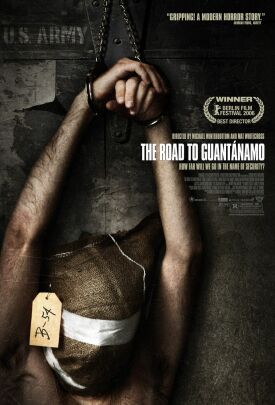

Road to Guantanamo, The

Whatever may be the merits of Michael Winterbottom’s Road to Guantánamo, and they are several, it is undoubtedly an effort to hinder and obstruct the Bush administration’s war on terrorism. We have to understand this at the outset because that effort’s success or lack of it will depend on the film’s effectiveness at disguising the fact — and it seems very effective to me. What it pretends to be about is the sad story of four young men of Pakistani descent from Tipton, near Birmingham, England. It is October of 2001, and Ruhel (Farhad Harun), Shafiq (Riz Ahmed), Asif (Arfan Usman) and Monir (Waqar Siddiqui) travel together from England to Pakistan because Asif’s family has arranged a marriage for him there, a common occurrence in the Anglo-Pakistani community. On a whim, the four decide to take a side-trip to Afghanistan just in time to be caught up in the civil war between the Taliban and the Northern Alliance, aided by elements of the U.S. armed forces. Monir disappears, never to be heard from again. Ruhel, Shafiq and Asif are identified as Taliban fighters and interned at Camp X-ray, Guantánamo.

There, they suffer hardships and harsh treatment amounting at times to what some would describe as torture. This includes isolation cells, loud noises and being in “stress positions”; there are also stray punches and slaps and, in one case, where one of the prisoners is supposed to be insane, a severe beating. At another point, an American guard is seen desecrating a Koran. Of course, we have only the men’s own testimony that any of these things actually happened. But the film is straightforwardly a conduit for that testimony and makes no attempt to evaluate it or assess its reliability. It shows them bravely and defiantly enduring it all, always insisting on their innocence of any connections with the Taliban or terrorism until, slightly more than two years later, they are released for lack of any evidence that they were ever terrorist sympathizers.

Mr Winterbottom (Wonderland, In this World, 9 Songs) is a talented film-maker and, co-directing here with Mat Whitecross, masks the propaganda beneath the compelling human story told by cross-cutting interviews with the three survivors, now inevitably “the Tipton three,” and a running dramatization of their experiences in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Cuba. Every now and then, too, we cut away to glimpses of the larger war on terror in vignettes — such as a speech by President Bush on Guantánamo in which he says that “one thing we do know: these are bad people” — rendered deeply ironic by their context. In fact, Mr Bush’s announcement must have included some such unspoken qualification as “so far as we know” or “the overwhelming majority” and an understanding that rounding up terrorist suspects on the basis of the limited knowledge we are bound to have of organized terror operations is pretty much bound to sweep in some innocent along with the guilty.

That’s if they are innocent. I must say that the three men’s story sounds a bit thin to me. They were in Pakistan for a wedding and just decided one day to take a trip up to Afghanistan where they were “basically just chilling out”? They could hardly not have known that American warplanes were bombing the hell out of the place at the time, yet they just wanted to play tourist? Then, when they got scared and wanted to return to Pakistan, a sinister and unknown bus driver took them in the opposite direction, toward the front line. It all sounds just the tiniest bit fishy to me. But say they were innocent. The fact doesn’t tell us anything about the hundreds of others caught in the same dragnet, let alone about whether or not the acts of terrorism that must have been prevented by their incarceration made it worthwhile to risk imprisoning the odd innocent man.

The film ignores all such questions because its purpose is to make as much as it can of the three innocents in order to suggest that the other internees are as likely to be innocent as they are. In other words, Mr Winterbottom wants to say not just that it’s unfortunate that the men were imprisoned at Guantánamo, or even that it was wrong for America, not knowing of their innocence, to imprison them. He means that it is wrong for America to imprison anyone, guilty or innocent, at Guantánamo — which just happens to be the view of the increasingly vocal anti-war and anti-Bush left. Those who recognize that we are at war, and that there are dedicated terrorists looking for opportunities to kill innocent Americans, are likely to think differently. If we have good reasons for suspecting certain foreigners of plotting murder and mayhem against us, on what moral or prudential grounds are we told that we must do nothing but wait until they have killed more Americans — by which time they will presumably have blown themselves up anyway?

At the critics’ screening I attended in Washington, there were “peace” activists openly recruiting demonstrators against the Guantánamo prisons. Their presence only confirmed my impression that The Road to Guantánamo never bothered to make any pretense of being anything but propaganda. Like Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will — or Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth or Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 — it depends on the assumption that anyone who watches it will already be in sympathy with its aims. And the demographics of movie-going suggest that the assumption is pretty much correct. No need, then, to apologize their blatant partisanship or make any attempt to be judicious or even-handed with their material. The Road to Guantánamo is highly watchable, as we would expect from Mr Winterbottom, and an absorbing tale if it were fictional. As it is, however, we cannot but be aware that the real-life subjects have an agenda, as does the film itself, which subtly alters our response to a human story that would otherwise be enthralling.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.