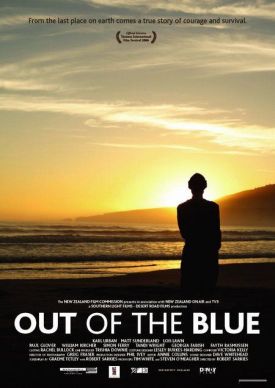

Out of the Blue

“From the last place on earth comes a true story of courage and survival.” Though the tagline for Robert Sarkies’s Out of the Blue focuses on the positive, it’s also a story of madness, cowardice and death. But it turns out that the salient detail is the one about “the last place on earth.” It’s not a bad way to describe the southeastern part of the South Island of New Zealand where wild and beautiful landscapes, shared by the sparse human population with penguins and seals, remind you that the next stop is Antarctica. But what has the location to do with this tragic story of a nut-case and his semi-automatic rifle? You’d think America would have plenty of crazed-gunmen stories of her own to tell, without having to import them from pacific New Zealand.

Mr Sarkies’s camera does its best, however, to persuade us that the murderous rampage David Gray (Matthew Sunderland) went on in Aramoana, New Zealand, in November of 1990 was somehow connected with the place where it happened. For a movie containing so much sickening violence, this one has an almost idyllic appearance and pace. Often, the camera cuts away from its narrative duties to shots of the stark and beautiful New Zealand coast-line — sometimes in static aerial shots which seem intended to give us the impression of looking down on the human tragedy from an immense, god-like height, like that of the persona Keats imagines for himself, even as he rejects it, in his sonnet on the “Bright Star” —

. . .watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like Nature’s patient sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores. . .

It’s an interesting idea, thus to supply a purely cinematic and passionless perspective on such emotionally harrowing material. Is it meant to echo a moral perspective, or to take its place?

The title provides the clue. Like most artists these days, Mr Sarkies regards violence as being practically an act of God. There is no accounting for it. It can simply be taken for granted. The question of how David Gray came to the point of gunning down thirteen of his neighbors doesn’t really interest him, therefore. If it hadn’t been Gray murdering people for no reason, it would have been somebody else.

Of course, some viewers may regard Gray’s murders as not being “out of the blue” at all. According to the normal conventions of film-making, he is an obvious killer from the start: a loner and a gun-nut with an anger problem and more than a hint of paranoia about him. If his neighbors had seen him in a movie, as we do, they’d have known what was coming long in advance. But that’s just it. When you’ve lived all your life next door to, or down the street from the guy, you don’t see him the way a movie audience would. When things have been the way they are for a long time, or have only gradually become that way, it’s hard to understand how everything can change in an instant.

The great virtue of Mr Sarkies’s film is that he sticks very closely to what must have been the actual point of view of the people caught up in the shooting rampage. The sickening fear of knowing that there is a crazy man nearby who is shooting people at random but not knowing where he is, of seeing badly wounded people lying out in the open but not being able to go to their assistance without becoming a target yourself — these things are well-conveyed. That empathetic approach extends even to the gunman himself. If evil is something that comes “out of the blue” and not as a result of rationally explainable moral choices, then Gray must be as much its victim as those he kills. The last we see of him here is meant to make just that point.

Likewise, the policeman (Karl Urban) who has him in his sights and can’t bring himself to pull the trigger is meant to be seen as merely the victim of his own compassion and decency, not a fool and a coward whose hesitation must have cost several lives. The film makes no moral judgments, here or anywhere else, instead preferring to enjoy the artistic prerogative of creating a tableau of tragedy and victimhood which can be appreciated aesthetically and emotionally. To me, that is a serious limitation, an abdication of moral responsibility. But those who are less particular about such things may find much to like about the movie — especially its sharply-observed, often comic portraits of the Aramoanans, who are seen as a sort of kinder, gentler version of American rednecks.

Deserving of special mention is the grandmotherly Mrs Helen Dickson (Lois Lawn) who’s just had her hips “done” and can barely walk, but who crawls and drags herself back and forth between her house and a badly wounded man in the road outside it in an effort to bring help. She serves as a welcome reminder that not even the most determined efforts of the aesthete and the non-judgmental but still god-like observer can quite deny us a hero — any more than they can altogether deny us a villain. For I suspect that most viewers will be somewhat less inclined than Mr Sarkies appears to be towards regarding this murderer of women and children as an object of pity.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.