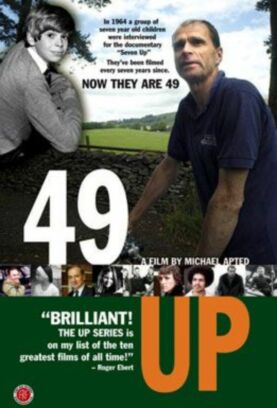

49-Up

This year I went to my high school class reunion. I’m not entirely sure why, but it was a hard thing to face for me and, apparently, for a great many of my classmates as well. Three quarters of them didn’t show up. It’s an indication of the extent to which we all tend to regard our past as a guilty secret, and those who have shared it as people to be avoided. Now just imagine that your past had been shared in documentary form with millions of others. That is the fate of Michael Apted’s subjects in 49-Up. Every seven years since 1964, he has come back to the same group of people his camera first encountered when they were seven years old. Now they’re 49. Not many of them have welcomed his return. In fact, like my high school classmates, many are refusing to participate. But let me just take this opportunity to say a big thank you to those who, however reluctantly, are still allowing Mr Apted to pry into their lives.

For the 7-Up series looks with each installment more and more like one of the most remarkable cinematic projects there has ever been. This is not only because of the intrinsic interest of the life stories it tells. Even more interesting are the reflections in those stories of slow-moving changes in our world that we might not otherwise notice. One of these is in the premiss of the series itself. Pretty obviously it owed its existence to a typically 1960s and British obsession with social class. Now that titanic mid-century struggle looks ever more like a non-event, while its familiar social divisions have given way to a unitary and post-modern celebrity culture. As one of these 49 year-olds says, the series now looks like a reality show from long before anyone had dreamed up such a thing.

The series of films was set up as a serious social experiment. Equal numbers of privileged and underprivileged children were chosen with a view (we may infer) to showing, as the years rolled by, how the British class system operated to exalt the first and cast down the second. Instead, as the years rolled by, class became an ever-diminishing factor in their lives and in their world. Now Tony, the East End cockney who became a cab-driver, has a lovely suburban villa in Essex but is semi-retired and spends most of his time at his holiday home in Spain. Sue, another cockney who went on to become a secretary is now an administrator at London University and looks forward to retiring to Cornwall with her second husband, Glen. She says she feels as if she has moved into the upper classes. Meanwhile Neil, a bright lad from Liverpool who went to university but dropped out, is still battling depression and living on government assistance as he has done for nearly the whole of his adult life.

Some of the privileged have of course done very well for themselves, but many have also had, like Neil, some kind of spiritual quest that has diminished their career prospects. Bruce, shown at age 14 saying that at the posh St. Paul’s School “they didn’t enforce being upper class,” studied mathematics at Oxford but then went off to teach among the poor in the East End of London and in Bangladesh. Now, having married late and started a family only in the last seven years, he is a defiant sell-out, teaching at the private St. Alban’s School where the work is so much more satisfying and the pupils of a much higher academic level than in the East End. When he was teaching there, he says, he thought his good influence would act on his pupils like water dripping on a stone. Instead the water drip of their academic dullness and indifference wore him away.

Looking at the original film now, Bruce can hardly recognize himself at age seven. That child looks so lost to him, he says. Cue his seven-year-old self at boarding school saying to the camera: “My heart’s desire is to see my daddy” — who was 6000 miles away. It’s enough to break your heart all over again. Small wonder he is surprised to be so happy and content a father himself all these years later. His life is one of several which illustrates the general proposition that the focus of the –Up films has tended to shift away from work and money and social class and towards marriage and family. More and more, what unites these people across their class boundaries, making all other considerations seem minor — and what moves us again and again about 49-Up — is their still undiminished heart’s desire to be happy in love.

For a surprising number, the wish has come true. Next to Tony, perhaps, the most attractive of all is Suzy, the upper-class girl who is shown again — as she has been in each of the last four films — looking morose and chain-smoking at age 21 as she tells the camera that she is very, very cynical about marriage and children. And once again, too, we see her seven years later absolutely transformed into a lovely and radiant young woman. “What happened to you?” the Michael Apted of 21 years ago asks in astonishment. The answer then was Rupert, her husband, and it still is. Suzy and Rupert are as happily married as ever, and one suspects that it is partly on his account that she seems to grow prettier and younger-looking with each new installment. Yet she tells us that, with this film, “For the first time I actually feel happy in my own skin.”

Unfortunately, she also tells us that being interviewed for these films is “very difficult, very painful, not pleasant in any way,” adding that: “This is me. Hopefully, I shall reach my half century next year and bow out.” Her beauty and charm make this prospective decision not to take part anymore all the more regrettable, but everyone who expresses an opinion on the subject seems to feel more or less the same way, putting the future of the series in doubt. “Every seven years a little pill of poison,” says one of them, I imagine in the spirit of my class reunion’s numerous no-shows. And even if they don’t all quit on us, Michael Apted himself is now 65. How much longer can the series continue? Let’s hope that he has many years yet to be making movies and that, out of public-spiritedness and in spite of their dislike of it, those charming seven-year-olds of 1964 will soldier on, cinematically, at least until they reach the Biblical three-score and ten.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.