Time on the Cross of Hype

From The New CriterionWhere were you and what were you doing when you heard that Anna Nicole Smith had died? Philip Kennicott led off one of his hugely portentous big-think pieces for the Washington Post’s Style section — “The Fantasy of Happily Ever After: Anna Nicole Smith Stripped Marriage of Its Illusions” as the headline writer put it with happy absurdity — by calling this an office joke, but the joke was on him. That is, it wasn’t a joke at all. People really will remember getting the news the way they remember the moment when they first heard that President Kennedy or Martin Luther King had been shot — or, I like to think, the way I remember the moment when it first dawned on me that the popular celebrity culture, having been quietly buying up shares in the hitherto dominant and supposedly serious media culture, had successfully launched its takeover bid.

It was one day in January of 1994, not long after I started writing this monthly meditation on the media. I was making myself some lunch as the sun came streaming in through the kitchen windows. When I turned on the ABC radio news at the top of the hour, the lead item was the latest in the Tonya Harding-Nancy Kerrigan scandal. You remember that one, don’t you? Aspiring Olympian figure-skater (Tonya) has her ex-husband, one Jeff Gillooly, hire a thug to whack her rival (Nancy) on the knee with a metal rod? Ring any bells? Miss Harding later took on and defeated Paula Jones in a celebrity boxing match on Fox. Anyway, I remember muttering to myself under my breath, “What on earth is that doing there?” Yet, even as I said it, I somehow knew the answer. We were living in a different world, and here was the proof of it. It was a post-Cold War, end-of-history sort of world which, before the year was out, would see “the trial of the century” of a former football star and minor celebrity for the murder of his wife and, before the decade was out, the dawning of celebrity-hood not only for Miss Jones but also for Miss Monica Lewinsky and the extra-marital sexual practices of the President of the United States.

In short, it was a world in which celebrity gossip would move out of the shadows and dominate both politics and the media. Celebrities are the famous people we feel we know. Of course we do not know them. The people who forget that this familiarity is entirely an illusion, carefully fostered by the media in collaboration with the celebrities themselves, may become madmen and pests — sometimes stalkers and assassins. But the media create the illusion because it justifies their own existence as the Illuminati, a gnostic élite who know the truths that lie behind and beneath the public shows of fame and who can bring that information to market. In the wake of Mrs Smith’s death, The New York Times thought nothing of running a business section story on the changes it had brought to light in the commodity market in celebrity gossip. Poor People magazine had been caught flat-footed going large on the Astronaut Love-Triangle story in the issue that was just hitting the news-stands when the Anna Nicole story broke.

Not that People’s story wasn’t a great one. Captain Lisa Nowak, U.S.N., who flew on the Space Shuttle last year, went to the Space Station and walked in space, had finally spaced out. She put on diapers (so that she wouldn’t have to make any rest stops) and drove across country from Houston to Orlando allegedly to kidnap or murder her fellow astronaut, Captain Colleen Shipman, U.S.A.F., whom she supposed to be her rival for the affections of a third astronaut, Cdr William “Bill” Oefelein, U.S.N. In any other week that story would have been a big seller for a gossip magazine, but not this week. Anna Nicole’s death blew it out of the water, and a lumbering media dinosaur like People couldn’t adapt in time. “The print traffic jam illustrates the larger problems facing the celebrity-news industry,” wrote Maria Aspan for the Times: “especially the tenuous success of newsweeklies like People, Us Weekly, Star and The National Enquirer. Before the explosion of Internet news and gossip blogs, People and its competitors would have dominated the nontelevision Anna Nicole coverage.”

Unfortunately for Time-Warner and the rest of Big Media, that is no longer the case, and People, already suffering, like other publications of the Time-Warner corporate parent, from cutbacks to its journalistic staff, must be regarded as being weakened still further. Yet it’s an ill wind that blows nobody any good. Ms Aspan writes: “Perhaps the most unusual side effect of the surge in online celebrity gossip is a newfound appreciation for restraint in print and televised celebrity news.” Restraint? A misprint, surely? But no, her interviewees from People, US Weekly and “Access Hollywood” all agree in expressing “caution about overplaying the Anna Nicole coverage.” Restraint can also be good business, apparently. “I’m hoping that we’re the first ones to jump out of this when there’s nothing new really to report,” says Rob Silverstein, the man from “Access Hollywood,” adding that “I’m trying to get out of it first.”

