping on the gelignite here below. “What happens — afterward?” one of the bombers in Paradise Now asks his minder.

“Two angels will pick you up.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

I’m guessing that the humor here is unintentional. But are these guys really so puritanical? Didn’t Mohammed Atta visit a strip bar before taking down the twin towers? There’s the cultural tip-off. Western culture has learned to overplay the sexiness of violence, while Middle Eastern culture just as reliably underplays it. I guess it all has to do with how our heroes wish to be seen. The Western hero wants to appear as a victim, a sufferer from the mental anguish of remorse but nevertheless the devil of a fellow with the ladies. The Eastern hero still wants his heroism uncluttered by any such stray evidences of human weakness. It’s all a matter of taste, really.

Never is this clearer than in Jarhead, yet another foreigner’s take on American violence. For though Anthony Swofford, on whose memoir of his service with the Marine Corps during the Gulf War of 1991 the film is based, is American, he has been carefully schooled by an overdose of creative writing courses to suck up to those same elegantly literary and European ideas of The Trouble With America that we see in the work of Messrs Von Trier and Vinterberg. As a result, he has found a fashionable English director, Sam Mendes (American Beauty), with nearly as distorted a view of this country as Mr von Trier’s to make Jarhead into a movie. You may not be surprised to learn that Swofford’s and Mendes’s marines are seething cauldrons of frustrated lust who can hardly wait for the opportunity to blow away a few A-rabs. I wonder if the two things could be somehow connected?

It seems odd to me that film-makers and the media in general can still treat sex and violence as dark and shameful secrets when they themselves have been portraying little else for decades. Wouldn’t it be more interesting were they to rip the veil from something which really has been kept out of sight, at least in the movies, for a long time — things like, honor, patriotism, nobility and self-sacrifice? What a shock that would be, to find American fighting men portrayed in those terms, which are now reserved exclusively for terrorists like the heroes of The War Within and Paradise Now. But then there wouldn’t be any job for intellectuals like David Cronenberg, Lars von Trier, Anthony Swofford and Sam Mendes to do, and in doing to show us the penetration of their own intellects.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.