Aura, The

The Aura begins with a shot of a man (Ricardo Darín) suspended against a white background. Something is beeping. As the camera pulls back and the image is turned right side up, we realize that he is lying, apparently asleep or dead, on a white tile floor. After a minute or two, he opens his eyes and looks around him as if he knows no more about where he is than we do. Then the camera pulls back still further to reveal to us — at the same time he himself realizes it — that he is in the lobby of a bank in front of an ATM. He picks himself up, takes some cash from the machine and walks out. Cut to the opening credits and the same man, a taxidermist, in his workshop preparing the disassembled body of a fox for display in a museum in Buenos Aires. The process is there for us to observe in some detail, still wordlessly. Someone, seemingly a woman, stands outside the room where he is working, trying to get in. He ignores her.

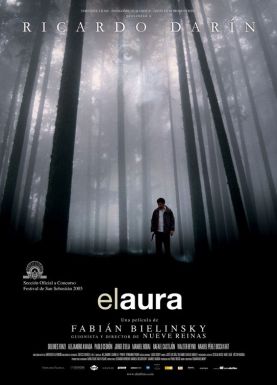

It’s a virtuoso bit of film-making to draw us in. What happened to the man in the bank? Was he mugged? If so, why didn’t he seem surprised or angry or show any sign of injury? And why was the cash — was it even his? — still in the machine? Then, what does the absorbing work of taxidermy have to do with the bank episode? Who is the woman outside his door and why does he not seem to notice her. The Aura is the second feature by the Argentine director, Fabián Bielinsky. It is also the last — and it shows us as much as his first film, the enthralling Nine Queens of 2000, how much we have lost with his tragically early death from a heart attack last June, aged only 47.

Eventually we learn that the hero, who appears in the credits only as “the taxidermist,” is epileptic and that the film’s title refers to the moment before an epileptic seizure when “everything stands still and a door opens in your head and lets things in. . .There is nothing you can do to stop it. You’re free: no options, no choice, nothing for you to decide. Things narrow and you surrender yourself.” There is an analogous moment, I think, later in the film when he has a gun pointed at him, and again when he is pointing a gun at someone else. The idea seems to be that there is something mystical and rather addictive about such moments of frozen time — something revelatory, too, and associated in some way with the taxidermist’s photographic memory.

This comes up when the dialogue and the drama begin, as he is standing with a friend called Sontag (Alejandro Awada), another taxidermist, at the museum and watching security guards handling bags of money. His memory, intelligence and skill at planning would enable him to commit the perfect crime, he tells the skeptical Sontag, who tests him by asking him to repeat the serial numbers on the money bags without looking. He does so. Idle chitchat. But when he and Sontag go on a hunting trip, the taxidermist accidentally shoots and kills a man named Dietrich (Manuel Rodal) who, as he discovers, has been planning just such a robbery, of an armored car, as he had described to Sontag. Without quite making a conscious decision to do so, he finds himself taking over this other man’s perfect crime.

But to the intellectual demands involved in the planning there are now added the additional difficulties of working out from Dietrich’s fragmentary notes the details of the plan and, when a couple of hard-case accomplices (Walter Reyno and Pablo Cedrón) turn up, persuading them that he was in on the job from the start and that Dietrich has been called away, leaving him in charge. In the midst of this increasingly intricate plot, so dependent on perfect timing, we are constantly reminded of the possibility of another seizure, which finally comes at the very moment when the robbery is about to begin and the hero has learned of a serious mistake in his planning.

There is also a sub-theme, which doesn’t quite rise to the level of a sub-plot, concerning the treatment of women and animals that goes back to the scene in the taxidermy workshop with the woman outside the door. The taxidermist doesn’t like killing animals, but goes on the hunting trip anyway when his wife, who was presumably the woman at the door, leaves him. He and Sontag split up after he taunts the latter for being a wife-beater. It turns out that Dietrich’s much younger wife, Diana (Dolores Fonzi), is also the victim of abuse and terrified that her husband will return. Our hero wants to tell her that she is free of him but cannot do so without endangering the heist. Dietrich’s wolf-like dog is constantly haunting the successors to his plot as if it were his ghost.

All in all it is a very strange and atmospheric film, full of the bleakness and savagery of the Patagonian landscape but also of wonder at human ingenuity. Like the taxidermist, we are thrown into the middle of a complicated and sinister story and have to work out what is going on. Like him, too, we seem for the moment to have mesmeric powers of concentration and to transcend, for the moment, the moral dimension of what he is doing. In the end the intellectual exercise is meant to be seen as all that there is, and the money is left sitting irrelevantly in the armored car like the money in the ATM at the beginning. It’s the perfect ending to a nearly perfect film. What a pity that it is the last we shall get from Fabián Bielinsky.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.