Forever Young

From The American Spectator“I was waiting for someone to come along, some young singer 18 to 22 years old, to write these songs” says Neil Young of “Living With War,” his latest album of “protest” songs — one of which is titled, “Let’s impeach the president.”

Let’s impeach the president for lying

And misleading our country into war

Abusing all the powers that we gave him

And shipping all our money out the door.

“I waited a long time,” continued Mr Young, a Canadian by birth. “Then I decided that maybe the generation that has to do this is still the Sixties generation. We’re still here.” Boy are they ever! Or, as I should say, Boy are we ever. For I was, I now blush to admit it, one of those protesters back in the 1960s who thought that “All you need is love” and that we ought to “Give peace a chance” so we might “Make love, not war.” But then that’s sort of the point isn’t it? Mr Young, who turned 60 on his last birthday, isn’t blushing for his youthful naïveté. On the contrary! He’s still — in terms of politics, anyway — every bit the lusty, protesting vigintinarian he was in the Vietnam era. Or, to put it another way, he hasn’t learned a thing in 40 years.

Alas, of how many of my coevals can the same be said! The very title of Mr Young’s album proclaims his innocence, suggesting as it does that there is some alternative to “Living With War” — besides, that is, dying with war. The war part is as much a constant of human history as wearing clothes or using tools. In fact, the first tools were probably weapons. Yet Neil Young continues to warble of how, in that special, Neil Young world that he so proudly offers us in place of reality, we “won’t need no stinkin’ war.” As Hemingway used to say, Wouldn’t it be pretty to think so? The surprising thing is not so much that a man of mature years should continue to cling to the political outlook of a child but that he should be proclaiming the fact to the world without the faintest sign of shame or embarrassment.

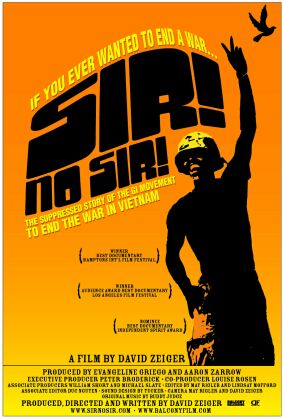

There must have been something about Vietnam, either the experience of the war or of the protests against it, which did this to people, delaying the onset of political puberty or even stopping it altogether. The alternative for others was to side with the enemy, which seems to have been the course favored both by David Zeiger, director of the documentary Sir! No Sir! and by his subjects, who were the military officers and enlisted men during the Vietnam era who joined antiwar protests — and sometimes actively sought to sabotage the American war effort — while still in uniform. To listen to Mr Zeiger, you’d think that American soldiers in Vietnam were of only two kinds: war criminals and those who, like his subjects, protested against their crimes and sought to expose them to public view. Not the slightest effort is made to understand why America was in Vietnam in the first place, and no credit is given to the Johnson or Nixon administrations even for good intentions. They are as perfectly bad as the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong enemies are perfectly good.

You could at least see the point of such crude propaganda at the time. These guys had a war to stop, after all, and eventually they did stop it — thus effecting the immiseration or death of millions of Vietnamese and Cambodians and crippling America’s ability to conduct foreign or military policies around the world for a generation. But now, more than 30 years later, you’d think it would be time to step back from the caricature version of the war and explain in grown-up terms what was going on during the eventful couple of decades that it took for American policies in and about Vietnam to produce the catastrophe they did. You’d think so, but you’d be wrong. And why? Just look at the tag-line for Sir! No Sir! It reads: “If you’ve ever wanted to end a war. . .” In other words, like Neil Young, they’ve got another war to stop, so out come the love beads and the tie-dyes and the bell-bottoms along with all the old clichés about America’s iniquitous plan to oppress the gentle, freedom-loving peoples of the Third World.

But wait a minute. Why the artful analogy? Why make a movie about Iraq set in Vietnam? Could it have anything to do with the implausibility of casting murdering Ba’athist thugs and al-Qaeda terrorists in the role of the gentle, freedom-loving peoples of the Third World? Your simple, pajama-clad Vietnamese peasant is always going to make a better victim of Amerika and its fascist leaders than your Iraqi suicide bomber, seeking to kill his co-religionists and fellow Iraqis as well as the troops of the Great Satan, who have come to try to keep order and establish democracy among them.

|

It’s now hard to believe that, as recently as True Lies (1994), the American security services could be portrayed as the good guys and Arab terrorists as the bad guys in a mainstream Hollywood movie. Now of course the villains are invariably neo-Nazis or oil-company executives. Or the American security services. A fondness for the idea of the enemy within, concealed beneath the cloak of patriotism and honor, is another of the legacies of the Vietnam era that is making a comeback in Tinseltown — as, for example, in the two movies (a third is due out next year) in the series featuring Robert Ludlum’s renegade CIA agent, Jason Bourne (Matt Damon). The director of the second and third of these, Paul Greengrass, has taken a little break from exposing corruption in the fictional U.S. government in order to expose incompetence in the real U.S. government in United 93. The essence of this movie lies in the contrast, established by constant cross-cutting, between the cluelessness of officialdom on the ground and the bravery of the passengers on the flight that crashed in Pennsylvania on 9/11 who fight back after realizing that “We have to do something. Nobody’s going to help us.”

Unfortunately, this is a case in which criticism of America’s civil and military authorities appears to be well-deserved. They really were pretty clueless on that awful day, and the passengers really did have to fight back because there was no help for them from outside. Yet isn’t there also something just a bit off, just a bit screwy, about making this contrast the focus of the film? After all, the events of 9/11 are of a historical importance comparable to that of Pearl Harbor sixty years before. The enemy which identified itself on that day knew that it was challenging America in a way that could not be ignored and that would produce a long war determinative of American foreign and military policy for years, if not decades. To concentrate on the initial shock of the opening blow of that war, and its consequences in the air and on the ground, is not illegitimate, but it’s a bit like making a World War II movie about Admiral Husband Kimmel, who carried the can for Pearl Harbor, rather than Nimitz or MacArthur. It’s kind of beside the point.

For the point is, as Hollywood during that war would very well have understood, the heroism of the passengers and the wickedness of the treacherous enemies determined to kill them — and as many other Americans as they could. How hard can that be to figure out? But that moral template looks crude and inadequate in the post-Vietnam media culture geared up only to find wickedness in America’s civil and military authorities, or American business, and never in America’s declared enemies. That’s why United 93 downplays both the heroism and the wickedness. The memorable catch-phrase associated with Todd Beamer, “Let’s roll,” is reduced to a querulous complaint rather than a rallying-cry, and none of the four known heroes is identified by name. Mr Greengrass’s otherwise energetic camera goes slack and lazy once the counter-attack begins, surveying in a detached sort of way the sea of heaving bodies without making much in the way of an effort to pick out and hold up for our inspection the heroic acts which must have been performed that day.

Meanwhile, the hijackers are always identified with their human and emotional reactions to what is occurring — their nervousness and fear and, on at least one occasion, their attachment to loved ones on the ground, just like the passengers — and not with the Death to America rhetoric which put them on board Flight 93 in the first place. Naturally, the movie has been congratulated by many critics for the taste and sophistication of its refusal to commit the vulgar error of providing a strongly marked moral framework in which to understand what is going on. Yet it seems to me that there is also a kind of naïveté in thus pretending that the emotional always trumps the moral, the human identity the patriotic, the victim the hero. That was a belief that inspired idealists like Neil Young and me back in the glory days of the ‘60s but, looking back, some of us at least would say that it didn’t work out all that well, either for America or for the world.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.