All the King’s Men

“Attitude” perfectly sums up the highest aspiration of much of today’s popular culture. It is to us what “respectability” was to the Victorians: the tribute we pay to the supreme importance of keeping up appearances. Indeed, attitude glories in appearance even more than respectability does.You could lose respectability, but attitude is forever. The respectable art of the Victorian era has mostly and mostly deservedly been forgotten, and I predict that the same fate awaits the “attitude” art — much of it in cinematic form — of our own time. The latest example of such art is Steven Zaillian’s adaptation of Robert Penn Warren’s novel, All the King’s Men, which enjoyed a certain reputation at one point as a fictionalization of the career of Governor Huey Long of Louisiana and was made into an Academy Award winning film with Broderick Crawford in 1949.

It has to be said that the novel itself, published in 1946, was to some extent an early example of attitude art, but Penn Warren effectively disguised the fact by swaddling his rather feeble mise-en-scène — the novel was essentially little more than one of a raft of self-consciously “disillusioned” post-war coming-of-age stories — in fine writing, masses of authentic-sounding period detail and hints of political seriousness. Of that camouflage, only the period detail survives in Mr. Zaillian’s movie. And, to give it its due, that’s not nothing. The washed out, faux black-and-white look of it — seemingly, 90 per cent of this portrait of sun-baked Louisiana is in night scenes — is gorgeous. Hollywood’s devotion to attitude does at least produce great visuals. But the hollowness — indeed, the vacuity — behind the appearance is all too cruelly exposed, especially in the film’s politics. Where Penn Warren had made the demagoguery of his Huey Long-like hero, Willie Stark, the back-drop to his tragic personal story, the new movie reverses the relationship, making the personal story into an incidental soap opera and moving the demagoguery to center stage.

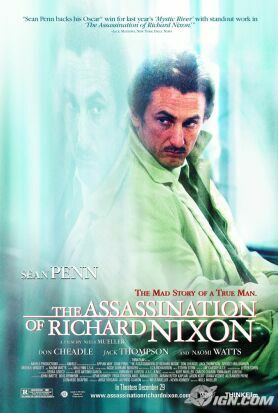

It doesn’t work, and a moment’s thought will tell us why. Willie is the governor of Louisiana: not a dictator, not a tyrant, not even a very important figure on the national scene. His future as a totalitarian and therefore a scare-figure is nil, and is seen to be nil. He’s a small-timer to the very marrow, which is what gave him his tragic stature in Penn Warren’s eyes. Yet Mr Zaillian gives us over and over again would-be scary shots of his Willie, Sean Penn, in the full-flood of a Hitlerian harangue to rapt crowds of poor Louisianans. These shots undoubtedly appealed to Mr Penn’s talent for the histrionic as well as his political proclivities, but they only underline the picture’s political unseriousness. On one occasion, a torch-lit night-time scene in front of what looks like a monumental Mussolinian or Stalinist edifice, is obviously designed to look like a Nazi rally at Nuremberg. The camera catches Willie’s shadow, supposedly cast to several times life-size by the flickering torchlight on the massive structure behind him, and we are meant to think (I surmise) that the menacing shadow of fascism stalks the land.

The occasion is the dedication of a medical center.

It’s absurd, of course, but then attitude movies don’t have to make sense. Not making sense is rather the point of them. The carelessness with which they treat details of plot and characterization is typical of their cavalier disdain for humdrum, everyday reality. For instance, we are told that Willie is under impeachment from the legislature, but there is no mention of what he is being impeached for. It’s enough, I guess, to hint at a general atmosphere of corruption — even though the film also makes the familiar point that corruption is a way of life in Louisiana. The subtext is that corruption is a way of life everywhere, and this kind of cheap cynicism is enough to keep the narrator’s feelings of disillusionment front and center. More than half a century later, we can take such disillusionment for granted without any more specific motivations.

Likewise, we know that there is an estrangement between this disillusioned, self-hating narrator, a journalist named Jack Burden (Jude Law), and his lost love, Anne Stanton (Kate Winslet), but there is no explanation for it apart from a flashback scene in which, many years earlier, he had for no very persuasive reason, once refused her sexual advances. He tells her that the two of them have the future for sex, but apparently this future never happens. Why, we’re not told. It doesn’t add up. We have to take Jack’s unfulfilled longing on trust, which means that we also have to take it on trust that he will react as he does to the information that Anne is sleeping with Willie — a fact also unaccounted for. Is she just a power-groupie? She doesn’t remotely seem the type. But, again, the film doesn’t see the need to explain.

Her brother, Adam (Mark Ruffalo), is a portrait in pure attitude. A tortured saint and genius, he hates Willie as do all of his aristocratic connections, apart from Jack — who is too disillusioned to hate anybody. But then Adam seems to hate the whole world, including himself, as he hides himself away in a dingy flat and plays the piano. What’s wrong with Adam? The film has no ideas on the subject, apart from the suggestion that he is just too good and compassionate not to be in a state of constant pain at all the suffering in the world, since it is in order to alleviate this suffering that he swallows his objections to Willie and goes to work as director of the medical center. But he doesn’t have to like it. Again, disillusionment is presumably meant to be its own explanation.

When Adam gets his gun and goes after Willie, it is supposedly because he thinks Willie is trying to frame him to take the fall for corruption charges in relation to the Medical Center. The idea makes no sense but, OK, maybe Adam’s brains are scrambled by whatever it is that’s eating him. This motivation, such as it is, has to be supplied presumably because the only one Penn Warren mentions — the aristocratic Southern gentleman’s outrage at his sister’s “whoredom” by such a creature as Willie — wouldn’t seem enough to today’s audience. Why the sudden concern with supplying a plausible motivation — even though it’s not very plausible — when Mr Zaillian hasn’t bothered with any up until now? There must be some lingering sense left over from the old days when, as Hitchcock said, the soul of the cinema was plot, some sense that a set-up was required for the visually if not dramatically shocking dénouement which, like so much of the rest of the picture, self-consciously looks back to the cinematic techniques and appearances of the 1940s.

That there’s not more of this sense is further testimony to the fact that, nowadays, plot hardly matters. The soul of the cinema is attitude.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.