Spielberg Stress Disorder

From The American SpectatorWhen I last wrote in this space I hadn’t yet seen Stephen Spielberg’s Munich, but when I did I found that I had already written the review of it. For in “On Sex and Violence” I had described for The American Spectator’s readers the characteristic Hollywood view of violence before I knew that Mr Spielberg was about to create a such a lasting if unattractive monument to it. To recap, an industry which owes so much of its revenues to the sale of images of violent acts has learned to think of those acts as something both necessary and shameful. There are exceptions to the shame-imperative — certain acts of violence which are allowed to carry no moral or honorable qualifications — and to these we shall return presently. But nearly always the sympathetic movie hero must pay for his violent acts with agonies of conscience and with one or more of the psychological and physical symptom-sets — including insomnia, nightmares, paranoid behavior, drug or alcohol abuse or addiction, suicide, or criminal behavior — that now go under the collective and clinical name of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or PTSD.

PTSD was an ailment unknown to medical and psychiatric science until about 30 years ago when its first appearance in psychiatric handbooks, partly at the instigation of psychiatrists like Robert Jay Lifton who had been prominent in the anti-Vietnam War movment, had an unmistakable political dimension. Large numbers of psychologically damaged veterans were prima facie evidence (if evidence were needed) for the evils of the military and diplomatic policies that had created them. Previously, “shell shock” or “battle fatigue” had been a recognized affliction of men who had had an immediate and adverse mental reaction to combat. PTSD was different in that it could afflict even those who had seen no combat but who were merely made anxious by being in close proximity to it. Also, it could and usually did pop up years later in men who had seemed to be unaffected by traumatic experience at the time. At one point, in 1990, the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study concluded that fully half of those who had served in Vietnam in both combat and non-combat roles were suffering from at least “partial” effects of PTSD.

Now whatever may be the truth of such diagnoses — and some of those who are better qualified than I to assess them tell me that there are a great many reasons to doubt them — there can be no doubt that there are strong incentives for the sufferers to seize upon them as descriptions of their own condition. Not the least of these was the chance afforded those whose military careers were otherwise undistinguished to identify themselves with the victim-heroes featured in virtually every movie Hollywood produced about the war — from Coming Home to The Deer Hunter to Apocalypse Now to Full Metal Jacket to Platoon and beyond. By now, so familiar a figure is the victim hero, tortured by his “demons” for what he has seen and done as a soldier, that he is retrospectively showing up in every other war that finds its way onto the big screen including, inevitably, the war in Iraq. The predicted flood of sufferers from PTSD among returning veterans of that war — the army’s Surgeon General last summer put the figure at 30 per cent — will be met with a flood of movies whose heroes are sufferers from PTSD. But who is reacting to whom, exactly? When Hollywood glamorizes the conscience-stricken vet, is it not reasonable to suppose that the numbers of conscience-stricken vets will increase?

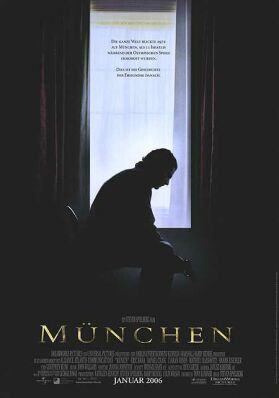

The movie business has always been dependent on the artful marketing of clichés and stereotypes, and it takes decades for most of them to run their natural course and become recognized as clichés. Take the strong, silent type of hero typified by Gary Cooper, the anti-type of the fashionable PTSD-sufferer. He held sway right through the silent era and into the 1950s before turning into a joke — and, not coincidentally, into his opposite. I wish I could say that this agonized successor were now approaching the end of his tenure of the public’s affections, but Mr Spielberg’s routinely suffering hero suggests that it is not so. Eric Bana plays the semi-fictional Avner, chosen by the Israeli government and Golda Meir (Lynn Cohen) in person to avenge the murder of 11 Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics by assassinating an equal number of those who were thought to have been involved in that terrorist operation. Mr Bana struggles with his illness, apparently, only for a single night. But in that night he runs the gamut of symptoms from nightmares to substance abuse to paranoid anxiety so that, in the morning he is ready to abandon not only his highly secret mission but all connection with the state of Israel.

