The Liberationist Myth

From The American SpectatorToo bad Jack Valenti was taken from us so soon after the massacre at Virginia Tech on April 16th had rekindled the debate over violence in the movies. His defense of the ratings system he devised back in the 1960s to take the place of the old Hays Code — now regarded, absurdly, as a form of censorship — might have served as a timely reminder of the extent to which that system was a product of its time and place. The liberationist mentality, still strongly characteristic of so many of those who, like me, came of age then, depended on a severing of the ties between individual behavior and its social consequences that had always, up until then, been taken for granted. This led to a similar dissociation between art and its effects on its audience, on the one hand, and the realities it represents on the other.

The reality principle has thus been banished from film as from the other arts. Utopianism, with its usual genius for reversing the meanings of words — compare “people’s democracies” — has ensured that when, today, someone says “in reality” what he means is “this is what I think.” Older readers may remember that it used to mean “what we can agree is the case, independently of any individual’s opinion.” Now there is no such agreement. Individual opinion is king. We are all reality entrepreneurs, manufacturing and producing private realities which we then attempt to market to others. One of many unfortunate consequences is that “It’s just a movie” has become the battle-cry — at once smug and despairing — of those who believe passionately that the abolition of reality was not too high a price to pay for the utopian dream of making each man absolute monarch of the fantasy kingdom inside his own head.

It is all a lie, of course, as utopianism always is — and as episodes like the shootings at Virginia Tech occasionally remind us. Or ought to remind us. So powerful is the liberationist myth, however, that the media echo chamber was swiftly filled with the sound of fantasy’s champions sharpening their swords for the satisfying work of hacking to pieces one or another of the straw men they always construct for themselves on these occasions. Here’s a fair sampling, from Sam Leith of the London Daily Telegraph:

The notion persists that there is a monkey-see, monkey-do relationship between violent or pornographic art and violent behaviour by its consumers, who — we’re told — are “desensitised” by it. This works both ways, incidentally. Censorship junkies believe art shapes societies in a simple way; as do totalitarians. The result — in Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany — was bad art rather than good citizens.

Speaking as a “censorship junkie,” I repudiate, along with the scare quotes around “desensitised,” both totalitarian ambitions and the belief that art shapes societies in a simple way. Art shapes societies in many ways, none of them simple — though they are no less obvious for that.

In Oldboy, for example, the Korean film that has been most often cited as having influenced the Virginia Tech shooter, there is not all that much violence, and very little of what there is involves gunplay. In the two most gruesome scenes, when a man pulls teeth with a claw hammer or, later, cuts off his own tongue with a pair of scissors, the camera cuts away after giving us only a taste of the gore. Neither “violence”nor its techniques is what the murderer could conceivably have learned from this movie. But neither can it be merely coincidental that it is an appeal to, and is itself positively drenched in, self-pity — which seems much more likely to have been instrumental in motivating a morose loner with a grudge against the world and a conceit of himself as some kind of artist to turn his violent fantasies into reality.

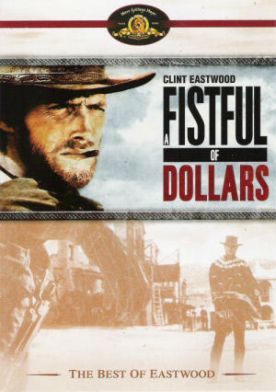

The pervasive self-pity of adolescent culture, and its flirtation with suicide, goes way beyond Mr Leith’s “monkey-see, monkey-do relationship” but it is no less influential for that. And it is only one of several aspects of that culture which, if there were any prosecutor in Virginia bold enough to put them in the dock, would have to plead nolo contendere. The other film that some have specified as a likely influence on the killer was John Woo’s Face/Off (1997), which may or may not have taught him how cool two-fisted gunplay looks — as was suggested in The Washington Post by Stephen Hunter whose own novel, Point of Impact, had just been filmed as Shooter. But there can scarcely be a doubt that Face/Off is the reductio ad absurdum of the moral-equivalence theory of violence that has reigned supreme in Hollywood since Clint Eastwood first took his six-shooter to Italy. Can’t anyone identify this de-moralization of violence, not in one film but in hundreds of them, as one of the killer’s accomplices?

