Right Wing Fantasy

From The American SpectatorTall, and tan, and young, and lovely

The girl from Ipanema goes walking

And when she passes, I smile — but she doesn’t see. . .

Well, duh! But Antonio Carlos Jobim wasn’t really as dumb as he sounded. He was just giving expression to an eternal masculine longing: not for the tall and tan and young and lovely girl from Ipanema. That’s a given. Duh, again. What he really wants is for the girl who looks straight ahead, not at me (nor at any of the others who are going ah. . .) instead to look at him the way he looks at her. Yeah, like that’s going to happen! In effect, he wants her not to know that she’s tall and tan and young and lovely, or that this gives her the sort of power over men that it always has and always will. Ooh, but I watch her so sadly, he sings, but it’s not because he loves her. It’s because he wants the sex of the eye, sex without complications. He wants her to feel the pure lust her body excites in him, and he’s sad because he knows she never will.

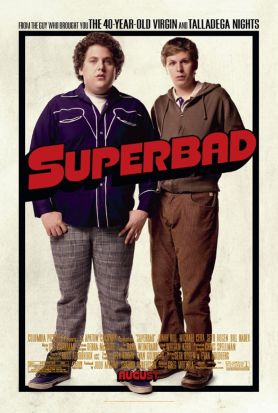

Even when we know this, even when we understand perfectly well how the sexual economy works and that sex never comes without complications, we men still can’t resist that fantasy, which also lies at the foundation of all pornography. It’s the fantasy of the attractive woman who doesn’t want anything but what we want — and who, therefore, doesn’t know about or care to use the power her attractiveness gives her over us but only to enjoy the sex for its own sake, the way we do. In Greg Mottola’s smash hit movie, Superbad, written by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, Mr Goldberg’s teenage alter ego, played by Michael Cera, puts it this way: “Imagine if girls weren’t weirded out by our boners but wanted to see them. That’s the world I want to live in some day.”

I particularly liked that formulation, because it seemed to have been put in to show that the film’s randy and raunchy high school kids actually recognize for what it is the sexual utopianism that they otherwise find so irresistible. It’s even a satirically feminist point, since it represents a corollary of the feminist brand of sexual utopianism. Yes! We want to be equals! Please treat us as sex-objects too! Unfortunately, this temporary detachment from the urgency of their own desires fades as Mr Cera and his foul-mouthed sidekick, played by Jonah Hill, embark on a madcap project to win the sexual attentions of two pretty classmates (Martha MacIsaac and Emma Stone, respectively) — by providing the booze for a party they’re giving — that actually succeeds.

That these girls would lust for those boys and then act upon their feelings is not completely impossible, I suppose, but anyone who’s ever been a teenage boy would have to acknowledge the fantastical element in such a scenario. And the movie goes in for some even more energetic — and funnier — fantasizing by showing us a couple of fun-loving cops, played by Mr Rogen and Bill Hader, who take under their wing a kid seemingly afflicted with terminal nerdishness (Christopher Mintz-Plasse) and obligingly make him over into the coolest guy in the class.

I wouldn’t even bother to mention it — news flash, Hollywood produces sex fantasy! — but that, to hear some of its more enthusiastic apologists, you’d think Superbad was an epoch-making film, the Citizen Kane of high school sex comedies. Manohla Dargis of The New York Times gives the credit to Judd Apatow, who produced Superbad and directed The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up, saying that “part of what’s fascinating about Mr. Apatow’s ascendancy, and why the comedy moment belongs to him more than it does either to the Farrelly brothers or to Ben Stiller and his mob, is how he has created — and come close to perfecting — a masculine variation on aspirational wish-fulfillment movies like Legally Blonde. Except instead of perky, pretty women reaching up, up, up, Mr. Apatow offers freaks and geeks aching to be worthy of those same women.”