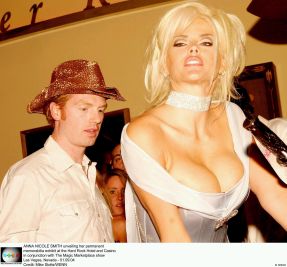

But why was the Anna Nicole story so much more compelling than Lisa Nowak’s? Because astronauts are a dime a dozen compared to someone like Anna Nicole, who was already a bona fide celebrity and whose death, therefore, spectacularly advanced her story. The media’s natural tendency to refer to her by her made-up forenames alone — she had been born Vicki Lynn Hogan — was an example of that feeling of false intimacy which is the hallmark of the celebrity culture. She had become familiar to us through her career as a stripper, Playboy’s Playmate of the Year for 1993, wife (briefly) to a Texas billionaire more than three times her own age and, after his death, a litigant for the half of his fortune she claimed to have been promised. Latterly, she had parlayed this already-interesting story into a highly paid modeling career, a “reality” TV show and another spell as the cynosure of the gossip press last year when Daniel, her 20 year-old-son by her first husband, Billy Wayne Smith, visited her in the hospital room where she had just given birth to his half-sister and promptly expired from a mixture of methadone and anti-depressants.

Subsequently she had managed to remain in the news when there emerged a rival claimant to the paternity of her new-born daughter, which she had attributed to her lawyer and handler, Howard K. Stern. After her death, a third would be father came forward in the shape of Zsa Zsa Gabor’s ninth husband, who styles himself Frédéric, Prinz von Anhalt, while the late Mrs Smith’s half-sister, Donna Hogan managed to drum up some publicity for her book (Train Wreck: Anna Nicole Unauthorized) by claiming that the child might have been the product of the billionaire’s frozen sperm, carefully preserved by her sister for more than a decade. And, then, as if all that wasn’t enough to keep interest on the boil, an autopsy initially failed to find the cause of death and so left the field wide open to speculation on that subject. If I were Rob Silverstein, I wouldn’t be too quick to “jump out” of the coverage on this story.

It is a good illustration of how the celebrity culture operates by making celebrities seem familiar to us — rather like the most popular kids in high school — so that we will care whom they are dating or marrying or divorcing or feuding with — or what they are dying from. When such information about their private lives becomes public, they are of course no longer private, but we cling to the fantasy that we are being given exclusive glimpses into secrets we were not meant to know. And the celebrities seem to confirm the fantasy as reality when they plead to be allowed to live their private lives without interference from the media. The fact that the publicity business — which extends ever more widely into the media than People magazine and “Access Hollywood” — is all an elaborate charade remains stubbornly unaffected by the fact that many of those who have made their fortunes by it feel genuinely aggrieved they have not been able to do so without losing their right to a private life.

In fact, their sufferings through the attentions of the media, or the paparazzi, easily become part of the legend, as they did in the case of the late Princess Diana. Public suffering or other strong feelings are of the essence in celebrity-making, and the media are not inclined to stand on their dignity — even if they had any — when it comes to exploiting even the travails that they themselves have caused as a way of milking every last drop of pathos out of the not-so-secret sufferings of those they have elevated to the pantheon of celebrityhood. Anna Nicole Smith, though she wasn’t born Anna Nicole, was born to this pop cultural royalty. Or rather, she wasn’t — since, as the New York Times reported, she had made up the story of her impoverished, small town upbringing in Mexia, Texas, along with her names. She actually grew up in Houston. “Mom,” her mother reported her as saying. “nobody wants to read books or see people on TV concerning, you know, middle-class girl found a rich millionaire and married him. There’s not a story in that. . . .She said, ‘The story is I come from rags to riches, and so that’s what I’m going to tell.’”

It was also what the media were going to tell, since of course their interest in a good story was as strong as hers. “I know we are not supposed to feel much admiration for 26-year-old bottle blondes who marry ancient millionaires,” wrote India Knight in the London Sunday Times, “but I don’t see what’s so terribly wrong with it. If I’d been a dirt poor, child bride, chicken shack waitress from the wrong side of the tracks I could think of worse things to do with my time. . . The odds were stacked against her.” Mr Kennicott’s piece in the Washington Post had taken, after a learned cultural tour d’horizon on the history of the courtesan, much the same course: “For as much as she was a figure of fun, a goddess of tabloid abundance, the shock of her death at 39 was far bigger than that of just any celebrity. She had gotten under our skin, and taken on a role we didn’t quite realize was so big in the history of marriage, money and sex. . . When Anna Nicole Smith, a voluptuous 26-year-old Playboy Playmate, married an octogenarian oil-rich billionaire, she crossed a line, assuming too high a place in our supposedly mobile society.”

Ah! There you have it, the mythic moment. Like Icarus, it seems, she had soared too high, too near the sun, and the inevitable consequence ensued. “Society took its revenge,” wrote the Post’s essayist, “confining her to gossip magazines and scandal sheets, foreclosing her appearance in the black-and-white party photos of respectable magazines, where trophy brides appear smiling and dazzling with their balding, sagging, tremendously rich husbands.” Hang on a minute! “Society”? Society? If we still had “society” we’d also, presumably, have the courtesans whose disappearance Mr Kennicott laments — and the discretion that differentiates them so spectacularly from Anna Nicole Smith. “Society” has gone the way of respectable magazines, or respectability itself for that matter, for I know of none that thought themselves too respectable to participate in the orgy of publicity that was her life. What could be more respectable than The Washington Post itself? Yet here it was, as obsessed as anyone else with the woman while pretending to look down its aristocratic nose at a set of disapproving bourgeois standards that are alleged to have ruined her life long after they have vanished from everyone else’s.

