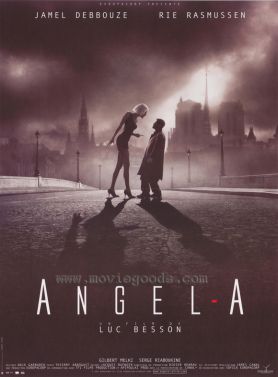

Angel-A

You might think that a movie in which It’s a Wonderful Life engages in a whirlwind romance with La Femme Nikita would be impossibly weird. But it turns out that the problem with Luc Besson’s Angel-A is that it’s not quite weird enough. Oh, the look of the thing could still be what Mr Besson’s fans have been waiting for. His first directorial outing since The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc (1999) and only his sixth since Nikita (1990), it is shot in black-and-white against the backdrop of a seemingly deserted and (therefore) other-worldly Paris. As in his earlier films, he has also made good use of really striking-looking actors. This time he has paired up the diminutive Jamel Debbouze (“Days of Glory”) with the Danish actress Rie Rasmussen (“Femme Fatale”) who, though only five feet ten inches tall, also wears sexy three-inch heels and towers over his five-feet-five.

Their appearance suits the relationship between a female angel — I almost wrote “agent” there, so reminiscent is Miss Rasmussen’s formidable powers of Anne Parillaud’s in Nikita — and her grubby little earthly client. The story starts as a straight lift from It’s a Wonderful Life. André, Mr Debbouze’s character, is deeply in debt to some very nasty characters and sees no way out but suicide. As he is about to jump into the Seine, he sees Miss Rasmussen’s Angela jump first and naturally jumps in to save her. “Angela — who’d be dead without me to save her,” he later reproaches her, before he is made aware of her supernatural provenance.

“André — who’d be dead without me to save,” she replies.

Except that, of course, she can’t die, as she reminds him when, even though he now knows she’s an angel, he tells her that smoking is bad for her. Smoking isn’t allowed where she comes from, she tells him, so she’s taking advantage of her “mission” to turn his life around to smoke all she can. It’s one of several indications that Mr Besson is seeking to overturn the conventions of the supernatural uplift picture. Heaven here is not the natural home of the soul but rather what Michael Bloomberg’s New York sometimes seems to aspire to be: an antiseptic place where everything that’s not forbidden is compulsory.

It may or may not be coincidental, then, that André improbably claims to be a New Yorker. True, he also tells us that he lies all the time, but his Brooklyn address is confirmed when he goes to the U.S. embassy in Paris for protection from his creditors — and is promptly thrown out on account of the criminal record that also shows up on the embassy’s computer.

“Powerful computer,” he observes philosophically.

Unlike Clarence, Frank Capra’s angel in Wonderful Life, Angela doesn’t attempt to show André the unwisdom of suicide by revealing what the world would be like without him. This angel is more out of the superheroes stable. Like Nikita she effortlessly whacks the bad guys; like Samantha the TV witch, she puts her unlimited power to conjure up goodies at the disposal of her little man. There is, however, a curious ambiguity about all this. Though she persuades André, with the help of some simple magic tricks that she says could get her “fired,” that she really is an angel, she also allows him to think she has provided him with the money he needs by the very non-magical expedient of prostituting herself. Nor is it quite clear, even when she later attempts to correct this impression, that she didn’t — for she, too, makes things up.

For example, she tells André two quite different and contradictory versions of the story of her previous life on earth, both unhappy. Bewildered, he asks: “Which was your life?”

“Which one makes yours more bearable?” she answers. “I can invent thousands.”

This turns out to be another reference to the oppressiveness of the cosmic utopia, where the angels are not allowed to know anything about their own past lives. Angela is supposed to teach André to face the truth about his life — and always to tell the truth to others — but she can’t face her own boredom with super-power, or her fear and resentment of the Tyrant upstairs. It’s an intriguing notion and feeds naturally into the more familiar trope of the god who would renounce his (or, in this case, her) immortality for the sake of human love. But though we may believe in the god, all right, it’s more difficult to believe in the love — which is too often mixed up with self-love.

For Angela’s version of the divine wisdom needed to haul André out of his pit of despair is so fraught with psychobabble about “self-esteem” that it spoils the impression the film elsewhere tries to create of the unattractive remoteness of the deity. Having been set up to reject this “wholly other,” Barthian God, we are shocked and a little disgusted to find His intervention in André’s life couched in terms of an empathy so soppy that it would make an advice-to-the-lovelorn columnist ashamed. What a pity that Luc Besson hasn’t quite got the courage of his own weirdness.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.