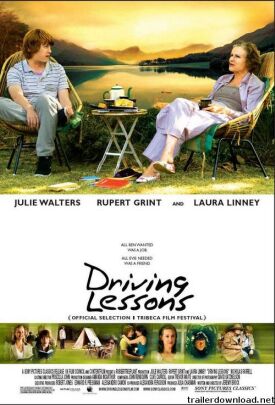

Driving Lessons

Driving Lessons at its best is a charming, funny and sometimes touching family drama starring Julie Walters and Rupert Grint of the Harry Potter films, now brought together again by writer and director, Jeremy Brock. Too bad it’s not more often at its best. Mr Grint plays Ben, the 17-year-old son of a priest of the Church of England (Nicholas Farrell) and a domineering mother (Laura Linney) who is supposed to be giving Ben driving lessons but who uses these as a pretext for carrying on an affair with another priest (Oliver Milburn). Ben goes to a Christian school and is himself a believing Christian, but he is becoming more and more troubled by his mother’s behavior and by the inability of his meek and mild father to stand up to her. “Sometimes,” says dad after a particularly vicious put-down by his wife, “your mother can be a little —” but then he trails off and goes back to his bird book.

For her part, mother is a sanctimonious moralizer whose strictness with Ben is a sort of compensation for her own moral laxness. An inveterate doer of good deeds, presumably as a cover for her bad ones, she has strong opinions about everyone and everything. When she berates Ben for coming home late, he says: “There was no place to call from. If I had a mobile —”

“Mobiles give you cancer,” snaps mum.

Ben finds a part-time job as a home-help to an old lady called Evie (Miss Walters), who is (or was) an actress and who Ben thinks is one of the grand dames of the English stage. Evie’s sometimes-endearing, sometimes-scary eccentricities are meant as a contrast with Miss Linney’s monster-mum, the religious believer who is as phony as Evie the actress is genuine. The problem is that both women are made into caricatures by the comparison, the Wicked Witch and the Good Witch of this North London Oz. To some extent it doesn’t matter because Ben, like Dorothy, is really the focus of our attention. The two women are just his terrifyingly opposed, 17-year-old fantasies of female adulthood — fantasies which are finally tamed and rendered harmless with the help of an obliging Scottish lass called Bryony (Michelle Duncan). At least we are encouraged to think so when Ben, having been cowed into playing the part of a tree in his mother’s latest Sunday School pageant, finally rebels against her: “I don’t want to be a tree no more. I’m gonna be a man.”

Well, good for you, dear, but that is rather what we expected of you. The young man with “the soul of a poet” who is damaged into sensitivity by either weak or dominating parents — or, in Ben’s case, by one of each — is a cliché that goes back to the 1950s and movies like Rebel Without a Cause or Tea and Sympathy. It looks out of place in the context of the 21st century’s model of solicitous parenting, relentlessly dedicated to the offspring’s self-fulfilment rather than some abstract model of ideal behavior. Driving Lessons’s attempt to meet the dramatic need for an old-fashioned, oppressive home life by adopting a more recent movie cliché, that of the vicious, stupid or hypocritical religious believer, strikes me as rather a desperate measure. Certainly, mothers like Ben’s are very far from being the norm in what I know of contemporary London.

Moreover, she is potentially a much more interesting character than Mr Brock allows her to be. Among her good deeds, for instance, is inviting into the family’s home a clearly insane person, Mr Fincham (Jim Norton), who ran over his wife with a car. There seems no ulterior motive behind her wish “to help him in his recovery,” so what is it about? Good deeds ought to be taken seriously, especially the crazy ones, but Mr Fincham is only a running gag. “You may have noticed that Mr Fincham is dressing in my clothes,” says mother to Ben one day when he comes home. “It’s part of his recovery.” Likewise, I would find it a lot more interesting if it were something more than just one more instance of mum’s hypocrisy when she says to her son: “Whatever happens behind these walls, Ben, we’re God’s ambassadors. We show the world a smiling face.” This is not a contemptible impulse.

There are, of course, many more human touches to Miss Walters’s Evie. Her attempts to manipulate Ben look much more real than his mother’s tyranny, and when he is browbeaten into taking her to a poetry reading in Edinburgh, we can’t resist the poignancy of his discovery that, so far from being a grand dame, Evie’s most famous role was on a daytime soap opera during the 1980s called “Shipping Magnates.” Tactlessly, Bryony greets her by gushing: “I know all your catch phrases: ‘I’m a woman, not an oil tanker.’ You’re huge on the gay scene.”

“Am I?” she replies weakly. She then has to explain to Ben: “I don’t suppose you’re familiar with the idea of kitsch?”

I think she means camp but, either way, Ben is allowed to preserve his non-kitschy, non-campy illusions about her and so to stake his claim to being the poet that she believes him to be. There is a nice irony in the fact that Julie Walters really is one of the grand dames of the English stage, or at least of the British film industry — though as yet Her Majesty has only seen fit to award her the Order of the British Empire, and not to make her an (official) Dame. Though she is only 56, her performance here as a woman who must be at least 70 may finally put her over the top.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.