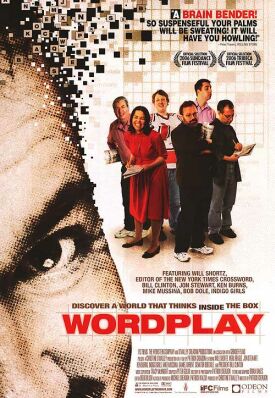

Wordplay

Patrick Creadon’s Wordplay is a delight for those who, like myself, enjoy doing crossword puzzles. It’s also depressing. This is because so much of it takes place at the annual Crossword Tournament in Stamford, Connecticut, and we get to watch as people who are impossibly good at solving the New York Times’s most difficult puzzles show us what duffers we are by comparison. Starting out as a documentary about the Times crossword, its current editor, Will Shortz and some prominent people who are addicted to it, the film soon loses focus on anything but the tournament, in its account of which it offers us a classic sports movie scenario. We meet the various contenders for the title in their homes, learn a little bit about them, and then follow them to the climactic confrontation in Stamford.

Everyone will have a favorite to root for, and the championship round — in which the three finalists stand on a stage, each with a felt-tip marker and a blow-up of the same puzzle on an easel, and the first to finish it without mistakes wins — is a real nail-biter. The three are Al Saunders, a middle aged family man who works for Hewlett-Packard in Colorado, Trip Payne, a young gay man from Ft. Lauderdale, and Tyler Hinman, still an undergraduate at Rensselaer Polytechnic who, if he wins, will be the youngest champion ever. In addition, we meet several past champions — who tend to be musicians or mathematicians — lesser competitors and others who come to the tournament every year because they feel part of the competitive crossword-solvers’ “family.” One woman says her husband died at the tournament in 1981, and she keeps coming back because it makes her feel closer to him.

The movie’s account of the tournament continues to be interspersed with information about the Times’s crossword and interviews with celebrity crossword solvers, including Bill Clinton, Jon Stewart, Ken Burns (all of them left-handers, we notice), Mike Mussina and the Indigo Girls, as well as compilers of the puzzles like Merl Reagle, whose composition of one for Mr Shortz as we watch is as impressive in its way as the feats of the lightning fast solvers.You will learn some of the rules of puzzle composition that you may not know, such as that a sixth of the squares must be black and that the pattern of black and white squares must be symmetrical. There is also the “Sunday morning breakfast test” which rules out any answers that refer to bodily functions.

I would have liked to see the documentary part of the film cast its net a little wider — for instance to show us the equally amazing people who solve the cryptic, British-style crosswords that I prefer, where “flower” (probably) calls for the name of a river (a flow-er) and “shaken” (almost certainly) signifies that the word before or after it is an anagram. These require rather different skills from the American puzzles which are more dependent on general-knowledge and make the words play less puzzlingly and less frequently. But for anyone who has ever spent any time being frustrated by the New York Times crossword, which is most of us, this film will come as a treat.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.