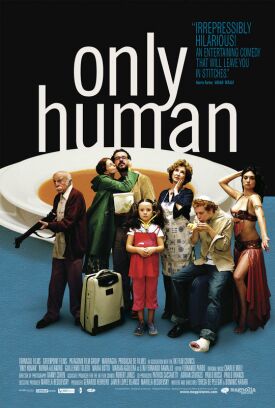

Only Human (Seres Queridos)

The Spanish title of Only Human by Dominic Harari and Teresa Pelegri is Seres queridos, or “loved ones” and suggests one of those happy-clappy, boosterish Euro-junk films, like Cédric Klapisch’s Auberge Espanole, in which everybody is part of one big happy European family living in a tolerantly multicultural spirit stronger than any differences between them. This impression would not be altogether mistaken either, though Only Human also has a bit of an edge to it and is a lot funnier than we might expect of such a movie. Leni Dali (Marián Aguilera) and her fiancé, Rafi Abdallah (Guillermo Toledo), are a multicultural revolution in themselves. She is a Spanish Jew, the grand-daughter of a man who fought in the Israeli war of independence in 1948, and he is Palestinian, a teacher of Arabic literature living in Spain.

The film begins with Leni’s bringing a nervous Rafi to meet her family in their high-rise apartment, and lots of comic events ensue. Leni’s brother, David (Fernando Ramallo), keeps a wounded duckling in the bidet and, having re-discovered his Jewish roots, has taken it upon himself to police his otherwise non-observant family to make sure they keep kosher and observe the Sabbath. He calls himself by the family’s original last name, Dalinski — perhaps, attempting to wipe out the inevitable hint of the surreal. David has the funniest line of the movie when big sister Tania (María Botto) makes some dismissive remark about his religious obsession and he replies with the certainty and the sententiousness of youth that “Atheism is a luxury of the bourgeoisie.”

Tania, still living at home and scraping a few extra Euros by belly-dancing in the evenings, is the single mother of Paula (Alba Molinero). Her mother, Gloria (Norma Aleandro) is in despair about her promiscuity. When Leni defends Tania by saying that “she needs fun,” their mother replies: “So do I, but being a nymphomaniac and a mother are not compatible.” Not too surprisingly, mom isn’t getting much fun out of dad, who is not present when Leni and Rafi arrive. He is working late because he has recently been demoted at the office. We gather that Leni is the golden girl, the hope of the family, while Tania is the black sheep. Everybody immediately welcomes Rafi, assuming that he is Jewish too, as he comes from Jerusalem. Leni’s grandfather, Dudu (Max Berliner), who is blind, shows him his old British-made Lee-Enfield rifle from 1948 and demonstrates, now without any need for a blindfold, that he can still take it apart and put it together with his eyes closed. When, unknowingly, he points it at Rafi, Gloria takes the weapon from him and puts it up on a high shelf, saying: “Tomorrow this goes to Oxfam.”

She is trying to prepare the family meal while doing a hundred other things, and Rafi offers to help by heating up the frozen soup. But as he tries to extract it from its Tupperware container, it slips from his grasp and goes flying out the open window. He looks out to see that the block of frozen soup, falling from several stories up, has hit a man on the head, knocking him out and perhaps killing him. When he goes downstairs to do something about this casualty, Leni advises him, without looking at the prostrate man, to call an ambulance anonymously and act as if nothing had happened. He thinks this wrong, but yields to her as he usually does. “She always gets what she wants,” he later confides to Tania: “not because I give in, but because she convinces me.

But when they come back upstairs, Paula’s drawings of her grandfather persuade Rafi that he has killed Leni’s father. By this time, the man, or his body, is gone, and it becomes a matter of some urgency for him and Leni to find him. At the same time, Tania has revealed her suspicion that her father’s late nights at the office are meant to disguise the fact that he is having an affair. So Leni and Rafi and Gloria and Tania all rush off to the office where he is supposed to be, all of them hoping for different reasons to find him there. David is left behind with Paula and discovers the damning evidence in Rafi’s suitcase that he is an Arab and not a Jew. At this point, Rafi has already confessed as much to Gloria, who cannot repress her overwhelming sense of the disaster to the family that this unwelcome information represents. Fortunately, she has no time to dwell on this during all the fast-paced to-ing and fro-ing in search of her husband.

My favorite line from the movie, more profound than funny, is Gloria’s reply to Leni’s heartfelt plea that the national and religious differences between her and Rafi don’t matter because “We love each other.”

“So did Romeo and Juliet,” says mom.

“That was in the middle ages,” replies an exasperated Leni.

“This is the middle ages,” says her mother.

If only the movie could have explored that idea a little further! But I suppose that would have been too downbeat and, anyway, the movie doesn’t believe it. There is just a moment when everyone, the usually optimistic Leni included, seems ready to despair of a life that has become so hard and that seems to offer so little hope. But nothing is as bad as it seems and love carries the day for the family, if not for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We are left with just the suggestion that there must also be hope even for that most intractable of international situations. But it would be easier to believe that if we could imagine Arabs laughing at this movie along with the Jews. I don’t see it myself.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.