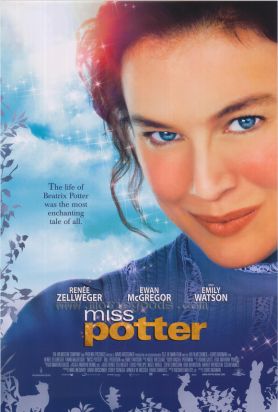

Miss Potter

“Life is just one damned thing after another,” said Elbert Hubbard, the early 20th century bellettrist and author of the once-famous “Message to Garcia.” He must have reflected ruefully on his own wisdom as he went down on that notoriously damned thing, the ocean liner Lusitania, sunk by a German U-Boat when he was on his way to Europe to try to make peace in the middle of World War I. But he was also right in the sense that this relentless eventfulness is the primary way in which life differs from art, which demands a certain economy with events in order that they may be given some shape and thematic unity — things that are sometimes a bit hard to come by in biopics like the charming Miss Potter. Directed by Chris Noonan from a screenplay by Richard Maltby Jr., the film tends to come up short in the shaping and unity department and so to seem, like life itself, just one damned thing after another.

True, on the plus side, this disjointedness is redolent of reality, but watching it on the big screen can be fatiguing. Fortunately Messrs Noonan and Maltby have the luminous Renée Zellweger to work with in the principal role and, to my admittedly admiring eye, this makes up for an awful lot. They also have going for them the near-universal popularity of her character, Beatrix Potter, whose exquisitely illustrated little square volumes dealing with the adventures of Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny Mrs Tiggy-winkle and the naughty Squirrel Nutkin and so many more are fondly remembered remnants of childhood for so many. Yet there is little in the movie about these characters or their creation apart from the fact that, as we already know, many people admire them.

The other problem you may have when making a film about real people is that it’s harder to avoid cliché. Miss Potter’s battle against her parents’ class prejudice in order to marry the man she loved, as shown in the film, suffers from the double whammy of being both much too familiar as a theme of old-fashioned books and at the same time virtually incomprehensible to today’s audiences, since the man, her publisher Norman Warne (Ewan McGregor), is from virtually the same social class as she is — as she indignantly points out to her parents. That the big difficulty, so far as they are concerned, is that he is “in trade” while they are professionals with inherited wealth must be particularly baffling to Americans.

Yet in spite of this, the human attachment of these two shy and rather nerdy Britons of a century ago still has an emotional punch to it. At least part of the reason is the film’s success at imaginatively re-creating the moral world — as well as, to my eye and barring the pollution, the physical world — of Edwardian England. It’s not just that social class is openly and immensely important to people. That’s an inert datum because it answers to nothing in most of us today. It’s rather that the idea of romantic love — which we still have in theory but which sexual freedom has robbed of much of its imaginative power — is brought almost shockingly to life again in this respectful re-creation of life before the sexual revolution.

Or, I should say, the first sexual revolution: the one that took place in the 1920s and foreshadowed the much more sweeping and lasting one of the 1960s. When love comes after so much shyness and repression and parental thwarting, it takes on a force that we seldom see these days — a force naturally increased by its subsequent encounter with tragedy. Yet the very strength of that narrative arc makes such other and characteristically biopic elements as Beatrix’s imaginative world as revealed in her books or her efforts with the money they generate to preserve the wild and rustic character of the Lake District look almost like irrelevancies. What are they doing here? Oh, right. They really happened.

Well, other things happened too — things of which the movie makes no mention. Particularly conspicuous by its absence is any mention of Miss Potter’s shrewdness as a businesswoman, as shown in her pioneering efforts to transform the popularity of her creations into profitable toys, knick-knacks, gewgaws and household goods long before Disney and others thought they were inventing the merchandising of entertainment-generated brand names. I was also dismayed by the mercifully few bits of animation, where the familiar drawings come to life on screen as a way of showing how alive they were to their creatrix, Beatrix. Not only do these make the movie look, to my eye, slightly cheesy and fantastical, they spoil the period feel that is otherwise its great virtue. Nowadays, we may think it sweet and endearing to think talking animals are real; at the time this would have looked like mental illness.

Most unfortunate, I think, are the film’s attempts to give its disjointed narrative a central theme in the form of that too-familiar triumph over the patriarchy of everything small, feminine, individualistic, personal, fantastical, artistic and environmentally correct. The movie could have done, perhaps, with just a little emotional distance from the heroine and her twee world. On the other hand, there is a distance from Amelia, “Milly,” Warne (Emily Watson) an early feminist who hymns the joys of a single woman’s life — “Men are good only for two things, financial support and procreation” — and eschews those two terrors, “domestic enslavement and childbirth,” until Beatrix asks her what to do about her brother’s proposal and she reveals the romantic heart beneath her militant surface.

In spite of its shortcomings, I enjoyed the movie quite a lot. Generally speaking, it was nicely done, offering us real-looking, sympathetic characters, some spectacular scenery and, above all, a sense of history as it must have been lived a century ago — no small achievement for any film.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.