Forgive the spoiler, but it turns out to be crucial to Avner’s self-esteem that he should be able to continue to think of himself as better, purer, more civilized and more righteous than the people he has undertaken to kill. Though you might not have expected it, he has thoroughly absorbed the Hollywood view of violence, which is that killing terrorists is an act morally equivalent to the terrorist acts which are being avenged. Fortunately for Avner, he learns to think well of himself once again, secure on his morally superior perch because, even though he believes he has done deeds morally indistinguishable from those of the terrorists, unlike them he feels really bad about it afterwards. Thus does PTSD provide both him and Mr Spielberg with what remains in their own eyes a morally unassailable excuse for the violence they have to offer. Indeed, violence without such an excuse has become almost unknown in Hollywood unless it can claim the alternative but equally unanswerable moral defense that it is directed against Israel, the Nazis, sexually abusive men, white racists, corporate fat-cats or the United States of America and its citizens. It is now not possible to represent a cinematic killer of Islamic terrorists without his little treasury of neuroses, but no one seems to mind sympathetic portrayals of the terrorists themselves, as we learned from The War Within, Paradise Now and Syriana, all of which opened last fall.

The last-named flick is worth particular notice because of the number of political clichés it manages to cram into its slightly more than two hours — not only, that is, a sensitive, soulful and sympathetic suicide bomber and PTSD as suffered by its two main heroes, played by George Clooney and Matt Damon — one of them the victim of bereavement through an accident whose only purpose is to make him a victim — but also a couple of venerable old clichés that, one would have thought, were done to death back in the 1970s. These are a secret and corrupt alliance between the U.S. government and a multinational oil corporation and a rogue CIA untethered by moral or legal restraint making violent mischief wherever in the world it shows its ugly American head. It takes a certain amount of blinkered self-absorption to make a film about terrorism in the first decade of the 21st century whose bad guys are the same old corporate chieftains and rogue CIA agents who have been busily filling those roles in movies going back 30 years and upwards, but Hollywood showed that it was up to it a year earlier in its risible re-make of The Manchurian Candidate. When Hollywood thinks of political or military matters, it’s always 1974. Can it be that they actually don’t know we’re now governed by neo-Wilsonians, busily trying to export American-style democracy to the unfree world?

|

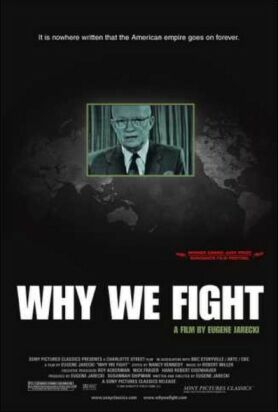

Yet even such undying — or at least undead — paranoid fantasies as Manchurian Candidate and Syriana pale into insignificance next to Why We Fight, Eugene Jarecki’s much heralded attack on the Military Industrial Complex. The what? Those of you who, like me, can remember the Vietnam era will recall what a workout that particular boogeyman got in the late 1960s and 1970s. It was a paranoid’s dream come true: a vast and impenetrable bureaucracy whose very existence made bad things happen all over the world. Serious discussion of political and military matters ground to an instant halt the instant the Military Industrial Complex was mentioned. It was by definition that of which we could know nothing directly, except for the evil effects it caused. In the years since the 1970s, the left has of course retained its hostility to the Pentagon and defense contractors, but the looniness of attributing American foreign policy decisions — which, however mistaken, always had a serious rationale of their own — to the mere desire to keep the Pentagon and defense contractors in business was mostly held in check. No more. The cranks are out of the closet again, and Hollywood is only too happy to offer them a forum.

And for the same reason that Hollywood believes in the mystery of “violence.” Because both “violence” and the Military Industrial Complex are self-sustaining systems, vast impersonal forces that you have to be an intellectual to understand. Let the proles and the peasants blame terrorism on terrorists; if you’re an intellectual — like, say, a college professor — or, more importantly, a would-be intellectual — like, say, a Hollywood film actor, director, producer, or writer — you will be inclined to take it for granted that blame lies in secret places that only clever fellows like yourself have the wit to discover. This pride of intellect is even more likely to be gratified, of course, if it is able to demonstrate to its own satisfaction, as Mr. Jarecki does, that the simpletons who are prepared to engage in violence against terrorism and who erect vast Military Industrial Complexes to that end are themselves to blame for terrorism. As Orwell said, there are some things that only an intellectual can be stupid enough to believe.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.