If It’s Not Brokeback, Fix It

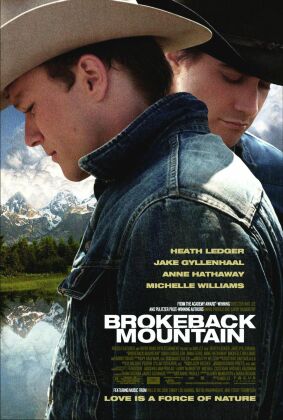

From The American Spectator“Smaller Films Sweep Oscar Nominations” headlined the Wall Street Journal. “Small films with potent themes. . .” agreed the New York Times. Small films, maybe, but big names. Three of the five nominees for best picture are about famous people or events. Three of the five nominees for best actor portrayed, or impersonated, an already well-known celebrity. Or look at them in another way. Four of the five best picture nominees have a more or less explicit political agenda. Guessing what sort of political agenda will, I imagine, not be difficult. One of the nominees for best foreign film takes as its heroes two Palestinian suicide bombers. The picture with the most nominations, Brokeback Mountain, celebrates both gay love and, with it, the “gay” political agenda. Not far behind it are Good Night and Good Luck taking yet another well-deserved whack at “McCarthyism” — doesn’t Hollywood ever get tired of knocking down its favorite hate figure after George W. Bush? — the why-can’t-we-all-just-get-along racial soap opera, Crash, and Munich, Steven Spielberg’s paean to the fine moral properties of Jewish guilt.

Other movies to receive multiple nominations include one, Syriana, attacking big oil companies — with a charge at the CIA and the American foreign policy establishment thrown in as makeweight — and another, The Constant Gardener, attacking big drug companies; one, Transamerica, has a hero — or heroine — who is a transsexual and another a hero who is a pimp trying to make it as a rapper; one, North Country is about a lady miner who breaks an all-male monopoly of mining jobs — how inspirational is that? — and another, Mrs Henderson Presents, celebrates the breakdown of British sexual prudery during the dark days of the Second World War. A History of Violence and Crash join Munich in warning us against the dangers of engaging in “violence” — even self-defensive violence — unless, of course, you are a fanatical Islamicist suicide bomber, in which case violence is understandable and excusable and you can expect to be treated quite sympathetically.

Could there be any connection here between these politically-themed movies and the decline in box office receipts during 2005? That Western Union sent its last telegram only a few days before the nominations were announced may have been what prompted the Academy to celebrate in such ostentatious fashion the final overthrow of Sam Goldwyn’s famous dictum that “Pictures are for entertainment; messages should be delivered by Western Union.” But that doesn’t mean that all these message-movies have since learned to become entertaining — or, which comes to the same thing, enjoyable to those who don’t share their strongly-held political opinions. The New York Times published a cutesy little editorial pretending to wonder what meaning the Academy should be regarded as attempting to convey by its choices.

The task of deciphering this year’s nominations is a little easier than in past years. The best picture nominees include mostly independent films with low budgets and serious subjects. This pattern could be merely the hangover from the “Lord of the Rings” years. It could be the academy’s response to the grievous condition our world is in. . . Or, it could simply be that these mostly very good films are really the best movies released in 2005.

This typically lumbering attempt at wit disguises the extent to which the Oscars have in fact become Hollywood’s method of congratulating itself for political rectitude on behalf of liberal and left-wing causes. And the greatest of these causes in Hollywood — greater even than self-righteous moralizing about that now familiar “cycle of violence” — is the one that has most to do with buttering Hollywood’s bread, namely the unwavering assault on the culture of “repression” and (as Hollywood supposes) its “patriarchal” roots.

