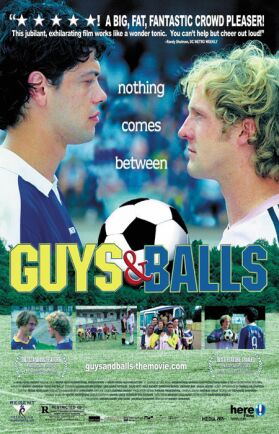

Guys and Balls (Männer wie wir)

Guys &Balls (Männer wie wir), directed by Sherry Horman and written by Benedikt Gollhardt, is based on the perennial gay fantasy of the latent homosexuality of those involved in such manly pursuits as soccer — or football as it is known to the rest of the world. Ecki (Maximilian Brückner) is the goalie for Boldrup F.C., a local German semi-pro team, and he has ambitions to play professionally. During a big game, in which victory would mean promotion for Boldrup and more money for its players, Ecki blows the save of a last-minute penalty kick and is mercilessly teased and insulted by his disappointed teammates, particularly the thuggish Udo (Carlo Ljubek). In dejection, Ecki finds himself rough-housing with one of the more sympathetic members of the team until, in a convenient entanglement of limbs, it seems natural for him to kiss him. Just at this moment Udo happens along and loudly announces: “Now I understand it! We’ve got a queer for a keeper!”

“I don’t understand it myself,” Ecki tells his stunned and disapproving father (Dietmar Bär). He has had a girlfriend, Cordula (Judith Hoersch), whom we have seen on the point of offering herself to him, but with Udo’s taunt he suddenly realizes that he is gay. If so, it must be said that Ecki’s progress in gay consciousness thereafter is rocket-like in its rapidity. When Udo has him kicked off the team, he challenges him and Boldrup to a match against a scratch side of gay footballers, to be assembled by him in four weeks’ time. Considering that he is inexperienced in sex of any kind and knows no one who is gay besides himself, this challenge suggests the monumental self-confidence of a practised seducer. And, sure enough, when he goes off to stay with his sister, Susanne (Lisa Potthoff), in Dortmund, he not only assembles his team but also meets his first boyfriend, Sven (David Rott).

At the same time, the film has to hold on tight to Ecki’s inexperience in order to milk it for comedy as he cruises the gay bars of Dortmund. At one point, after he only escapes at the last moment before losing his innocence to a terrifyingly large and leather-clad person who has put him in a swing, he even tells Susanne, “I’m not so sure I’m gay.” Of course, the doubt soon passes. Uncertainty as to sexual orientation properly belongs only to ostensibly heterosexual guys who haven’t yet realized that they are “really” gay. Thus the Turkish lad, Ercin (Billey Demirtas), whom with multicultural enthusiasm Ecki recruits from behind the counter at his family’s restaurant, assures the others that his hero, the English star David Beckham, is gay.

“But he has a wife and two kids,” objects one of them.

“Doesn’t matter. He’s gay as Tonto. He just doesn’t know it yet.”

By the way, Ercin is not the first to have given expression to this opinion, but in the context his remark hints at the hope if not the conviction that all the world is gay and just doesn’t know it yet. Thus when the two sides meet in the inevitable Big Game at the climax of the film, the war-chant of the Boldrup lads — “Bang ‘em, bang ‘em, cream the queers!” — is meant to suggest that even Udo and Co are so hostile because they are in denial about their own latent homosexuality. At the same time, and I think rather self-contradictorily, the film insists on the bright and uncrossable line between gay and straight that is necessary for the claim to protected minority status. There can be any number of those who think themselves straight but who are really gay, but never anybody who thinks himself gay but who is really straight.

When someone cites the dubious Kinseyite figure, to which some in the gay movement continue to cling, of the ten per cent rate of homosexuality’s occurence in the general population, we are encouraged to see Ecki’s exclusion and banishment by the other ten men on his original team as a synecdoche for the exclusion and oppression of gays by the dominant straight culture. There are, of course, various kinds of gayness, and the film’s running of the gamut of gay stereotypes from leather-clad bikers to the mincing and effeminate Ercin, is meant to imply a kind of diversity. But what all of them have in common is the ironclad certainty that they are defined by their sexuality.

Thus Rudolf (Christian Berkel), one of the leather guys, says to his eight-year-old son Jan (Marcel Nievelstein) whom apparently he hasn’t seen in two years: “It took me a very long time to find out who I am, and then I couldn’t stay with you anymore.” This seems to be intended literally, since Rudolf’s ex-wife and Jan’s mother (Sybille J. Schedwill) is a malevolent harpy who has somehow managed to obtain a court-order preventing him from seeing his son. How she could have done that in this day and age, and in progressive Germany, we forbear to inquire, but the idea of who I am as the excuse and license for every sort of self-indulgence is not quite excluded. For like Brokeback Mountain and other gay-themed movies of recent years, the real point of Guys and Balls is to stress that the indulgence of the sexual appetite without constraint is not so much a right as a sacred duty — indeed, the sacred duty, since it nullifies even the holy bond of marriage. The movie’s apparent freedom and lack of inhibition give rise to a lot of fun, but underneath it all there is an uncompromising agenda.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.