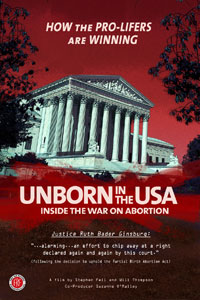

Unborn in the USA

Perhaps the most revealing as well as the most dramatic moment of Unborn in the USA comes near the end when an anonymous young woman confronts the Rev. Matt Trewhella. The director of an organization called “Missionaries to the Preborn,” Mr Trewhella travels the country with a group of supporters, many of them children, who hold up giant posters of aborted fetuses by the sides of busy highways. The young woman, who claims to be pro-life and a churchgoer herself, doesn’t like to have to see such things and tells him so. The Rev. Matt tells her that he’s glad she’s upset — that, in fact, it is what he was going for, since most people are simply indifferent to the fate of these poor innocents. Thereupon, the woman screams at him: “You’re creating indifference! You’re creating indifference by doing this!”

Unfortunately, he doesn’t have the wit to reply: “Yeah, I can see that now,” but the tragi-comedy of the moment is not lost. Subsequently, he either calls her a daughter of Satan or she thinks he does, and she assaults him on camera. There is a scuffle, and the police take her away in handcuffs. There is a similar kind of indirectness about the powerful emotions aroused on both sides of the abortion question — as if people can’t bear to acknowledge what’s really upsetting them. They look away from it as from Matt Trewhella’s gruesome posters. It is, therefore, much to the credit of the film-makers, Stephen Fell and Will Thompson, who began it as a student project when they were seniors at Rice University, that they manage for the most part to survey the landscape of confrontation between pro-life and pro-choice forces at its messier end without becoming emotional — or overt partisans — themselves.

Not that they don’t have a point of view. The film’s subtitle — “Inside the War on Abortion” — as well as its quotation right at the outset from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent from the Supreme Court’s decision upholding the ban on partial birth abortion makes their own pro-choice sympathies clear. But they know they can rely on the prejudices of a liberal audience — and, increasingly, the audience for all films apart from the most witless blockbusters can be assumed to be liberal — to supply the indignation at what, to the pro-lifers who are mostly unlikely to see it, would hardly raise an eyebrow.

For instance, the woman in Elmira, New York, who spends her life modeling in clay fetuses at all stages of development is likely to strike those of pro-life sympathies as poignantly devout, while pro-choicers may well see her as nuts. Likewise, the film’s journey inside the training program for pro-life activists at Focus on the Family’s headquarters in Colorado Springs can hardly avoid the whiff of left-wing conspiracy theory about the hidden potency of the dark forces of the right. There is also a bit of a Michael Moore moment when the film-makers’ absurdity-detectors zero in on a young man offering up a long prayer, during which he chokes himself up with his own compassion for the unborn, while chewing gum.

Mostly, however, Messrs Fell and Thompson eschew sardonic commentary or ridiculous subjects and allow the pro-life activists who are their main subject a fair opportunity to tell their own story in their own way. Only once do they step in to “correct” the views of a pro-life subject. When a woman claims from personal experience that there is “definitely a link between abortion and breast cancer” they hustle onto the screen a card informing us that the “overwhelming medical consensus” is that there is not. Do tell!

Yet I don’t quite like the built-in tendentiousness of the film’s interviews with a couple of apologists for violence against abortion clinics and doctors. True, these are balanced by a priest who says that such people are really more like the enemy: “They’re pro-choice,” he says, “because the pro-choice movement has been telling us for decades that sometimes it’s OK to end a life to solve a problem.” But the presence of such people in the documentary suggests — and is meant to suggest — a logical and moral continuum between the peaceful protesters and the killers. Perhaps bringing the latter into the argument is just the film-makers’ way of averting their gaze from some of abortion’s less savory moral implications.

The point in the end is the rather banal one that feelings run high on both sides. And, as the incident with the young woman and Mr Trewhella illustrates, feelings rather than dispassionate moral reasoning are inevitably what the documentary camera — like all cameras — seeks out. This may be fair enough, but the film ought to do more to try to sort out the honest feelings from the other kind. I wonder if it can be done?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.