|

If you go back today to re-view A Fistful of Dollars (1964), you are likely to be amazed at how little blood there is. Though the body count is unusually high, every time someone is shot he simply clutches his chest and falls over. The wound is almost never shown. This style was left-over from the old fashioned, moralistic Western that was interested in the rights and wrongs of violence, and had not yet discovered the purely aesthetic appeal of violent death. The only hint of what was so soon to come was the “graphic” scene in which Mr Eastwood gets caught and is savagely beaten up by the bad guys. Of course he’s a bad guy too. They’re all bad guys. That was the point, as it also had been in Akira Kurosawa’s original, Yojimbo, of 1961. Both Clint and Kurosawa’s hero, played by Toshiro Mifune, were just less bad than the rest: high-minded killers who were capable, at a given moment and almost on impulse, of acts of humanity or compassion which cost them dearly.

In Yojimbo, Mifune was also beaten up and thus started a trend — or continued one that was lifted from Hollywood noir pictures like The Glass Key (1942) or The Big Sleep (1946) — of the hero as spectacular sufferer, appealing not to our admiration or moral approval but to our pity. This, too, is part of the debasement and demoralization of the culture — which is what produces moral monsters and not, by themselves, the images of graphic violence that have become so common since 1964. Grindhouse by Quentin Tarantino, the high priest of fantastical and purely aesthetic violence, was released two weeks after Shooter and ten days before the Blacksburg rampage. It flopped, but the number one movie in the country the following weekend — and for weeks afterwards — was Disturbia, which features that Hollywood favorite, a serial killer (David Morse), who is so much taken for granted that the movie doesn’t even bother to give him any motivation. The ordinary guy-next-door who just likes killing people has become as much an American movie cliché as the cowboy or the gangster used to be.

Mr Leith’s animadversion upon us “censorship junkies” handsomely allows that “the work of art is involved in the violence” but, he adds, “it does not, as some people seem to think, ‘stand to reason’ that the relationship is a simple one of causation. Rather, the evidence suggests (given the number of consumers of violent art who don’t go on killing sprees) that the psychosis attaches itself to the artwork, rather than that the artwork causes the psychosis.” Once again he disingenuously pretends to believe that causation can only be “simple” when we know it’s not. What does “stand to reason” is that when suicide-chic is just one more lifestyle choice that the culture affords the morally and spiritually impoverished youths who have come hungry to its smorgasbord, or when they will have seen few or no examples of violence placed in the kind of moral context afforded by old-fashioned Westerns or other pre-ratings movies, there cannot be no connection between these facts and occasional outbursts of violence by certain of the more unstable sort of movie fans.

The problem is really with the concept of “violence” itself. Violence can’t be the problem. Popular culture has always been full of violence. The problem is one of contextless violence. For fifty years and upwards, the movies have been assiduously removing the moral context from the images of violence they deal in. From the samurai epics of the great Kurosawa to the lowliest shoot ‘em up the message is the same, and it is a message of moral equivalence. There are no good guys or bad guys but only those who suffer or those who inflict generic violence. Heroes may be cool but this isn’t at all the same thing as being good. Being good would be an embarrassment to the cool hero. Prowess in killing may still be admired, but that admiration is unlikely to extend to anyone who has a reason to kill beyond his own purposes of revenge, self-protection or self-enrichment. This reduction of violence to a matter of aesthetics must be what appeals to sick, self-obsessed kids. For them as for us, it is not “just a movie” but rather another re-affirmation of the liberationist principle that all art is or can be is self-justifying fantasy.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.