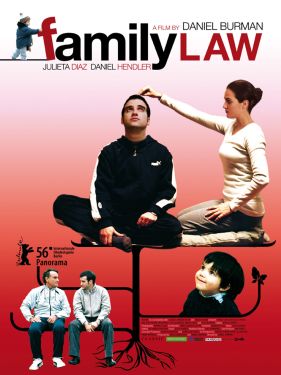

Derecho de Familia (Family Law)

If you’ve seen The Lost Embrace (El Abrazo Partido) of 2004 by the young Argentine director Daniel Burman, your first reaction to his new film, Family Law (Derecho de Familia), is likely to be that we have been there, done that. Like the earlier picture, this one is about the troubled relationship between a Jewish father and son in Buenos Aires and how the gap between them is — more or less — bridged. Yet I, at least, never had the feeling that Mr Burman was repeating himself. Instead, he carries the theme of Lost Embrace a stage further in Family Law. Before, that is, Mr Burman’s interest was in that significant moment in life when children recognize that their parents are human beings like themselves who have had, sometimes instructively, many of the same experiences. The life passage marked by his hugely likeable new film is the much scarier moment when they recognize that they’re becoming their parents.

Or, more accurately, it is about a son who is happily living a life that he imagines is quite different from his father’s when he realizes that some combination of genetics, love and family circumstance is inviting him to be more like his father than he could ever have imagined he might be — in effect, to become his replacement. He should have known. Both men are known to everyone, even their nearest and dearest, as Perelman. Their Jewishness, like the fact that both are lawyers, is meant to be seen as drawing them together, yet the differences between them seem much greater than the similarities.

Perelman Sr (Arturo Goetz) is a lawyer in private practice. A widower, he has a personal and probably intimate relationship with his secretary, Norita (Adriana Aizemberg), though Perelman Jr. (Daniel Hendler) seems remarkably uncurious about his father’s personal life or relationships apart from a brief scene in which we are introduced to some comical uncles. Much of the film consists of voiceover narration by the son, who describes the life lived by his father as a collection of odd quirks and foibles unconnected to himself except for the old man’s disappointed hope that his son would join his practice. “A Zelig among lawyers,” Perelman Jr. tells us, Perelman Sr. takes on the vocal characteristics and even the mannerisms of whomever he is speaking to. He likes to know a little something about the trade or profession of all his clients. Some of them he meets only in his ramshackle office; some only in his favorite café. By unknown means he has arranged things so that he never has to stand in line.

All these things are described by Perelman Jr. with humorous detachment, as if his father were nothing but an amusing eccentric he had met. He himself is a law professor at the university, specializing in legal ethics, with no interest in his father’s practice, which he sees as being tinged with the small corruptions that seem to be taken for granted by the rest of the legal profession. Though passionate about teaching, Perelman Jr. is a rather solitary figure in contrast to his father, who seems to have friends wherever he goes, and he is so much devoted to his work that he seems to have no life outside it. His suit seems to be a kind of security blanket to him, and he often sleeps in it.

Things begin to change for him as he recounts his courtship of one of his law students, a Pilates instructor called Sandra (Julieta Díaz). So attracted to her is he that he buys what appear to be the first casual clothes he has ever owned, a track suit, so as to take Pilates lessons from her. The comic consequences can be imagined. But Sandra is served with a legal order to cease and desist, since she is not a licensed instructor in the Pilates method — she had thought that it was like teaching swimming or the piccolo — and her equipment is confiscated. Perelman Jr. offers to help with her legal defense, but as he is lacking in practical experience with the law, his father does most of the work for him. When she wins the right to carry on with her business, he allows her to think that her gratitude is owed to him.

They marry and have a child, but the film skips over that part of their lives until we rejoin them at the point where Perelman Jr. is making fumbling efforts to be a good father to four-year-old Gastón (Eloy Burman). These coincide with a month’s enforced layoff from his university job which has hitherto been so absorbing that he is practically a stranger to the boy. As he begins to involve himself more and more in his son’s life, he finds that his own father is involving himself more and more in his. There is, therefore, a nice symmetry running through the final half of the film as Perelman Jr has to define himself both as a father with respect to his son and as a son with respect to his father.

Mr Burman’s picture stops short of the point at which any life-changing decisions might or might not be made. It is enough for him to show his hero at the moment when the acceptance of his place in the progression of generations has ceased to hold any terrors for him. This comes when Perelman Jr., having accepted responsibility for costuming the children in a school concert at the Swiss nursery school his son attends, beams with pleasure when little Gastón and all his friends appear on stage in full lawyer gear, complete with miniature briefcases, as their teachers yodel in the background. “He can look like his father whenever he wants,” remarks the proud papa himself. “If he wants. What’s the hurry?”

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.