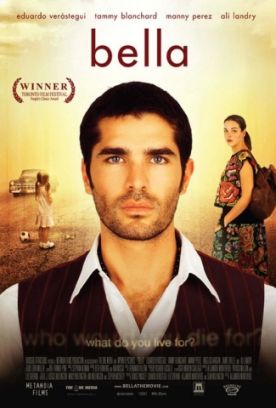

Bella

“I can’t even take care of myself; how am I going to take care of a kid?” says the beautiful Nina (Tammy Blanchard) to Jesus-like — or perhaps more Joseph-like — José (Eduardo Verástegui) in Bella, by the Mexican-American director, Alejandro Gomez Monteverde. It’s a story as familiar as the continuing saga of Britney Spears, except that Britney never thought to use her own incompetence as an excuse for aborting her children. Nina, who does think of it, has none of Britney’s craziness. There is no obvious substance abuse or bad driving. We can’t imagine her shaving her head. At worst she seems a bit disorganized and has a problem with punctuality which gets her fired from her job as a waitress at the restaurant run by José’s hard-charging brother, Manny (Manny Perez). José, who works there as head chef, decides on the spur of the moment to take the day off to find out what’s wrong in her life.

The answer is not quite enough, unfortunately. We learn that she’s pregnant and disinclined to keep the child, partly because her own childhood was an unhappy one. Her mother had gone into an emotional tailspin after her father’s death. “I raised myself — and her,” she tells José. It’s reason enough, perhaps, for her not to want children of her own, but how, then, are we supposed to believe that she’s unable to look after a child? She might have other problems, but we never find out what they are. Her refusal even to consider marrying the anonymous father of her unborn child, in particular, suggests a personal disorder that the film doesn’t care to explore. Why has she been sleeping with a man she doesn’t love, or even like?

The reticence of Mr Monteverde and his fellow screenwriters, Patrick Million and Leo Severino, on these questions is a pity, since it means that everything we see of Nina shows her as being much too pulled together, competent and attractive for someone who is supposed to be so helpless and unable to cope. We may get the feeling that we’re being protected from the sight of what would otherwise look like the cold, calculating ruthlessness with which Nina decides to “take care of” her pregnancy when, for obvious reasons, it is important for the film not to allow us to lose sympathy for her.

The reason for this moral continuity error will soon become equally obvious. It is that Bella, though a charming and even moving film at times, is propaganda — superior and well-made propaganda, to be sure, and with a message that I happen to agree with, but still propaganda. As such, it has the limitations of the form, the chief of which are that the characters tend to the emblematic and don’t look quite real and that we’re aware from the start that the deck has been stacked and the dramatic conflict has to come out the way it does.

That having been said, Mr Monteverde does a good job of keeping our interest. The first we see of José, he is at the beach closely observing a little girl as she plays in the surf. Is he, perhaps a pervert? Then we flash back to a time some years previous to the main action when José, minus his Jesus-beard, is a soccer star and hero of the Hispanic streets. He is about to sign a big contract to play professionally and is apparently without a care in the world. A sense of foreboding hangs over his kicking a ball around with some boys in the street, taking their ball to get it autographed by the team he is about to join, and then getting in the car with his manager to sign the contract.

We’re not quite sure, yet, how he will make the transition from this rich, famous, stylish athlete and sex-symbol to the brooding, bearded figure behind the stove in his brother’s restaurant, but the sense of doomed youth hangs over the film from the opening voiceover at the beach: “My grandmother always said if you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans.” In other words, he, like Nina, experiences a plan-changing — and life-changing — event, though we’re not told what it is until near the end. Likewise, José’s tense relationship with Manny, who is furious with him for walking out just as the lunch crowd is about to arrive, conceals a family secret that will only be revealed gradually, though opportunely, as José takes Nina from the city to Long Island to meet the rest of his family.

Like José and Nina, José’s mother (Angélica Aragón), father (Jaime Tirelli), brother Eduardo (Ramon Rodriguez) and other family members are too attractive to be quite real. Their job is to stand for the joys of family life that Nina, intent on her abortion, has never really known. Such relentless life-affirmation extends even to a blind beggar they meet on the way with a sign saying: “God closed my eyes; now I can see.” Clearly, it would take a woman much more stony-hearted than Nina to hold out against all this. I don’t want to be too hard on a movie that I did enjoy and that preaches what I, too, believe. The Sunday-school lesson is right, true and much-needed, but it’s still, alas, a Sunday-school lesson.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.