Gotta Get a Gimmick. . .

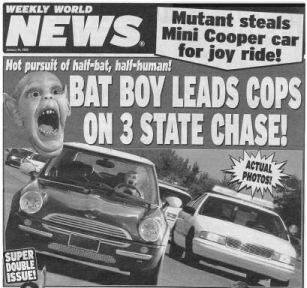

From The New CriterionSince The New Criterion’s last appearance, the summer has witnessed two epoch-making events in the storied history of American journalism: the acquisition by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation of Dow Jones, publishers of The Wall Street Journal, and the passing from the media scene of The Weekly World News, whose regular reports on Elvis- and alien-sightings and the continuing adventures of the mutant Bat Boy seem finally to have palled on a readership which once numbered over a million. Less earth-shaking but in its way, perhaps, more ground-breaking than either of these stories was the publication of Scott Gant’s We’re All Journalists Now which, in its title, provides the link between them and the occasion for some reflections on the relationship between news and entertainment.

In the first place, of course, the spate of viewing-with-alarm with which the rest of the media — and especially The New York Times — greeted the Journal’s sale was political in its motivations. Yet the Times’s editorial, under the heading “Notes About Competition,” claimed quite another sort of worry. Characteristically, it began with a bit of self-congratulation. “If we were in any other business, a risky takeover of a powerful competitor might lead to celebration,” wrote the preening editorialist. “Not in our business. Good journalism, which is an essential part of American democracy, thrives on competition. More than anything, competition makes our work better — more ambitious, more in-depth, more honest. When Americans are served by many different, responsible, competing news outlets, they can make more informed judgments. That is why we, and so many others, are paying such anxious attention to Rupert Murdoch’s purchase of Dow Jones & Company and its crown jewel, The Wall Street Journal.”

Oh, so it’s fears for the robust health of American journalism through not having strong competition for itself that The Times was worried about! Such gloriously unselfconscious bumptiousness would be hilarious if it were not so routine on the Times’s editorial page. The pretense of disinterested concern for competition and the editorial independence of a competitor was matched by the pretense of The Times’s own independence and freedom from the “slanted” news coverage it feared Mr Murdoch would foist upon The Journal. The Times reporter, Richard Pérez-Pe a, likewise noted that it was “troubling” to his journalistic colleagues there that Mr Murdoch “would like The Journal to be more of a counterweight to The New York Times, which he considers liberal.” Now where, do you suppose, could he have got an idea like that? David Ignatius wrote in The Washington Post that the decline of The Journal, for which he used to write, to the point where it was ripe for Mr Murdoch’s plucking, may have been in part owing to the conservatism of the paper’s editorial pages. “Advertisers, in the end, perhaps weren’t enthralled with a newspaper distinguished by vitriolic right-wing attack editorials.”

Perhaps! And perhaps, too, the advertisers didn’t mind so much the vitriolic left-wing attack editorials in The Times, where the paper’s “Media Equation” columnist, David Carr, went Mr Ignatius one better by writing that The Journal’s editorial pages were “known for a medieval brand of conservatism.” Now whatever else any friend or foe might call its “brand” of conservatism, which is free-market verging at times on libertarian, “medieval” is singularly inapt. What would medieval conservatism be, anyway? Royalist? Catholic? Who was more conservative in the modern sense, Guelph or Ghibbeline? That the modern idea of free trade and free markets was not even conceived of until the 18th century, let alone a matter for political debate, seems to be as unknown to Mr Carr as the meaning of the word “medieval,” which he must have learned from Ving Rhames’s threat in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction to “get medieval on your ass.”

The answer that The Journal’s own editorial gave to the professed concern of its competitors for its journalistic well-being was that “No sane businessman pays a premium of 67% over the market price for an asset he intends to ruin,” which would seem definitive. But there was also an element of resentment in all the anti-Murdoch manifestations against a broader offense to American journalistic Puritanism than just their subject’s conservatism, bad as that was in the media’s view. For the “competition” that The Times and others professed to be so anxious to preserve could be expected to be not just too conservative but too entertaining in the way that the British newspapers, among which the News Corporation’s Sun has long been the largest seller, have always been — or even as The Weekly World News was before its sad demise.

Mr Murdoch’s proprietorship of The New York Post has been marked by an attempt — not a terribly successful one, it should be added — to import to America something of the ethos of the British tabloids. This effort is at least as responsible as his politics — which are in any case far from being even as “medieval” as those of The Journal’s editorial page — for the suspicion with which he is regarded by The Times and others in the mainstream media. The Sun’s circulation, in a country with a population only a fifth of ours, is 50 per cent larger than that of the biggest-selling American newspaper, the unfailingly bland USA Today. The self-important American media, with their self-assigned role as truth-tellers to the powerful, are scandalized by such popularity. But I wonder if they can afford to be so much longer.