The argument of Brokeback Mountain’s critics and apologists is roughly between two contending views of it. Is it about homosexual love or is it just about love? The movie’s makers and sponsors in their press campaign understandably but with an unconvincing positiveness make the case for mere love. Ang Lee, the director, has said that “This is a universal story. I just wanted to make a love story” — and that disingenuous self-characterization has been echoed in review after review by those who are grateful for an excuse not to classify it among downbeat gay problem dramas. A much more insightful review in the New York Review of Books by Daniel Mendelsohn, who loved the film, makes a strong case that that’s just where it should be classified. To him, it is a very specifically “gay tragedy” But in my opinion, both these views are mistaken. The film is neither about gay love nor about love tout court but yet another of Hollywood’s seemingly endless stream of exercises in vulgar Freudianism and romanticizations of the inhibition-less and unrepressed life.

Thus the main purpose of the juxtaposition of gay love and that wild, masculine outdoor life of ridin’ and herdin’ and fishin’ and shootin’ is not just to excite gays with images of butch cowboy love or even to make the case for an emotional continuum — and therefore the exciting possibility of a seamless transition — between male friendship and homosexuality, though it does make that case too. Rather, it is to show us unforgettable images of toxic masculinity. Its hero, played by Academy Award Best Actor nominee Heath Ledger, is literally rigid with repression. He can barely walk or open his mouth to speak, so stiff is he. Love there is, of course, and more of lust, but of more interest than either to Mr Lee, to his brace of screenwriters, Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana, and to Annie Proulx, on whose story the film is based, is the loving but terrified depiction of that most potent of contemporary bogeymen, the dreadful spectre of not being able to live a life of complete sexual fulfilment.

Most people don’t, of course, though most of those learn to rub along with what they’ve got. But making do in the face of life’s little disappointments is not something at all approved of by the enemies of repression. To them, as to the minds behind Brokeback Mountain, not having what you want is tantamount to a death sentence. At one point Mr Ledger’s character, Ennis Del Mar, says to his gay lover Jack, played by Academy Award Best Supporting Actor nominee Jake Gyllenhaal, “If you can’t fix it, Jack, you got to stand it.” Most of us, especially those of us raised by more or less stern papas to “take it like a man,” will approve the sentiment. Hollywood does not. In Hollywood’s dream world there’s never anything, at least anything sexual, that can’t be fixed. And the way you fix it is by doing what feels good. That’s why Brokeback Mountain is — like other gay-themed pictures such as Angels in America by Academy Award Best Screenwriter nominee (for Munich) Tony Kushner — a Bad Dad movie.

Ennis himself is a pretty bad dad to two daughters, but that’s only because all his models, and pretty much all society’s too in the era (1960s and 1970s) of the film’s setting, were even worse. His own dad died when he was a child, but not before showing him as a terrible warning another sort of broke back: the shattered body of a homosexual rancher murdered and mutilated by gay bashers. Jack, who goes in for bull-riding at the rodeo, has a dad who was also a rider but who is impossible to please, according to Jack. He “never taught me anything, never once came to see me ride.” Jack leaves home when still young to make his own way in the world. Both Jack’s old man, when we finally meet him in the person of Peter McRobbie, and his almost equally unattractive father-in-law (Graham Beckel) are presented to us as domestic tyrants, dominating and manipulating wives and children by means of intimidation. The message is clear enough for Western Union: traditional standards of masculinity produce only spirit-killing “repression” and the deep unhappiness that repression inevitably produces.

It’s a point of view, of course, though hardly an unfamiliar one in the movies of the last — oh, I don’t know, 30 years? The Academy could have made a much more daring choice by picking as a Best Picture nominee Cinderella Man,which only received nominations for editing and make-up — and a make-up to Paul Giamatti, overlooked in last year’s Sideways, with the chance of a Best Supporting Actor nod. But Cinderella Man had no Bad Dad to offer. Only a good dad, and one, moreover, who knew something — and taught something — about being a man and learning to stand what you couldn’t fix. Once upon a time — back, say, in the days of Brief Encounter (1945) — the movies were not averse to tales of heroic repression. Now, a movie like that would be simply unimaginable. Now we live in a world — at least a world of popular entertainment and the media — where goodness can only mean doing what you want. That, if the New York Times wants to know, is the message Hollywood was sending with its Oscar nominations.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.