Making Much of Thomas Hardy’s Well-Beloved

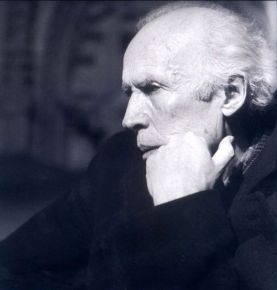

From The American ConservativeThomas Hardy

By Claire Tomalin

New York: Penguin, $35, 486 pp.

The Posthumous reputation of the English novelist and poet, Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), has continued to grow since his death almost 80 years ago. Nowadays, the author of Far from the Madding Crowd, The Return of the Native, Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure is in the popular view a bona fide Victorian G.O.M. (Grand Old Man) right up there with Dickens and Thackeray. Meanwhile, to the cognoscenti and literary criticis who still look down their noses a bit at the novels, he is known as the first great poet of the 20th century and, if the late Donald Davie is to be believed, the most influential of them all.

According to Claire Tomalin’s new biography, the central event in her subject’s life was the death of his first wife, the former Emma Gifford, in November of 1912. “This is the moment when Thomas Hardy became a great poet,” she writes. For, although he was 72 years old at the time and already celebrated throughout the English-speaking world as both a novelist and a poet, “it was the death of Emma that proved to be his best inspiration.” [xvii] This is not an observation that is original with her, but she is determined to make more of it than anyone else has ever done. As a result, her biography is really more of a couple than it is of a man — as were her earlier books on Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, Dora Jordan and King William IV and Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens.

The trouble is that she has so little to work with — except, of course, for the “Poems of 1912-13,” on which she has some interesting things to say. But the poems don’t have very much to tell us about the marriage, and the marriage has even less to tell us about the poems. Like most married couples of the Victorian era, Hardy and Emma did not talk or write about their marital relationship, even to intimates, and poor Miss Tomalin is reduced to picking up what she can from a stray remark or, often, what was not found in place where it might have been expected to be. Sometimes the strain begins to tell on her. Of Emma’s diary of their honeymoon trip to Paris, for instance, she writes: “Emma was a naive diarist, responsive to what she saw and fluent in a scatter-brained way. She makes you smile, sympathetically; and she shows her enjoyment of travel, but from our point of view she fails to seize her great opportunity — she might have been honeymooning with anyone, Hardy’s presence being barely mentioned.”

How inconsiderate of her not to have thought in the course of observing the manners and the appearance French people in the 1870s of the difficulties her reticence about her marriage would cause her husband’s biographer in the next century but one! Just look at what it makes her do when she comes to the point of having to describe the wedding:

If there was a celebratory lunch, if Emma looked beautiful with the soft, sunny light on her wedding dress, if she even wore a special dress, these things went unrecorded. Their happiness at being together at last after four and a half years of being in love and apart must be assumed. . .Whether both of them, having defied their parents, had regretful thoughts for them on the day, and whether lovemaking, at last licensed, was awkward for them, as for most newly married innocents, we shall never know, but there were many possible reasons for them to feel unsure of themselves. Yet they were doing what they had both dreamt of for four years and what he had worked for with unremitting dedication. Some sense of triumph and relief must have been in the air during their simple ceremony.”

Indeed! Her guesses on the matter are, presumably, at least as good as ours would be if it occurred to us to make any. But our heart goes out to her in her struggles with the mystery of the Hardys’ marital intimacy and quarrels. On the one hand, 1899 is mentioned as the time when Emma moved into her own bedroom into the attic at their home near Dorchester, Max Gate, but on the same page she tells us that this was also the date when the bicycle journeys she shared with “Tom” must have brought them closer together than ever. One long ride together in August of that year “suggests camaraderie and shared enjoyment, because it is difficult to keep up a quarrel or a sulk as you pedal along country roads.”