Not only in the tabloids but in Fleet Street generally there has never been the unbreachable barrier either between news and opinion or between news and entertainment that the American media flatter themselves by making into a shibboleth. This summer’s “silly season” in Britain has thrown up, among other delightful stories, a suppositious great white shark off the coast of Cornwall, a favorite destination for British holiday-makers, and the most recent sighting of the runaway earl, Lord Lucan, missing for 33 years but now found down and out and living in a Land Rover in Marton, New Zealand, with his pet opossum, Redfern. The Evening Standard (not a Murdoch-owned paper) got the scoop, and when it learned, prior to publication, that the man with the Land Rover and the opossum was not the missing lord but a younger and a shorter man called Roger Woodgate, it merely relegated the story from page one to page three. The story of the Earl’s not being found was a good one too, after all.

Good enough, indeed, to run in most of the other British papers, including the “qualities,” as well. Which would you rather read, The New York Times’s latest animadversions on Mr Murdoch’s alleged sins against the purity and high-mindedness of American journalism or a story about a man who is not Lord Lucan living in a Land Rover in New Zealand? The latter is not only more entertaining but more informative since, like that journalistic staple of yesteryear, the Loch Ness monster, it tells us something about the mythic resonances of the British popular culture in the same way that Bat Boy did with respect to America’s. When the latter’s creators at The Weekly World News started out in 1979, they tried to mix fact and fancy in their reporting, but they found themselves forced by the nature of the American media market to drop the factual altogether and become entirely fanciful.

This is still the case with The Onion, which some see as the successor to The Weekly World News. But The Onion is a free paper and so not quite on all fours with the WWN. People may still enjoy reading made-up news stories, but they’re less willing to pay for them. The quality of the fancy in the two papers is quite different too. The WWN’s reports on mutants and aliens were delivered with a straight face, and its signature opinion columnist, Ed Anger, told readers in his very name that they were to take the paper’s unseriousness seriously. And they did, too, a lot of them. Supposedly, when the paper reported that the FBI had captured Bat Boy, the FBI complained to the editor that its switchboard had been overwhelmed by calls from readers demanding that they set him free. The Onion, by contrast, delivers its fake news with a knowing, postmodern smile like that on the face of Jon Stewart, host of “The Daily Show” on Comedy Central.

Also as on that show, The Onion’s stories often come with a sly social and political commentary attached, though this is less predictably partisan than Mr Stewart’s are. My own recent favorite is “John Edwards Vows To End All Bad Things By 2011”

“Many bad things are not just bad — they’re terrible,” said a beaming Edwards, whose “Only the Good Things” proposal builds upon previous efforts to end poverty, outlaw startlingly loud noises, and offer tax breaks to those who smile frequently. “Other candidates have plans that would reduce some of the bad things, but I want all of them gone completely.” According to Edwards, his plan is composed of three steps. Everyday bad things, such as curse words and splinters, would be eradicated during his first six months in office. Next, very bad things, including child abduction, soil erosion, and resurgent diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, would be ended by the end of 2009. Finally, extremely bad things — plights such as genocide, species extinction, and virtually every form of cancer — would take a full two years to wipe out. “Racism will soon be a thing of the past,” Edwards said. “Same goes for being picked last for playground athletics, AIDS, robbery, not having enough spending money, and murder. Because these things are bad and not good, I promise they will be eliminated.”

Eulogizing The Weekly World News in The Washington Post, Peter Carlson purported to find the secret to the paper’s early success in the surreal quality of life in the 1980s and 1990s. “In their quest to make fake news seem real, WWN‘s writers found an unexpected ally — reality. The real news reported in real newspapers in those days frequently rivaled anything that WWN writers could concoct.” And, as examples, he mentions such amazing-but-true facts as these:

Americans elected a president who’d once co-starred in a movie with a chimpanzee. Rich women hired “surrogate mothers” to bear their children. The Soviet Union suddenly dropped dead. Scientists invented a magic pill that gave men erections. California cultists committed suicide, believing that the Hale-Bopp comet would carry them to heaven. Lurid details of a president’s sex life were released in an official government document. Religious fanatics hijacked airplanes and flew them into buildings. Arnold Schwarzenegger was elected governor of California. Scientists studying DNA revealed that humans were 98.6 percent genetically identical to chimpanzees. And on and on. Reality was getting so weird, it was tough for the folks at WWN to keep up. But they gave it their best shot.

But this is itself a sort of high-brow version of a WWN story: not true, but something that, for various reasons, its author wants to believe is true. Peter Carlson wants to believe it’s true for the same reason that Bat Boy’s fans wanted to believe he was true: because the falsehood flatters their sense of being in the know. Just as no one could know about Bat Boy without reading The Weekly World News, so no one could know of the weirdness of reality without sophisticated observers of reality like Mr Carlson to point it out to them. Otherwise, they’d just take reality for granted without ever knowing how unreal it really was.

