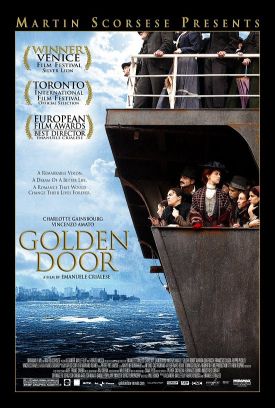

Golden Door (Nuovomondo)

There is an almost-magical moment in Emanuele Crialese’s Golden Door, whose Italian title is Nuovomondo or “New World.” On a ship full of mainly Italian immigrants to the United States some time during the first decade of the last century, a mysterious English lady named Lucy (Charlotte Gainsbourg) asks an illiterate Sicilian peasant named Salvatore (Vincenzo Amato) if he would marry her. We know nothing of her origins except that they must be (at least) middle class. She is educated and comparatively well-dressed, and she speaks Italian fluently. Yet she has no passport and travels alone and in steerage, along with the poor people. For reasons that are not quite clear, she thinks that attaching herself to Salvatore and his family (his mother, two brothers and two sisters) will help her to be accepted as an immigrant when the ship docks at Ellis Island. We have also been shown that she has another offer: to enter the country as the mistress of one of the rich men in first class. Instead, she chooses Salvatore, who has been smitten since the first moment he saw her. He naturally agrees at once to marry her.

“I’m not marrying you for love,” Lucy warns him.

Salvatore looks puzzled. “Love? We hardly know each other. These things take time, right?”

Somewhat hesitantly, Lucy replies, “Yes.” Salvatore then asks her for a lock of her hair. Once he has subjected it to certain spells or other treatments he has learned from his mother, known as a wise woman back home in Petralia Sottana, he will make her love him.

“I don’t believe in magic,” Lucy insists.

“With time, I will teach you,” he replies confidently.

Obviously, Mr Crialese thinks he can teach us too. His movie is shot through with the techniques of magic realism, though for the most part he keeps it closer to realism than to magic. I wish he had kept it closer still, for to my eye he doesn’t quite bring the magic off. Wisely, I think, he makes the magical element grow naturally out of the peasant superstitions that are everywhere in the Sicilian campagna where we spend the first third of the film. It begins with two men in bare feet climbing a rock-strewn mountain slope with stones in their mouths. They approach a cross erected on the mountain-top and deposit the stones alongside others, asking as they do for a sign that they should or should not emigrate. They then sit back to wait with complete confidence that a sign will be given.

I was immediately hooked. This is a film about the dream of a new world, but from our point of view it is the persuasive depiction of the old world that is strange, new and exciting. But I also have to say that there are some drawbacks. One is that the characters, though vividly realized, seem to inhabit only the world of the film and to answer to nothing in ours — which, I take it, the best movies of its kind would do. Part of the problem is that Lucy is given no backstory and hence no motivation for what seems some distinctly odd behavior. We are driven back upon the conclusion that she herself is a kind of magical apparition, perhaps the sign that Salvatore has asked for, since we have to accept that she is just the kind of thing that happens in the film’s world — not, that is, in the one we know.

This problem is only exacerbated by the magnetic presence of Miss Gainsbourg on the screen. That impossibly prognathous jaw set atop that improbably slender form makes her a true jolie laide and makes me, at any rate, unable to take my eyes off her. Moreover, Aurora Quattrocchi in the role of Salvatore’s mother, Fortunata, is almost her equal for charisma if not for sexiness. The two women between them represent the two poles of Salvatore’s existence: the past and the future, Sicily and America, the old and new worlds, yet so compelling are they in themselves that we are constantly tempted to forget any life beyond them.

This seems to be the effect Mr Crialese was trying for. We see nothing of America in the film except for the processing facilities at Ellis Island. The country remains as much our fantasy as it is the immigrants’, and the film takes advantage of the fact by introducing several fantastical interludes. In particular, one of the immigrants says that he has heard that there are in America rivers of milk. They have also seen joke postcards featuring giant vegetables. So we are treated to images of the characters bobbing about in not a river but a lake of milk, or of carrots that are as big as themselves. At this point, the peasant magic has gone where I can no longer follow.

But when Salvatore has himself boosted up beyond the frosted glass where he can catch a glimpse of the New York skyline and says he wouldn’t mind living in the sky; or when he has his first taste of white bread and thoughtfully observes that it is like eating a cloud — these are moments to treasure along with the prospective magic of the union of Lucy and Salvatore. At these moments, you will believe.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.