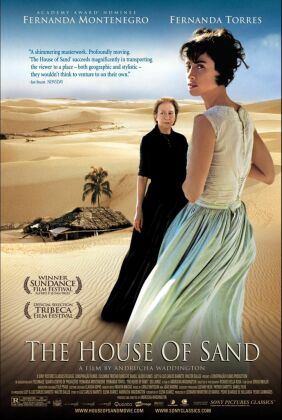

House of Sand (Casa de Areia)

House of Sand (Casa de Areia), by the Brazilian director Andrucha Waddington from a screenplay by Elena Soárez, is a woman’s picture, set in a masculine — indeed, a heroic — landscape which dwarfs the men and animals making their painful way across it in the opening scenes. What we see are the wild and desolate sand flats and dunes of the Maranhao state in Brazil’s equatorial North, on the pounding Atlantic. It is 1910 and the little band arriving from somewhere far in the south must have traveled by foot and donkey more than 2000 miles to get there. Obviously, they haven’t come all that way for nothing. But it’s different for the women. The restless, ambitious, exploring men may be pursuing a grand and noble dream — we know little or nothing about what it might be — but the women have come because they had to. The men endure hardship for the sake of winning or achieving something; the women simply endure.

The leader of the party, an old man called Vasco de Sá (Ruy Guerra), claims to have “bought” his young wife, Áurea (Fernanda Torres), by paying her debts. This is what he imagines has given him the right to bring her and her mother, Donna Maria (Fernanda Montenegro), along with some hired men to this god-forsaken place, inhabited only by runaway slaves who, though slavery has been abolished in Brazil, don’t trust to the law for their freedom. At least they could run away. Áurea and her mother, the de facto slaves of Vasco, are desperate to escape, but Áurea’s pregnancy makes this impossible on their own. She pleads with Vasco to be allowed to return whither they have come, but he turns a deaf ear. “There’s no going back, Áurea. No going back.” His words prove prophetic.

With materials supplied by the slaves, especially Massu (Seu Jorge), Vasco builds a ramshackle house on the sand. Áurea refuses to enter it, and Vasco drags and pushes her inside. When his hired men run off, Vasco swears that he doesn’t need anybody, but he is killed in the collapse of part of the house he has built on the shifting sands — a motif to be repeated more than once — and the women are left alone.

Massu warns them: “Your house will sink.”

“We’re not staying here,” Áurea insists.

“Neither is the sand,” says Massu. “It sweeps everything away.”

But they are staying, in spite of Áurea’s hatred for the place, and the film uses the impermanence of the landscape, as of masculine striving, to contrast with the iconic permanence of womankind. At first they still expect to leave one day. When Áurea’s daughter Maria (Camilla Facundes) is old enough to make the journey, Donna Maria now says she wants to stay. “I am not going anywhere,” she tells Áurea after they have lived alone on the desolate coast for nearly 10 years. “I don’t miss it anymore,” she says of the city that Áurea so longs for. “I like it here; I have no man telling me what to do.”

The paradox of their having come to this place because of some man telling them what to do and then staying because of the relative freedom it affords them lies at the heart of the film, which is well made and visually impressive. Its chief virtue lies in the performances of the real-life mother and daughter, Miss Montenegro (Central Station) and Miss Torres who are also the real-life mother-in-law and wife of Mr Waddington. He has sought to create a sense of epic sweep by making the time-span of the film cover three generations and 60 years. Half way through, Miss Montenegro takes the part of the now aged Áurea and Miss Torres that of her daughter, Maria. It’s a remarkable transformation, as there is constant tension between the mothers and daughters, who all have distinctive personalities, but it is also a way of suggesting continuity and an almost geological sense of feminine permanence.

The passage of time is marked by events in the sky. An eclipse in 1919 brings scientists to the northeast coast of Brazil to prove Einstein’s theory and Áurea misses a last chance to get away. Then a flight of World War II -era aircraft tells us that we have arrived at 1942. Áurea’s daughter, Maria, now grown, escapes to the city, leaving her mother behind. Finally, the middle-aged Maria returns in 1969 to find the now aged Áurea still living between the sand and the sea and tells her that a man has landed on the moon.

“What did he find on the moon?”

“Nothing,” says Maria. “Nothing. I heard he just found sand.”

Not a lot happens in this movie. Or, rather, one is constantly aware of all that is happening off-stage while the unchanging sand and sea and sky where the women live make up, with them, a rebuke to the ambitions and pretensions of men. When Áurea meets Luiz (Enrique Díaz), the military escort of the scientists in 1919, he tells her as if expecting her to be excited that the war is over.

“I didn’t know it had started,” she says to him.

“It lasted for four years,” he says.

“And I have been here for ten. I think.”

Einsteinian relativity has nothing on these two contrasting views of time. Or rather of time and timelessness. The hint seems to be that men are concerned with history and the historic while women inhabit a kind of timeless and eternal present — even if it is profoundly against their will. It’s a compelling vision, though not one that leaves much room for love or wisdom or goodness or sacrifice. Presumably in the vast sidereal distances apparent here under what the scientists regard as “the best sky in the world” such things are of no more moment than human achievement.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.