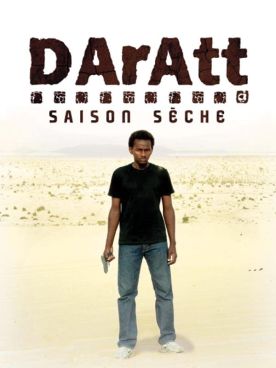

Daratt

Michael Novak, the scholar and theologian, points to a particular medieval story — best known to English speakers as Chaucer’s Tale of Melibee from The Canterbury Tales — as the cornerstone of modern liberal society. In the story, a man seeking revenge for terrible wrongs finally has his enemies in his power, but he is prevailed upon by his wife not to take vengeance. If Professor Novak is right, we should take Daratt (or “Dry Season”) by the Chadian director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun as being among the more hopeful artifacts to come out of the Islamic world in recent years.

As we have learned in Iraq, the sort of tribal society in which the vendetta and other sorts of “honor killing” are still commonplace is unpromising ground for democracy and liberal values to take root in. The civil war in Chad makes the one in Iraq — if that’s what it is — look like a brief fracas. Continuing on and off more or less since the French left in1960, it has claimed uncounted tens of thousands of victims, including members of the director’s family. His film takes this war as its setting.

It begins during one of the periodic lulls in the fighting, when a government “Commission on Truth and Justice” announces an amnesty for 200 war criminals. This produces riots and demonstrations. “The blood our families shed must be paid back!” says a rioter. In one of the opening scenes, 16-year old Atim Abatcha (Ali Bacha Barka ), hears the noise of an angry crowd, then the sounds of a machine gun firing and panic off-screen. He then wanders into the village square where the crowd has been. It is now deserted except for the shoes and sandals lying everywhere which have been left behind by people in a hurry to get away.

Atim is himself not obviously politically involved, but his blind grandfather Oumar Abatcha (Khayar Oumar Defallah) summons him to tell him that, in the absence of justice from the state, the boy is going to have to take vengeance against his father’s murderer. He carefully unwraps an automatic pistol and presents it to him. “This belonged to your father,” he tells him. “It has not been used for a long time.” He also warns him that the man he must kill, Nassara (Youssouf Djaoro), is a dangerous character. Then he sends the boy off to the capital, N’Djaména, to find him.

I particularly liked the way in which Atim is at first just like any country boy arriving in the big city for the first time. He is soon befriended by Moussa (Djibril Ibrahim), who offers him a place to stay with his, Moussa’s, aunt (Fatimé Hadje). The two boys are soon scraping a living by acts of petty theft. Atim acquires his first cell phone. He also encounters Nassara for the first time and is troubled to find that he is a disabled war veteran and a baker with a young, pregnant wife, A cha (Aziza Hisseine) — and that he hands out free bread to the poor and street people every morning outside his bakery.

Atim comes back the next day, fingering his weapon beneath his clothes, but he hasn’t got the nerve to shoot Nassara. The latter notices him hanging back behind the knot of youngsters come for bread and asks him what he wants. “Not charity,” says Atim proudly.

“Well, if you’re looking for work, come back tomorrow.”

He does, and Nassara takes him on as an apprentice baker. Two or three other occasions on which Atim might take his revenge are allowed to pass, and soon the relationship between the two becomes like that between father and son. His own father had been killed before he was born — “Atim” means orphan — and his relationship with Nassara obviously fills a gap in his life. Moreover, he is proud to be learning a trade and scorns the invitation of Moussa to return to the life of the streets. On one occasion, Nassara is angered to the point of violence when he comes upon Atim and A cha laughing at him behind his back. Later he apologizes. “Sometimes I can’t control myself,” he says. “I can even be dangerous” — adding humbly, “I have done a lot of harm in my life.”

It’s a nice touch to have Nassara confirming Atim’s grandfather’s judgment of him, but in a context that utterly changes our understanding of its meaning. For he is also dangerous to the Abatcha family’s project of revenge by being so obviously decent and humane and penitent. A lot of the credit has to go to the immensely dignified and watchable performance of Mr Djaoro as Nassara. It is easy to see how Atim might be overawed by him, even without the personal relationship that has developed between them, and begin to get a bit of Western-style perspective on the primitive honor-culture’s demand for vengeance.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.