That voice, the voice of the sophisticate, has become the characteristic note of the sort of American journalism — which sometimes seems as if it is virtually the whole of American journalism — that looks down its nose at Rupert Murdoch. It’s a voice that promises us a look behind the scenes at realities that are not otherwise accessible to us and that are masked by less interesting and invariably deceiving appearances. Anyone who knows how to put the voice on, and with just the right degree of sardonic superiority to the riff-raff who judge by appearances, is sure to ingratiate himself with the editors of The New Republic, to pick an example at random. That’s why that publication had the trouble it did a few years ago with Stephen Glass, whose smug and knowing tone in reporting on those that New Republic readers like to feel superior to served for a while as a sufficient cover for blatant fabrications. This summer it began to look as if TNR had again been duped by a Glass-like fabulist, the pseudonymous “Scott Thomas,” who was said to be a soldier serving in Iraq and who offered up pen-portraits of comrades-in-arms who were supposed to have behaved badly, or at least insensitively.

At the time of writing, The New Republic is still sticking by its claim to have corroborated all but one of the details in these reports by the man it has now named as Scott Thomas Beauchamp, the husband of one of the magazine’s junior staffers — though there were also unconfirmed reports that, in testifying under oath to an army inquiry into his allegations, Private Beauchamp had confessed to making everything up. But the truth or falsity of his stories seemed to me less important or interesting than their New Republic-style sneer of superiority to the men with whom he was serving. Moreover, as Charles Krauthammer pointed out in The Washington Post, the erroneous detail to which the magazine now confessed — that a particular incident in which soldiers in a mess hall had ridiculed a woman disfigured by a bomb had taken place in Kuwait, before he arrived in Iraq, and not in Iraq itself — really undermined the moral foundations of the ambitious meditations of “Scott Thomas” on war:

In the precious, highly self-conscious literary style of an aspiring writer trying out for a New Yorker gig, Beauchamp follows the terrible tale of his cruelty to the disfigured woman by asking, “Am I a monster?” And answering with satisfaction that the very fact that he could ask this question after (the reader has been led to believe) having been so hardened and brutalized by war shows that there is a kernel of humanity left in him. But, oh, how much was lost. In the past, you see, he was a sensitive soul with “compassion for those with disabilities.” In a particularly treacly passage, he tells us that he once worked in a summer camp with disabled children and in college helped a colleague with cerebral palsy. Then this delicate, compassionate youth is transformed into an unfeeling animal by war. Except that it is now revealed that the mess-hall incident happened before he even got to the war.

Whether the stories he told were true or not, the abbreviated literary career of “Scott Thomas” was as much entertainment for intellectuals, real or only aspirational, as Bat Boy was entertainment for the readers of The Weekly World News. Cleverness and literary sophistication are The New Republic’s big selling points just as amazing but little-known “facts” were those of the now defunct supermarket tabloid. I get the magazine’s (almost) daily e-mail of its own version of amazing political, economic or cultural facts and frequently marvel at how so many of its headlines offer us ever more enticing explanations of “why” or “how” something is or is not the case. This summer the come-on to an article by Jed Perl on classical art, for example, was “Why ancient art still has a claim on our attention” — something that, you’d have thought, anyone likely to want to read the article in the first place would already have figured out for himself.

This air of the over-eager explainer, the insufferable swot in the front row whose hand is always in the air, must appeal to some people, however irritating it is to those of us who are in the majority and who sit with the slackers at the back of the class and despise the teacher’s pet as much as we do an ambitious little snitch like “Scott Thomas.” It shows that The New Republic has at least found its niche in the new and increasingly crowded media marketplace, as more and more of us who are jostling for attention at the expense of nostalgic behemoths like The New York Times or the big broadcast networks will have to do. For if it is true that “We’re All Journalists Now,” we are less and less likely to be heard above the cacophony unless, like Mr Murdoch, we have some knack for entertaining as well as instructing.

Another of the summer’s sad events, according to The Washington Post, was the hospitalization of 83 year-old Faith Dane, the actress who played the stripper, Mazeppa, in the original, 1959 Broadway production of Gypsy. She suffered from pneumonia brought on, said her husband, by a refusal on the part of the producers of the musical’s new Broadway revival to hire her for the role she last played as a 36 year-old. Her star turn, you might remember, was to blow a trumpet between her legs and sing, along with two other splendidly turned-out “ecdysiasts,” the memorable ditty, “You Gotta Get A Gimmick.” So it is, increasingly, in the news business. Mr Murdoch has got a gimmick; The New Republic has got one, too, however unattractive it is to some of us. But I wonder if The New York Times’s style of solemn omniscience and journalistic and political rectitude really qualifies? One can imagine a new-media future in which these qualities begin to look as out-of-date as The Weekly World News.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.