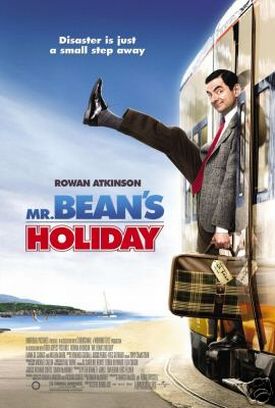

Mr Bean’s Holiday

Anyone who, like me, is an admirer of Mr Bean — the inspired, not-quite mute fuss-budget with the rubber face created by Rowan Atkinson back in the 1980s — should love Mr Bean’s Holiday. Directed by Steve Bendelack, whose career to date has been in British television, it offers a realistic context for Mr Atkinson’s visual comedy by sending Mr Bean from cold, rainy London to the south of France. As his knowledge of French consists of oui, non and gracias, the language barrier gives many semi-realistic opportunities for his mugging and miming and pratfalls. Just to complicate things further, linguistically speaking, Mr Bean finds himself through a characteristic series of mishaps in charge of a Russian boy, who speaks neither English nor French.

The movie then follows the pair of them as Mr Bean tries to make his way to his holiday destination in spite of one seemingly disastrous accident after another, as the boy tries to make it back to his parents in Cannes, and as the parents try to have Mr Bean apprehended for kidnapping. But this is also a movie about watching movies. Mr Bean’s touristy videocam becomes a key plot device and the source of much of the film’s visual humor. Yet what could have been a post-modern conceit, is kept mostly within the bounds of movie realism.

Not that Mr Bendelack is above giving us one or two po mo jokes. In one, Mr Bean is hitch-hiking along a country road for reasons that are much too complicated (and hilarious) to go into. He comes upon a wooden shack that might be a tool shed or an outhouse. It doesn’t matter what it is or what it’s doing there. We never find out. Mr Bean must get stuck in it and then, somehow, get out again. It is a kind of magic box and, therefore, like the magician’s audience, we can only view it from the outside and speculate on what Mr Bean may be doing in there. The first thing he is doing, we can be told. With a mighty heave, he shoulders the thing off its foundation. Now we have the much funnier sight of the shack moving back and forth, its unusual powers of locomotion invisible to us, by the side of the road and actually into the road.

Oh no! Can it be that the shack with Mr Bean in it is going to be flattened by that approaching tractor-trailer, which we identify by its air-horn off camera? Surely he will lurch out of its way? But for once the camera plays coy with us and will not allow us to see what happens as the shack wanders out of the frame. There is a crash, as of splintering wood, and Mr Bean, now shack-less, comes wandering back into the frame looking pleased with himself as he brushes pieces of wood out of his hair and clothes.

It’s a brilliant comic bit, but it also violates, post-modern style, the unwritten compact by which the viewer is led to expect that, however bizarre and zany Mr Bean’s adventures become — and they become very bizarre and zany indeed — they will not violate the canons of realism. Afterwards, the film goes back to being realistic with a smug grin on its face. There are two other occasions when a similar trick is performed and the otherwise almost exclusively visual humor gives way to a specifically non-visual gag in order to cover an apparently impossible event. The humor in each case is a thing of the moment and perceptibly off-center with the rest of the film. But if you’re willing to go with the po mo flow, it’s good for a laugh — partly at ourselves and partly at the film-makers, though not, in this case, at Mr Bean.

Yet it also reminds us, by its very difference from the rest of the picture, how very funny Mr Bean himself is when the camera plays it straight and lets him do what he does best. At two or three points, I was helpless with laughter — Mr Atkinson’s lip-synching to O Mio Babbino Caro from “Gianni Schicchi” is worth a particular mention — and always it was at stunts that might have been done on a stage and didn’t rely on any sort of “movie magic.”

In a way this is a joke at the expense of movie-makers, and the climax is precisely that. Willem Dafoe plays an annoyingly pretentious and self-absorbed director at a Cannes premiere which Mr Bean completely disrupts — in the process making his boring movie into something that wins rapturous applause. Like Mr Bean himself, Mr Bean’s Holiday is the movies’ revenge on those who make movies about themselves — which makes its final scene another po mo joke as the film-makers, like Mr Bean, in effect turn the videocam on themselves. You also might want to stick around through the end-credits for the coda that makes a similar point better than I can — and for Mr Bean’s third word of French, not counting gracias.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.