Getting it Right?

From The New CriterionHalberstam, Malcolm Browne, Neil Sheehan

“For those who remember journalism back in a 1970s heyday they can’t explain to to [sic] the young, [David] Halberstam’s death was not just the death of a hero, it was like the death of the great Hollywood stars — Katharine Hepburn, Clark Gable.” So wrote Henry Allen in The Washington Post shortly after the car crash which brought about the melancholy event to which he refers. He reminds us of what a paltry thing, in journalism’s little kingdom, is “just” the death of a hero — at least in comparison with the apotheosis of a celebrity. Halberstam, Hepburn, Gable. When did this trinity, rather than Washington, Lincoln, Roosevelt, or Eisenhower, Nimitz, MacArthur, become America’s great and paradigmatic figures before the world? The answer is at about the same time, back in the 1960s, when Halberstam was helping to revolutionize journalism. As Richard Holbrooke put it, “He made it not only possible but even romantic to write that your own side was misleading the public about how the war was going.”

It would be hard to overstate the many implications and ramifications of that revealing remark, quoted by George Packer in The New Yorker, by someone who is spoken of as a potential secretary of state in a future Democratic administration. To start with: if it’s now romantic to expose the falsehoods and hypocrisies of your own side, in what sense is that side any longer your own? Of course, journalistic piety would have it that the reporter doesn’t take sides but is just, in Mr Packer’s words, a “fearless truth-teller.” Yet in practice we know as well as Richard Holbrooke does that side matters. There are truths and there are truths. No one supposes that Halberstam could have become the equal of Hepburn and Gable by reporting on the misleading statements of the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese — always supposing he could have found any. It was because he was attacking, exposing, shaming what at the time would have been regarded, by the media culture as by everyone else, as his own side, that he became famous.

Moreover, the officials he attacked occupied, however unworthily, the place of those old-fashioned, “just”American heroes whom journalists in the past had been wont to treat so deferentially. There was obviously an immense feeling of liberation and empowerment for a young man who had come to feel entitled by his powers of intellect to look down on senior military officers — a feeling well captured by Ambassador Holbrooke in his account in The Washington Post of a memorable dinner in a Saigon restaurant in 1963 with Halberstam and Neil Sheehan:

They especially despised the senior commander, World War II veteran Paul D. Harkins, and after giving me some advice (“Don’t trust anything those bastards tell you”), David and Neil spent most of the evening denouncing Harkins. After some wine, they conducted a mock trial of the four-star general for incompetence and dereliction of duty. In his rumbling, powerful voice, David pronounced Harkins “guilty” of each charge, after which Neil loudly carried out the “sentence”: execution by imaginary firing squad against the back wall of the restaurant.

Such revolutionary high-spiritedness does not immediately suggest fearless truth-telling so much as it does the anarchic exuberance of youth presented with an opportunity for rebellion against what, at about the same time, we were learning to call “the Establishment.” That’s what made Halberstam a romantic figure at the time and since. He was a David who, looked at in the right light, had brought down the Goliath of the American military and political establishment with a well-aimed pebble. Thus it seems a bit disingenuous of Richard Holbrooke to celebrate the romance of his hero’s triumph while at the same time describing as “nonsense” the view that his reporting contributed to America’s humiliation in Vietnam by undermining support for the war at home. By calling him “romantic,” isn’t he implicitly giving him credit for just that?

There is also a paradox involved in the romance of exposing falsehood, for romance is itself a kind of falsehood. It may be a hopeful and a benign sort of falsehood, but it is still ineluctably false. By its very nature romance amounts to an exaggeration or glorification of what, looked at more closely, is at best mundane and at worst ugly or disreputable. Journalists, like novelists and film-makers, used to romanticize warfare by closing their eyes to much of the horror of it; now they romanticize the victims of war and so undermine war’s foundations by looking at nothing but its horrors. In the media’s reporting of war, honor and glory have become at least as invisible as the ghastly flow of blood and viscera once were to their predecessors. Nowadays, any journalist who wants to succeed knows he is in the business not of celebrating honor or trust or heroism but of exposing whatever sordid realities may be found (or invented) beneath the appearances of those things. And if the romantic prize is now awarded to those who tell tales of war’s evils, why should we not suppose that the supply of those evils will rise to meet the journalistic demand, just as the supply of heroes rose when the demand was for tales of heroism?

No fearless truth-teller that I know of has ever troubled to ask this question, let alone to answer it, for to do so would be to call into question the one unquestionable article of faith in the journalist’s credo, namely his own “objectivity.” Never mind the philosophical crudeness of this model of the media as a mirror in which realities are merely reflected. The transparency of the process, the neutrality of the observer in mediating for us the things he has observed must be insisted upon — barring occasional slips like the use of the word “romantic” above — at all costs if the journalist is to retain the authority he needs to be able to say with David Halberstam to the mighty of the earth: “You lie.” Without that authority, what hope of joining Halberstam in the Pantheon of celebrity along with Gable and Hepburn? Yet that objectivity and that authority are themselves lies whose foundational nature preserves them from scrutiny even when the part the media play in shaping events — see, for instance, “Biased Sensationalism” in the New Criterion of December, 2006 — or being manipulated by others to shape events is obvious to anyone without a stake in the pursuit of journalistic glory.