Or not. It’s pretty hard for her to make such stuff sound as if we’re learning very much about the great poet. The one thing we do know is that Emma was bitter about the fact that, when Hardy was writing Jude the Obscure (1895) he had sought the advice of his friend and admirer, the aristocratic Florence Henniker, rather than her own, regarding this as tantamount to the unfaithfulness that it seems he, but not Mrs Henniker, was prepared for. When the novel was attacked on publication as Jude the Obscene, it must have given her a certain satisfaction as well as, probably, a grievance for life. Soon she was observing that, in spite of what were regarded as her husband’s “advanced” views, his interest in her favorite cause of women’s suffrage “was ‘nil’ and that he cared only about the women he invented.” At any rate, it suited Hardy himself to believe that he had wronged his wife, though only after her death when her wrongs became the precondition of his falling in love with her again — and when she had become unobtainable. Such a romantic story! No wonder Miss Tomalin invests all her biographical capital in it.

It may even be true. But I would have preferred it if she had evinced just a bit of skepticism here — as she occasionally does elsewhere. At one point she mentions the scene in Jude in which we find the hero “looking through his straw hat as the sun shines through it and thinking, ‘If only he could prevent himself growing up! He did not want to be a man’” This is exactly Hardy’s own experience as a boy as described in Michael Millgate’s edition of Hardy’s own memoir, The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy, and she wonders at it. “The oddity is that he transposes the thought of a boy who had no conscious reason to be unhappy or to fear growing up into the mind of one who was already unhappy and had good reason to approach adult life with small enthusiasm. Hardy appears to be reinventing his childhood and making it worse.” Characteristically, she speculates about what specific sorrow might have caused this, but she acknowledges that “a retrospective blight cast across his life is a very Hardyesque possibility.”

Just so. Nothing odd about it, really. All his reimaginings of the human life he experienced seem to have made it worse. Why should we suppose that his marriage was any exception? That idea of the boy who doesn’t want to grow up sounds oddly up-to-date in our era of perpetual adolescence, and may not be unrelated to those “advanced” views of his in novels that an unkind reader might characterize as enshrinements of adolescent self-pity. This, after all, is the problem with Hardy’s novels, and Claire Tomalin wrestles with it as everyone must. “Critics,” she acknowledges, have been “disturbed” by them because Hardy “seemed to suggest that human beings might be brought down by malignant forces at work in the world, using their power to turn things to evil.” Now where might the critics have got an idea like that? Maybe from that famous moment at the end of Tess of the D’Urbervilles when, after the death of his heroine, Hardy commented that “‘Justice’ was done, and the President of the Immortals, in the Aeschylean phrase, had ended his sport with Tess.” To her credit, Miss Tomalin doesn’t buy Hardy’s own explanation of the line:

When he was attacked for it, he explained that ‘the forces opposed to the heroine were allegorized as a personality and that this was ‘not unusual in imaginative prose or poetry’. To suggest that readers should see that ‘the President of the Immortals’ is meant only to symbolize the forces of society that brought Tess down will not do as a defence. There is something more there, something that makes sport with her sufferings, and making sport with suffering is cruelty.

If there is, as I hope there is, just the hint here that Hardy, too, in his own way, is making sport of Tess’s sufferings, it is one of the few times that this biographer is prepared to level such a charge against the great poet. There should be more. She is even prepared to make apologies for the almost unbelievable letter of consolation that Hardy sent to his friend, the novelist H. Rider Haggard, on the death of his ten-year-old son, which expressed “sympathy with you both in your bereavement. Though, to be candid, I think the death of a child is never really to be regretted, when one reflects on what he has escaped.”

Here as in so many other places, we ought to be able to see that there was always something of the village atheist about Hardy, and a delight in shocking by his “free-thinking” ways. This game works better when there is not too much in the way of political radicalism or the more dangerous sorts of free-thinking that this biography and others occasionally fault him for avoiding. No, if you really want to shock people, keep up the normal appearances of life, go to your club and to church and vote Conservative, as Hardy did, while advertising your belief that “philosophers seem to start wrong; they cannot get away from a prepossession that the world must somehow have been made to be a comfortable place for man” — or that “this planet does not supply the materials for happiness to higher existences [meaning human beings]. . . Other planets may, though one can hardly see how.” The really remarkable thing is that such celebrity posturing as the great World-Sufferer should prove to be not inconsistent with the production of some truly great poetry. Now there’s a mystery that a biographer ought to be able to get her teeth into.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.