It is a reminder of the extent to which the mythologization of the celebrity, and the saga of his — or, especially, her — sufferings, depends on the pretense that this lost world of prudery and sexual self-righteousness and moral disdain for arrivistes like Anna Nicole still exists to cause those sufferings. The sense of mystery that people like Mr Kennicott attribute to her is equally manufactured. “We never really knew what motivated Anna Nicole Smith’s marriage,” he writes preposterously. “Perhaps it wasn’t so crass and calculating as it seemed from the outside.” Then, again, perhaps it was. No matter. The point is that “she was clearly unhappy.”

Now she seems merely a sad and pathetic creature, rather like her forebears in the world of courtesans, Manon (Abbe Prevost’s doomed courtesan) and Violetta (Verdi’s hooker with a heart of gold) and Proust’s Odette. We are at the end of the opera, the wandering woman is dead, and now the clown is the victim. Neither category really does her justice, and so the false tears and moral clucking will sound together — a reminder that we have eliminated yet another sexual category that allowed for contradiction and ambiguity.

Who is this “we” who have eliminated “yet another sexual category”? And what are the other sexual categories that have been eliminated? I have been under the impression, perhaps mistaken, that sexual categories, so far from being eliminated, have been multiplying during my adult lifetime — and that there are few to none of them that do not allow for contradiction and ambiguity. In fact, contradiction and ambiguity — as in the new categories of the “transgendered” — are the very things that create these categories. All this is just words, but words designed to do a particular job of mythologization that can be done in other ways. Thus, when the ever-reliable significance-hunter and director of the Center for the Study of Popular Television at Syracuse University, Robert Thompson was asked by the Post for his views, he replied: “If I had to say what was Anna Nicole Smith’s legacy to the culture, I’d call her a conceptual artist. . . It was almost like she was this explorer who went out to the edges of celebrity and by watching what she was able to achieve, we know more about the nature of celebrity.”

So it is possible to become a celebrity merely by showing us “more about the nature of celebrity”? This seems impossibly circular, like Daniel Boorstin’s line that a celebrity is “a person who is known for his well-knownness.” This is one of the two things — the other is Andy Warhol’s dictum about how, in the future, everybody will be famous for 15 minutes — that everyone knows about celebrity. Naturally, therefore it appeared — unattributed and in mangled form — in the lead of the New York Times’s report of Mrs Smith’s death: “Anna Nicole Smith, a former Playboy centerfold, actress and television personality who was famous, above all, for being famous, but also for being sporadically rich and chronically litigious, was found dead on Thursday in her suite at the Seminole Hard Rock Cafe Hotel and Casino in Hollywood, Fla.” Clearly, Boorstin’s aphorism is now itself famous for being famous, but it seems to me patently untrue, at least in Anna Nicole’s case. She was famous for her abundant female attributes and her shameless willingness to trade on them, and on a luridly publicized private life, precisely in order to gain fame — and, of course, wealth.

In other words, like most genuine celebrities — as much an oxymoron as “reality TV” — what Mrs Smith was famous for was not being famous but honesty. At least she was if it is, as widely supposed, a form of honesty to make your life perspicuous to the prurient interests of the media and the public. I have some doubts about this. Though the bread and butter of the media themselves depend on this assumption, it seems to me to be based on the dubious notion that the public display of strong feelings and blatant forms of immoral and self-indulgent behavior are, like public suffering, infallible indicators of the personal authenticity that we seek from the celebrity. Dubious or not, however, it is now becoming as much a part of our political life as it is of the demi-monde inhabited by the likes of Tonya Harding and Anna Nicole Smith. The only event on the national stage to rival the news of the latter’s death in the days immediately after it was the announcement of the candidacy for president of Senator Barack Obama of Illinois — unquestionably the nearest thing to a pure celebrity ever to aspire seriously to that office.

Frank Rich of The New York Times even made it a test of that seriousness — which could not really have been in doubt — to see “if he has the star power to upstage Anna Nicole Smith.” Yes, that sounds like the quality we want in a national leader after the dark years of what Mr Rich calls “the Cheney-Lieberman axis of neo-McCarthyism.” That “neo-McCarthyism,” by the way, is the political equivalent of Anna Nicole’s hardscrabble upbringing in her tiny Texas town: an essential part of the media mythology by which our celebrity hero is brought to the point of his celebrity triumph as described by Mr Rich in the following richly evocative sentence: “Now that Mr. Obama has passed through Men’s Vogue, among other stations of a best-selling author’s cross of hype, he wants to move past the dumb phase of Obamamania.” Like Princess Diana’s, it appears, the Senator’s Christ-like sufferings are not just hyped, they are the hype. I wonder if it can be possible that the world has changed as much as it would take to elect such a perfect media-martyr as this as our president? Well, we have nearly two years of hard campaigning ahead of us in which to find out.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.