Halberstam’s old employer, The New York Times, took the occasion of his death to run a piece by Dexter Filkins, who writes for the paper from Iraq, comparing now with then. “During four years of war in Iraq, American reporters on the ground in Baghdad have often found themselves coming under criticism remarkably similar to that which Mr. Halberstam endured: those journalists in Baghdad, so said the Bush administration and its supporters, only reported the bad news. They were dupes of the insurgents. They were cowardly and unpatriotic.” Small wonder then that, before he died, Halberstam himself “did not hesitate to compare America’s predicament in Iraq to its defeat in Vietnam. And he was not afraid to admit that his views on Iraq had been influenced by his experience in the earlier war. ‘I just never thought it was going to work at all,’ Mr. Halberstam said of Iraq during a public appearance in New York in January.” Yet neither Halberstam nor Mr Filkins mentions one crucial difference between Vietnam and Iraq. In Vietnam, the enemy was militarily formidable even without any assistance from the media. In Iraq, the enemy is militarily weak and can only hope to win by exploiting the media’s negativity — and the continuing romance of their role in Vietnam — to make the war seem unwinnable. The role of fearless truth-teller is no longer available, if it ever was. Like it or not, the media are already involved in the action and must pick a side.

After noting how, since Halberstam, it has become part of the romance of being a reporter to question the bona fides of America’s leaders, Ambassador Holbrooke added: “But everything depended on David getting it right, and he did.” This strikes me as being equally revealing. “Getting it right” is of course an admirable ambition for a journalist, but it is an exercise that has little in common with what generals and politicians must do, which is to lead others through situations of mortal peril with appallingly incomplete and inaccurate information to guide them. Getting it wrong is a given. That’s what the romance of the Halberstamian example has made journalists — and not only journalists! — forget when they try to apply his lesson from Vietnam to the Iraq war. For the man who must act and not just observe, the only question that matters is how quickly he can recognize and recover from his mistakes and how strong is his will to keep fighting in spite of them and the inevitable setbacks they cause. On the first of these tests, the Bush administration has done rather badly, I think; on the second it has done rather well. But part of the reason for its failures has been that the mind of the media remains obsessed with the question only of its prescience — as if “getting it right” were the only thing that mattered and getting it wrong a fatal disqualification for leadership.

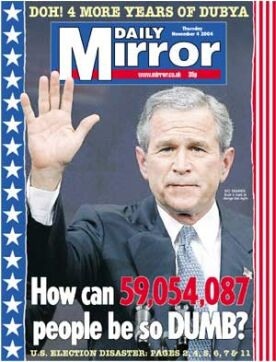

This odd prejudice may be partly owing to the huge social premium we put on intelligence in the era of the cognitive élite. People who have no idea on earth what to do about the war or any of the problems we face as a nation think it is some kind of program to ridicule the intelligence of the President. Even the political opposition has fallen into this trap by making mere perspicacity in the anticipation of evils rather than the determined effort to combat them its test of political success. Thus in Senator Jim Webb’s reply to the President’s State of the Union Address in January, he had no alternative to suggest to the measures for dealing with Iraq that had been proposed, but he was full of indignation on the grounds that the mistakes of the administration had been foreseeable. He knew that they were foreseeable because he himself had foreseen them. The implication was that he was much cleverer than President Bush — as if that was all that need be said to the credit of the former and the discredit of the latter.

The fact that the opposition and the media frame the debate in this way means that much of the administration’s energies have to be expended in defending itself against endless second guessing, which in turn means that it is even less inclined to recognize and correct mistakes. This is infantile politics. Meanwhile, on the question of what is now to be done about the mistakes, no one seems to know any better than Senator Webb, whose policy amounts to saying that we ought not to have made them in the first place. This is also the view of much of the Democratic party, and almost all of the media, who repeat mechanically that we need a “change of course” in Iraq but never get around to telling us what they would change — short of surrendering, which is now becoming the default option. In April, Senator Harry Reid finally bowed to the logic of his own position by acknowledging that the war was already lost. At any rate it had better be, if he wants to preserve the reputation for shrewdness and sagacity that he, like so many others, have cultivated by being wise after the event.

Events have a way of exposing bad information in ways that provide their chroniclers with endless temptations to such bogus wisdom. The chief of these is the temptation to say: “I know now, therefore they should have known then.” In this respect, Halberstam’s legacy to today’s Iraq war coverage — which was the subtext of so many of his posthumous tributes — has been not only to make yielding to this temptation OK for journalists — whose business of “getting it right” can always proceed at greater leisure and with fewer consequences for error — but to make it almost the whole business of journalism. This became apparent once again with the release of George Tenet’s memoir, At the Center of the Storm — a work which will long be remembered for its self-serving chutzpah and its ingratitude in a field that is far from short of examples of these qualities.

