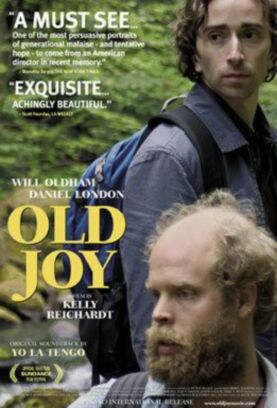

Old Joy

It’s an unfortunate coincidence for Kelly Reichardt and Jonathan Raymond, the director and the co-writer of Old Joy, that their film should be opening in the week after the latest flurry of rumors about the long-anticipated bankruptcy of Air America. That’s because the movie’s lush visual (Peter Sillen’s panoramic views of Oregon’s Cascade Mountains) and audio (a plangent musical score by Yo La Tengo) portrait of two aging hippies on a road trip to a rustic and deserted spa called Bagby Hot Springs is punctuated with left-wing political talk from Air America on the car radio. Is this just a lame attempt to add political content to what would otherwise be a minimally political scenario? Or is it designed in some way to compensate for the fact that nothing happens in the movie? There’s a drive in a car, some beer-drinking and joint-smoking, an overnight sleep under canvas, breakfast in a diner and then a bath in the hot spring water and a backrub. The two guys aren’t even talking about politics, though somebody is on the radio station they occasionally listen to.

At first you might think there was some ironic intent in this juxtaposition. You might almost believe that the edgy political monologue was intended as a commentary on the fecklessness and self-indulgence of the lifestyle-left in America, aspiring only to a hot bath in which to enjoy its bong and beer. At some level Ms Reichardt is attracted to this idea too. In her “Director’s Statement” she says that she received Mr Raymond’s “story of friendship” during the 2004 election campaign and thought it had “captured all the feeling of loss and alienation that everyone in my world seemed to be grappling with” — presumably as a result of the Bush victory. “Mark and Kurt’s relationship was, among other things,” she adds, “a great metaphor for the self-satisfied ineffectualness of the Left.”

Well, “metaphor” is not quite the right word there. “Example” would be better. But it is not a very good example. This is because she is unable to keep any ironic distance between herself and the two men. On the contrary, by falling in love with them and — in the spirit of their own (literally) touchy-feely reunion — giving them a big hug, the movie itself becomes another example of ineffectual self-satisfaction. Indeed, speaking as one who does not share its politics, I would say that the Air America bits — whose strident rhetoric was doubtless intended as a hard contrast to the softness in the two men’s relationship — were themselves yet another example of the same thing. The snatch of political talk we hear at the beginning, with its dark paranoia about right-wing conspiracy and deception, is indistinguishable from the snatch we hear at the end, as if the same person has been holding forth for two days — as if, unlike the elusive hot springs, the ceaseless flow of liberal grievance can be stepped into at any point with the same result.

Could it be that this self-pity and dull rhetorical predictability had something to do not only with the aforesaid “ineffectualness” but also with Air America’s failure to catch on — even as the putative majority, so we are told, share its disillusionment with President Bush and most of his policies? It’s not a question that interests the film-makers who, like their heroes, are far too wrapped up in their merely private vision of natural beauty and restored harmony between two friends representing two opposed tendencies within the lifestyle left.

Mark (Daniel London) is married and about to become a father for the first time. In an opening scene we see him and his put upon wife, Tanya (Tanya Smith), bickering like any bourgeois married couple, while a neighbor mows her lawn, about Mark’s projected expedition with Kurt (Will Oldham). “We know you’re going to go anyway, so I don’t know why we have to go through this thing of me letting you off the hook,” says Tanya peevishly.

“I won’t enjoy myself if you’re going to be miserable about it,” Mark replies, answering her passive aggression with more of the same.

Kurt, by contrast, is an untrammeled free spirit of the old hippie type: bearded, pot-smoking, always in search of the next high. Can these two be reconciled? Or, perhaps, can Kurt reassure Mark that he’s not a sell-out? Why anyone but Mark himself would care, I don’t know, but the film provides him with this reassurance, as Kurt tells him: “You’re so f****** brave. . .Having a kid is so for real.” He also tells him that his volunteer work in turning a dump into “a happening community garden” means that he has “really given something back to the community.”

“You could do it too,” says Mark. And then, catching himself: “It’s not that you don’t give to the community; it’s just a different community.”

Could it possibly be that the film intends us to take this nonsense seriously? I’m very much afraid that it could. But let’s give it the benefit of the doubt. Likewise to the film’s only other moment of humor, intended or otherwise, which comes in connection with Kurt’s theory that the universe is in the form of a teardrop falling through space. Physicists “don’t care about my theory,” he moans. “I don’t have any numbers for it.”

It may be that the laughter these lines inspire is deliberate, but they sound depressingly like the movie’s other examples of unfunny (and unprofound) hippie profundity, such as the observation that you can’t tell the forest from the city anymore because there are trees in the city and garbage in the forest — or the aphorism, which came to Kurt in a dream, that gives the movie its title: “Sorrow is nothing but worn-out joy.” That’s like saying pain is “nothing but” worn-out pleasure or death nothing but worn-out life: where it is true it is not interesting, and where it might otherwise be interesting it is not true. Actually, the funniest moment in the movie comes with the credits, among which we read the disclaimer that “Bagby Hot Springs does not allow nudity or alcohol.”

You notice that they don’t say anything about marijuana.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.