We Don’t Need Another Superhero

From The Wall Street JournalDavid Gemmell, the British fantasy novelist and the author of Legend who died last week, once said that he had been inspired to write fantasy by the debunking of such historical heroes as Wyatt Earp, Wild Bill Hickok, George Armstrong Custer and Davy Crockett. “Societies need heroes,” he was quoted as saying. “So we travel to places where revisionists cannot dismantle the great.” But perhaps it is worth considering whether, as a society, we are paying a price for abandoning to the revisionists the rich heroic material supplied by reality.

It is surely no accident (as the Marxists say) that the fashion for debunking real-life heroes has coincided with the rise of fantasy heroes. Superman, still the most popular of the latter, made his first appearance in DC’s Action Comics in 1938 when post-World War I disillusionment with ideas of honor and heroism was at its peak. Not long afterward came Batman, Captain America and others.

Such fantasy figures enjoyed a huge popularity once America entered World War II. “The desire for some big, bright escape that had something to do with fighting off big, bad scary things was a big part of that,” says Gerard Jones, the author of Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book (2004). But it also tended to isolate and quarantine heroism in fantasy- land.

Even real heroes eschewed the name. “I’m just a guy doing a job,” said William Bendix in the war movie Guadalcanal Diary (1943), and this was a common way for fighting men to talk about what they were doing. Talk of honor, patriotism or noble sacrifice was frowned on by the comic- book-reading soldiers at the front.

Superheroes enjoyed another growth spurt in the Vietnam era, when a whole raft of new ones, including Spider-Man and the Incredible Hulk, were introduced by the two major players in the comic book world, DC and Marvel. At the time, Hollywood was still portraying fighting men that were real, if not always realistic. But with the post-Vietnam reaction against the military and its culture, the U.S. armed forces came to be routinely depicted as institutionally vicious and corrupt and individual soldiers as pathetic victims. There was no shred of heroism in the spate of Vietnam movies that began with Coming Home and The Deer Hunter (1978) or Apocalypse Now (1979).

Instead, the movie business joined in the cultural migration to fantasy with the first Superman movie (1978) and the original Star Wars trilogy — in which heroism existed but only in “a galaxy far, far away.” In First Blood (1982), even patriotism abandoned military institutions in favor of Sylvester Stallone’s John Rambo, who was a solitary superhero in all but name, taking on whole armies singlehandedly.

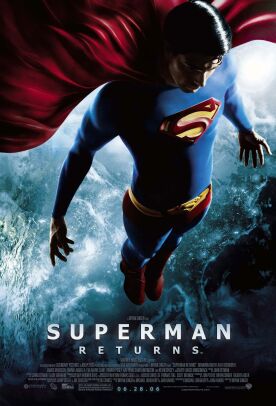

Since 9/11 the trickle of superhero movies has become a flood. There have been two Spider-Man and three X-Men movies (the first of which came out in 2000), as well as The Fantastic Four and The Hulk. They have joined a revival of the Batman and Superman franchises in last summer’s Batman Begins and this summer’s Superman Returns. Plans for sequels to the Hulk, X-men and Spider-Man movies are well advanced, and Captain America, The Phantom and Ghost Rider are also waiting in the wings.

The latest in superhero fashion is for irony, in the manner of the animated feature The Incredibles (2004) — who seem to have gotten their name from the epithet discarded by the Hulk a year earlier in a bid to be taken more seriously. After all, “incredible” can be pretty much taken for granted of all superheroes — unless, like the ironic cartoon ones, you want to make a point about their unbelievability.

In a similarly ironic vein, last year, we had Sky High, about a high school for budding superheroes. The arrival of their superpowers is analogous to if not precisely coincidental with that of puberty. Today there opens Zoom, which has basically the same idea. It follows hard on the heels of My Super Ex-Girlfriend, which is about the perils of breaking up with a girl who has superpowers.

It’s all a lot of fun, I suppose, but the more we indulge our appetite for the cultural junk food of the superheroic, the harder it becomes to digest the real thing. This is especially true for children, for whom this diet has been primarily designed. The pre-eminent childhood hero now is Harry Potter — to all intents and purposes another superhero. Kids have come to crave the sugar-buzz of superheroism to the point where, if they encounter ordinary heroism (if that’s not an oxymoron) in old books, it must seem bland and unexciting.

Can it be entirely coincidental that adults, too, have had their appetite for the heroic spoiled? Both of this year’s big 9/11 movies, for instance — Paul Greengrass’s “United 93” and Oliver Stone’s “World Trade Center” — have played down the real and undoubted heroism of some of their characters in order to emphasize the passive suffering of others.

On the plane that crashed in Pennsylvania, we know the names — Todd Beamer, Jeremy Glick, Thomas Burnett and Mark Bingham — of at least four of the men who led the passengers’ revolt against the hijackers, but Mr. Greengrass doesn’t mention them. Nor does he show them as being especially distinguished for their heroism.

This reticence, we know, was in deference to the wishes of the victims’ families, who co-operated with the film-makers on the understanding that, as the coordinator of Pennsylvania’s Sept. 11 victim-assistance program told the Washington Post in 2002, “we feel we have forty heroes, and not just four.” Why? Because all 40 suffered and died.

Real heroism, for us, is scarcely conceivable apart from victimhood. That’s why, in Mr. Stone’s film too, almost all the attention is on the two Port Authority policemen, John McLoughlin (Nicolas Cage) and Will Jimeno (Michael Peña), not their rescuers. McLoughlin and Jimeno spend most of the movie pinned helplessly beneath the rubble of the World Trade Center, while their families are waiting, equally helplessly, for news of them.

We may begin to suspect that American movie audiences scarcely know what the old-fashioned hero even looks like anymore, the sort who dares greatly and succeeds by mastering his enemies. On the rare occasions when we have seen one, as in last year’s boxing movie Cinderella Man, he has been a box-office disappointment.

Old-time heroes like Wyatt Earp or Davy Crockett may not have been all that we would now wish them to be, but they did have one big thing going for them that the superheroes don’t. Their undoubted bravery, resolution and fortitude in the midst of real dangers made them examples for us to emulate, not just fantasy figures to admire.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.