Well, that’s one way of putting it, I suppose. But, having been a teenage boy myself, I think what they’re aching for is the same thing that Antonio Carlos Jobim was aching for, the thing that can never be. They, too, want the girls they lust after to lust after them. And, lo, they do! It’s as if the Girl from Ipanema had turned to Antonio Carlos and said, with a wink, “What about it, then?” Except that in that case there would never have been a song about her. There’s a similarly vanishing quality to Superbad. “Ooh, I’m so wet right now,” purrs Becca (Miss MacIsaac) to Mr Cera’s Evan as, deliciously lubriciously, she climbs all over him.

“Yeah, they said that would happen in health class,” he says.

It’s a wonderful joke, but it only really works in the context of unreality that the film has set up around it. Its piquant combination of sweet innocence and frankly obscene lustfulness is not untrue to the experience of adolescence, but this is because adolescents perforce live in a fantasy world when it comes to the adult things, like sex, that they are not yet ready for. And if they experience those things prematurely, they tend to bring their fantasy worlds with them. I don’t think it is coincidental that, as I noticed in this space last month, fantasy is now also the normal language of the movies. The anarchy of the adolescent imagination, instead of being something to be disciplined, is now something to be celebrated and enjoyed, by adults as much as children.

In this sense Superbad really is epoch-making. Now, it tells us, it is “right-wing” (Mr Rogen’s description of his movies) to be shameless. Knocked Up, which opened earlier in the summer and in which Mr Rogen stars, is perhaps “right-wing,” as these things are measured nowadays, in the sense that a very inconvenient pregnancy is not allowed to be terminated, but I think he means more than this. For in a way shamelessness is right-wing — instead of being, as it used to be, left wing. If frankness about male lust is stigmatized not as an offense against chivalry or good manners or moral hygiene but against political correctness, then the new libertarian and politically incorrect “right-wing” can be expected to take up frankness about male lust as its own cause, and to use it as a weapon against feminist fantasies.

There’s a certain attractiveness to this idea, but it depends on our closing our eyes to the fact that, as Antonio Carlos Jobim showed all those years ago, male lust is every bit as fantastical, in its way, as feminist utopianism. The two fantasies meet at the point where Superbad’s Evan longs to be treated as a sex object. What’s missing in all this fantasizing, the old-fashioned right wing would have pointed out, is what the literary theorists of the left would call transgressiveness. Society sets up boundaries for us — at least it used to — with regard to sex, and it is the transgression of those boundaries, as much as the sex itself, which appeals to our interest and gives us a thrill. Paradoxically, real sex becomes less real, and less interesting, when those boundaries have been abolished.

So, of course, do movies. Superbad has to try so hard to be filthy in order to give us back just a faint memory of that frisson of naughtiness which, in Cole Porter’s olden days, was created by a glimpse of stocking. The shocking truth now is that the reality of sex lies not just in the delightful collision of bodies but includes the social context that fantasy always wants to leave out. There is a similar point to be made about violence, and I was shocked to find A.O. Scott — not a critic with whom I very often find myself in agreement — making it in The New York Times. A propos of the 40th anniversary of Bonnie and Clyde, he wrote that “Even the most bloodthirsty moviegoer would be likely to leave a real fusillade like the one at the end of Bonnie and Clyde sickened and traumatized, rather than thrilled. The particular charge of that scene, and others like it, is that it tries to push the pretense — the art — as close to trauma as possible and to make the appreciation of that art its point. Missing the point is what marks you as square.”

Not to put words in Mr Scott’s mouth, but I think he means that being “square” in this sense, at least as an intellectual stratagem for understanding certain kinds of art, is a good thing. It means that you retain a healthy appreciation of the difference between art and life which gives you a point of perspective not only on movie violence like that in Bonnie and Clyde but on the whole all-is-permitted world of postmodern fantasy designed to make us forget that there is such a difference — or, indeed, that “life” exists at all apart from the art with which we represent it to ourselves and others. I hope that, beneath their extreme coolness, Messrs Apatow and Rogen are square enough, and right-wing enough, to understand this.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.