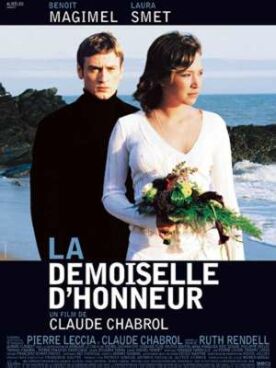

Demoiselle d’Honneur, La (The Bridesmaid)

Claude Chabrol’s The Bridesmaid (La Demoiselle d’Honneur), which came out in 2004 but is only now finding a release in the US, is a classic Chabrol-type study of the point where passion and madness intersect with ordinary life. Passion is represented by Senta (Laura Smet), who has changed her name from Stéphanie to adopt that of the heroine of Wagner’s Flying Dutchman — the girl whose faithfulness unto death redeems the cursed hero as well as herself. Ordinary life is represented by Philippe (Benoît Magimel), who meets her when she serves as a bridesmaid at his sister’s wedding and falls hopelessly, fatally in love, as she does with him.

Philippe is firmly anchored in an everyday reality by his job, working for a builder called Nadeau (Pierre-François Dumeniaud), which involves meeting and pacifying cranky customers, and by his mother, Christine (Aurore Clément) and younger sister, Patricia (Anna Mihalcea), with whom he still lives. As a dutiful son, he naturally also assumes a quasi-paternal role towards Patricia whose wildness and fast living are constantly getting her into trouble. “Virtue sucks,” she says. “I wasn’t born to have a bad time.” This is not Philippe’s view. His own father deserted the family long since, and he had to grow up early.

Now, to add to his worries, the new man in his mother’s life, Gérard Courtois (Bernard Le Coq), appears to be trifling with her affections. Christine herself, accustomed to being disappointed by men, accepts Gérard’s abandonment philosophically and redoubles her affection for her son, whom she says is “as handsome as an angel.” So far we have familiar and unremarkable slice of bourgeois life in provincial France today, but the mysterious Senta is clearly something much more extraordinary. She lives alone in the basement of a big old house she shares with her mother, who lives on the upper floors and has little if anything to do with her daughter, preferring to spend all her time practising the tango with a boyfriend.

Senta decides at the very outset of her relationship with Philippe that “You’re the one I was waiting for. You’re my destiny, and I am yours.” Instead of running away from such a disturbingly precipitate claim upon him, the formerly earnest young striver and dutiful son embraces it and adopts Senta’s view of the relationship as fated. But she’s not going to make it easy for him. She has decided, she says, that there are four things they must do to prove their love for each other: plant a tree, write a poem, sleep with someone of their own sex and kill someone. Perhaps fortunately we never get around to the first three items on the agenda, but the fourth proves to be, not too surprisingly, a bit of a sticking point for poor old Philippe. At first he has the strength flatly to refuse to kill anyone, and she throws him out of her home. But when Senta re-appears at Philippe’s mother’s door to reclaim the bridesmaid’s dress that she couldn’t wait to get out of on visiting Philippe there, their affair resumes.

Philippe sees an item about a tramp who has been murdered and, thinking it to be the tramp (Michel Duchaussoy) who to her annoyance has been camping in the yard of Senta’s house, claims to have killed him. Senta is overjoyed at this proof, as she sees it, of his love and proceeds to do the same for Philippe by killing Gérard Courtois. Philippe is worried when she tells him about her murder — with a Venetian glass dagger to the heart while her victim was taking a speck of dirt out of her eye. But after driving out to Gérard’s new house and finding him alive and well, he assumes that she has made it all up just as he did. This makes him happy. The match may be fated but it won’t, after all, be fatal.

Little does he know! The film in effect poses the question: is it better to be in love with a liar and a fantasist who can give you a satisfying but boring bourgeois existence or with someone much more exciting who is completely truthful but who may do horrible things? When Philippe thinks Senta has merely fantasized about the killing of Gérard, he is immensely relieved and so in love that he’s happy to play what he now imagines to be her little fantasy game. Life can go on in the ordinary way. But then comes the moment of shock and surprise when fantasy unexpectedly seems to morph into reality and he is forced to make a decision. If she’s not a fantasist, does he repudiate her for not being one or love her all the more for being true to her own bizarre vision of their destined love?

It’s not a question whose answer is self-evident to him, and we can just about see why. The trick of the film, for which Chabrol deserves a lot of credit, is that its heroine’s obvious mental derangement is never allowed to descend into mere pathography. Senta is a disturbing figure in all kinds of ways, but she raises an important question about love and destiny that is designed to appeal to the French romantic imagination as shaped by its post-war and highly politicized romance with madness and criminality. That’s all very well and good, of course, if you’re a French romantic, and just about worth sitting through if you’re a romantic of any description. But Americans trained in Hollywood’s merely sentimental version romanticism are not likely to find much to like about this film.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.