True, Mr Tenet could not quite get away with giving his book what is said to be the unwritten subtitle of all political memoirs, “If only they’d listened to me,” since all his problems had been caused by the fact that they had listened to him. True too, his attempts to blame others in the Bush administration for an intelligence screw-up that could clearly have been no one’s responsibility but his own did not extend to the President himself, who has paid an enormous political price for that screw-up and yet who has refused to kick the responsibility down the road to George Tenet, richly deserved though it is. Instead, this bungler was sent on his way to a prosperous retirement — the advance paid by HarperCollins for At the Center of the Storm is said to have been in the neighborhood of $4,000,000, a sum which cannot be unrelated to the prospect of the book’s giving yet another black eye to the President — with the Medal of Freedom. Yet what Mr Tenet does do is to cast away his own best defense — that, as William Goldman once said in another context, nobody really knows anything — in order to play the sterile journalistic game of who knew what, when, and who should have known it first.

In spite of its special pleading, the book does have at least one serious point to make. Although the former DCI’s claim to have been quoted out of context when he said that the existence of Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iraq was a “slam dunk” is laughable, he has a legitimate grievance when he says that whoever leaked his remark to Bob Woodward behaved very badly. “It’s the most despicable thing that ever happened to me,” he now says. “You don’t do this. You don’t throw somebody overboard. Is that honorable? It’s not honorable to me.” A bit late in the day, some might think, for someone who has spent as much time talking to Bob Woodward as Mr Tenet has to start complaining about what’s honorable and what isn’t when it comes to feeding the media’s scandal machine. Yet there should be more joy in heaven over the one sinner that repenteth than the ninety and nine (if you can find that many) who never strayed. Now we should all recognize, along with the Mr Tenet who found it out the hard way, that the media pursue their own interests in deciding what to report and how to report it and that, therefore, the picture we get from them is not a mere reflection of reality but something which, like David Halberstam’s reporting from Vietnam, helps to shape it, often in ways that are disastrous for everyone but the media — and, of course, America’s enemies.

My favorite recent example, which also went largely unnoticed as such, was the massive coverage the media afforded a murderous rampage by a mentally unbalanced youth at a university once known as Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, which now prefers to be known as “Virginia Tech.” The killer, whom I forbear to name for reasons that will soon become obvious, took a higher toll — 32 — than others of his kind, but he had in common with them the fact that he was a fantasist with a grandiose self-image founded on an obsessive interest in movie fantasy and an inexhaustible sense of grievance against the world. It seems to me at least arguable — to put it no higher — that such a person would not have done what he did without some idea that doing it would allow him to advertise his grievances while portraying his own death as some sort of glorious martyrdom.

What responsibility for the murders, therefore, and for more murders to come, lies with NBC, to whom the killer sent written and videotaped public statements about his rampage which NBC obligingly broadcast? “It was a tough call” for NBC, according to Bob Schieffer of CBS in a radio interview I chanced to listen to. Really? Funny, then, isn’t it, that it always gets called the same way — that is, for making such demented ramblings public instead of consigning them, unopened, unviewed and unread, to the incinerator. We have to try to understand why these things happen, the media cry. No we don’t! In fact, it’s the trying to understand that makes them happen. By telling a potential killer that he’s eligible for understanding, you confirm him in the belief that there are reasons for him to kill and therefore, to that extent, that it is all right to kill. The therapeutic approach, which the media find it convenient to adopt in these cases, essentially concedes the killer’s case that he is a martyr to whatever wrongs, imaginary or real, he sees himself as avenging. And, of course, his efforts at self-glorification depend on the media and their ability both to elicit such a response to his actions and, by doing so, to make him famous.

The importance of prospective fame as a motivator for those whose grievances against the world so often include their own obscurity and loneliness can hardly be overstated. It has been investigated by Albert Borowitz in Terrorism for Self-Glorification: The Herostratos Syndrome (Kent State University Press, 2005), which I have had occasion to mention before in this space (see “Honor Enduring” in The New Criterion of January, 2005). But the media’s effort to understand such killers as the Virginia Tech shooter must always stop short of understanding this. Writing in the British satirical magazine Private Eye, someone identified only as “Remote Controller” thought that “the thrill of getting ahead of the other networks on the biggest story of the year will have been undercut by a very mild unease that a guy who wished to be on TV after killing 32 people immediately identified NBC as a sort of al-Jazeera for psychopaths.” I wish I could believe this — that NBC suffered from even a mild sense of unease about its complicity in promoting a monster as a martyr. But I doubt it. The media’s treatment of the Iraq war suggests that the myth of the journalist’s independence from and lack of any responsibility for the events he reports on is now so firmly entrenched as to be quite immovable. For that we have to thank, at least partly, the romance of David Halberstam’s — and the media’s — Vietnam.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.